Through dozens of letters and several face-to-face meetings, the two forged a friendship that lasted until Frank died in 1980 at the age of 91.

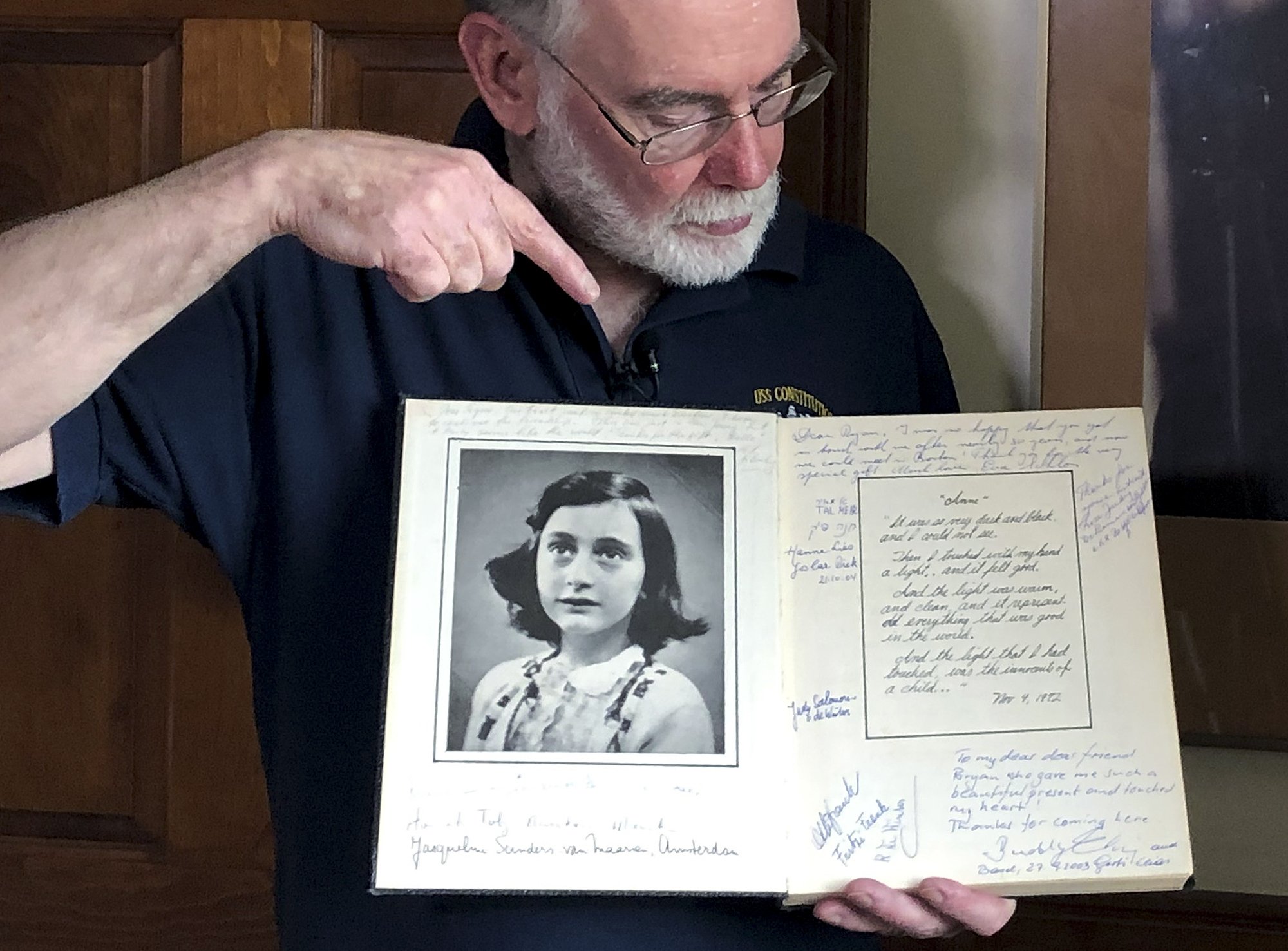

Now 73 years old, Cooper, an antiques dealer and artist in Massachusetts, has donated a trove of letters and mementos he received from Frank to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington ahead of the 90th anniversary Wednesday of Anne Frank's birth on June 12, 1929.

He wants the letters to be shared so that people can have a deeper understanding of the man who introduced the world to Anne Frank, whose famous World War II diary is considered one of the most important works of the 20th century.

"He was a lot like Anne in that he was an optimist," Cooper said of Otto Frank at his house on Cape Cod recently. "He always believed the world would be right in the end, and he based that hope on the young people."

As the German army occupied the Netherlands, the Franks hid in the attic of Otto Frank's office in Amsterdam. But they were eventually discovered and sent to concentration camps, where 15-year-old Anne, her elder sister and her mother died -- among an estimated 6 million Jews killed by the Nazis.

Otto Frank was the only family member to survive, living to see the Soviet army liberate the notorious Auschwitz camp in Nazi-occupied Poland in 1945. He had his daughter's diary published two years later and dedicated his days to speaking about the atrocities of the Holocaust.

But in his letters and conversations in person, Frank focused less on his family's ordeal and chose instead to counsel Cooper through his own everyday struggles. For Cooper, those ranged from losing his mother, to questioning his Jehovah's Witness upbringing to worrying about his career and romantic relationships.

"Some of the letters really have nothing to do with Anne," Cooper said. "In a lot of ways, I feel like I was adopted by Otto. He made me feel like I had a family during a period of real isolation."

In one letter, Frank urged Cooper to draw inspiration from Anne's optimism under vastly more dire circumstances.

"I want to remind you of her ardent wish 'to work for mankind' in case she would survive," Frank wrote on Jan. 9, 1972. "I can see from your letter that you are an intelligent person and that you have self criticism and so I can only hope that Anne will inspire you to find a positive outlook on life."

The letters also show the toll Otto Frank's life work had on his physical and mental health, said Edna Friedberg, a historian at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

In one of the later letters to Cooper, Frank's second wife, Elfriede "Fritzi" Frank, wrote about how her husband struggled to maintain his health during a series of public appearances and interviews ahead of the 50th anniversary of Anne Frank's birth.

"You can surely imagine that all this is very emotional for him and takes a lot of his strength," she wrote on March 21, 1979. "But you cannot prevent him for doing what he thinks is his duty."

Otto Frank died the following summer.

As Anne Frank's 90th birthday approaches, Friedberg said it's important to remember the sacrifices Otto and others made to keep her legacy alive. Her writings were preserved by Miep Gies, Otto Frank's secretary who helped the family while they were in hiding. She returned the documents to him after the war.

"Otto Frank never had to publish that diary. As a parent in mourning, he could have kept this to himself," she said. "But he gave it as a gift to humanity because he saw that it spoke to something bigger. He took that charge and ran with it for the rest of his life."

The museum will digitize and eventually make Cooper's collection available online. It totals more than 80 letters, including his correspondence with Gies and others who aided the Frank family during the war, and a number of modest family keepsakes. Those include Otto Frank's coin purse and a photo of Anne.