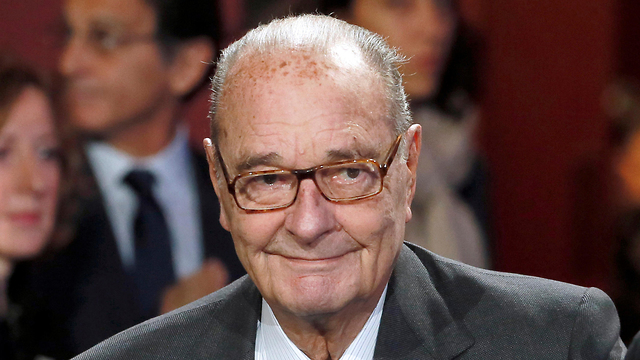

Jacques Chirac with Shimon Peres

Photo: AFP

Jacques Chirac, a two-term French president who was the first leader to acknowledge France’s role in the Holocaust and defiantly opposed the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, died Thursday at age 86.

His son-in-law Frederic Salat-Baroux told The Associated Press that Chirac died “peacefully, among his loved ones.” He did not give a cause of death, though Chirac had had repeated health problems since leaving office in 2007.

His death was announced to lawmakers sitting in France’s National Assembly, and members held a minute of silence. Mourners brought flowers and police set up barricades around his Paris residence, as French people looked past Chirac’s flaws to share grief and fond memories of his presidency.

Chirac was long the standard-bearer of France’s conservative right, and mayor of Paris for nearly two decades. He was nicknamed “Le Bulldozer” early in his career for his determination and ambition. As president from 1995-2007 he was a consummate global diplomat but failed to reform the economy or defuse tensions between police and minority youths that exploded into riots across France in 2005.

Yet Chirac showed courage and statesmanship during his presidency.

In what may have been his finest hour, France’s last leader with memories of World War II crushed the myth of his nation’s innocence in the persecution of Jews and their deportation during the Holocaust when he acknowledged France’s part.

“Yes, the criminal folly of the occupiers was seconded by the French, by the French state,” he said on July 16, 1995. “France, the land of the Enlightenment and human rights ... delivered those it protects to their executioners.”

With words less grand, the man who embraced European unity — once calling it an “art” — raged at the French ahead of their “no” vote in a 2005 referendum on the European constitution meant to fortify the EU. “If you want to shoot yourself in the foot, do it, but after don’t complain,” he said. “It’s stupid, I’m telling you.” He was personally and politically humiliated by the defeat.

His popularity didn’t fully recover until after he left office in 2007, handing power to protege-turned-rival Nicolas Sarkozy.

Chirac ultimately became one of the French’s favorite political figures, often praised for his down-to-earth human touch rather than his political achievements.

In his 40 years in public life, Chirac was derided by critics as opportunistic and impulsive. But as president, he embodied the fierce independence so treasured in France: He championed the United Nations and multipolarism as a counterweight to U.S. global dominance, and defended agricultural subsidies over protests by the European Union.

Chirac was also remembered for another trait valued by the French: style.

Tall, dapper and charming, Chirac was a well-bred bon vivant who openly enjoyed the trappings of power: luxury trips abroad and life in a government-owned palace. His slicked-back hair and ski-slope nose were favorites of political cartoonists.

Yet he retained a common touch that worked wonders on the campaign trail, exuding warmth when kissing babies and enthusiasm when farmers — a key constituency — displayed their tractors. His preferences were for western movies and beer — and “tete de veau,” calf’s head.

After two failed attempts, Chirac won the presidency in 1995, ending 14 years of Socialist rule. But his government quickly fell out of favor and parliamentary elections in 1997 forced him to share power with Socialist Prime Minister Lionel Jospin.

The pendulum swung the other way during Chirac’s re-election bid in 2002, when far-right leader Jean-Marie Le Pen took a surprise second place behind Chirac in first-round voting. In a rare show of unity, the moderate right and the left united behind Chirac, and he crushed le Pen with 82 percent of the vote in the runoff.

“By thwarting extremism, the French have just confirmed, reaffirmed with force, their attachment to a democratic tradition, liberty and engagement in Europe,” Chirac enthused at his second inauguration.

Later that year, an extreme right militant shot at Chirac — and missed — during a Bastille Day parade in 2002. Inspecting troops, the president was unaware of the drama.

While he had won a convincing mandate for his anti-crime, pro-Europe agenda at home, Chirac’s outspoken opposition to the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 rocked relations with France’s top ally, and the clash weakened the Atlantic alliance.

Angry Americans poured Bordeaux wine into the gutter and restaurants renamed French fries “freedom fries” in retaliation.

The United States invaded anyway, yet Chirac gained international support from other war critics.

Troubles over Iraq aside, Chirac was often seen as the consummate diplomat. He cultivated ties with leaders across the Middle East and Africa. He was the first head of state to meet with U.S. President George W. Bush after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Chirac was greeted by adulating crowds on a 2003 trip to Algeria, where he once battled Algerians fighting for independence from France.

At home, myriad scandals dogged Chirac, including allegations of misuse of funds and kickbacks during his time as Paris mayor.

He was formally charged in 2007 after he left office as president, losing immunity from prosecution. In 2011, he was found guilty of misuse of public money, breach of trust and illegal conflict of interest and given a two-year suspended jail sentence.

He did not attend the trial. His lawyers explained he was suffering severe memory lapses, possibly related to a stroke. While still president in 2005, Chirac suffered a stroke that put him in the hospital for a week. He had a pacemaker inserted in 2008.

Jacques Chirac was born in Paris on November 29, 1932, the only child of a well-to-do businessman. A lively youth, he was expelled from school for shooting paper wads at a teacher. He sold the Communist daily “L’Humanite” on the streets for a brief time.

Chirac traveled to the United States as a young man, and as president he fondly remembered hitchhiking across the country. He worked as a fork-lift operator in St. Louis and a soda jerk at a Howard Johnson’s restaurant while attending summer school at Harvard University.

Chirac served in Algeria during the independence war, which France lost, and enrolled at France’s Ecole Nationale d’Administration, the elite training ground for the French political class.

In 1956, just before heading to Algeria, Chirac married Bernadette Chodron de Courcel, the niece of a former de Gaulle aide and herself involved in local politics in the central farming region of Correze, where Chirac spent much of his youth. They had two daughters, Laurence and Claude, who became his presidential spokeswoman.

He worked his way up the political ladder and was named premier in 1974 by President Valery Giscard d’Estaing at the age of 41.

A personality clash with Giscard d’Estaing led Chirac to resign, but he quickly assumed the presidency of the conservative political party he refounded as the Rally for the Republic. He became mayor of Paris in 1977 and used the highly visible office as a power base for the next 18 years.

Chirac lost the 1981 presidential election to Socialist Francois Mitterrand, a scenario repeated in 1988. He became president at last in 1995.

Two painful setbacks in his career involved student protests: In 1986, a student was killed during protests over university reforms while Chirac was prime minister, prompting him to abandon the measure. In 2006, Chirac withdrew a measure that would have made hiring and firing young people easier after weeks of nationwide student action. He failed repeatedly in efforts to reform France’s labor rules and economy.

In recent years, Chirac was very rarely seen in public. He was visibly weak and walked with a cane at a November 2014 award ceremony of his foundation, which supports peace projects.

Chirac is survived by his wife and younger daughter, Claude. His daughter, Laurence, died in 2016 after a long illness that Chirac once said was “the drama of my life.”