The province that sits atop Portugal in the Iberian Peninsula is hardly the first region that comes to mind for Israelis when they think of destinations in Spain, although it happens to be quite popular among vacationers from that country, as well as for trekkers from the world over.

Galicia is home to the Camino de Santiago, a network of pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela that has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as well as to thermal hot springs that run underground and along rivers from central and southern Galicia to northern and central Portugal.

This abundant natural resource has led to the development of numerous spas and resorts, attracting thousands of visitors every year. The current industry is building on a tradition that is millenia in the making: baths, like bridges, were part of the infrastructure built by the Romans way back in the first century, in this far-flung outpost of its empire.

Ancient bridges and thermal fountains may still be appreciated today in the Galician city and district of Ourense, which proudly brandish the label the “thermal capital of Spain.”

One such venerable fountain, gushing water that can reach 150 degrees Fahrenheit, graces contemporary downtown Ourense, which is also where bathers may catch a convenient tourist “train” to thermal pools built along the Minho River. An inviting promotional poster shows a smiling family preparing to board the train -- dressed in their bathrobes.

Ourense has also cleverly leveraged its thermal heritage to become the global headquarters of Termatalia, a non-profit organization whose name derives from the Spanish terms Termalismo (thermalism) and Talassoterapia -- thalassotherapy, the therapeutic use of seawater. Termatalia has grown from a small regional organization in 1999 into an international organization encompassing much of Europe and Latin America.

Termatalia is also the sponsor of an annual International Exhibition of Thermal Tourism, Health and Wellness, whose venue alternates yearly between Ourense and a host city in Latin America.

The 19th Termatalia expo took place last month in Ourense, together with two other Important events for the thermal industry: the 15th International Meeting on Water and Health, and the III International Symposium on Thermalism and the Quality of Life.

Studies conducted at Galicia’s University of Vigo are validating the science behind the benefits of balneotherapy -- the therapeutic benefit from immersion in thermal waters -- for promoting wellness and treating a variety of health conditions.

Interestingly, Termatalia focuses on the culture of water as a medium of wellbeing both externally (bathing) and internally (drinking).

One of the most popular Termatalia exhibits was the water bar, where visitors could taste dozens of brands of mineral waters from all over Europe and South America.

Nearby was a towering display featuring literally hundreds of bottles of mineral water, of all colors, shapes, sizes and even unusual natural flavors, like rosemary.

On the last afternoon of the trade show, Termatalia hosted a tasting competition, with six professional water sommeliers as judges, equipped with multiple glasses, spittoons, crackers to be eaten between sips, and detailed score sheets for grading the 30 finalists.

“Water sommelier is a recognized and certified profession, like wine sommelier,” says Carmen Gonzalez, president of both the Association of Mineral Water Tasters in Andalusia and the Spanish Association of Mineral Waters. Gonzalez sat on the international panel of judges, who evaluated the mineral waters on characteristics that included aroma, taste (acid, alkaline, salty), and visual (clarity, brilliance, transparency).

In the end, prizes were awarded to winners in categories that ranged from low mineral content to high mineral content, natural carbonation to artificial carbonation, and all sorts of classifications that only a trained palate could discern.

The day after the exhibitors closed their booths, Termatalia sponsored field trips along thermal routes, another trend in the industry. Both outings involved collaborations between Spain and Portugal: the Chaves-Verin route, for example, is actually trademarked and marketed year-round as the “Euro-city of water,” with the advertising slogan “one destination, two countries.”

(Chaves, in Portugal, is also affiliated with the Roman Thermal Spas of Europe, a network of nine spas across the continent that can date their provenance to the days Roman legionnaires would rest and recuperate in their waters.)

The second thermal route is less established, as it centers around the thermal baths in the northern Portuguese city of Melgaço, which have been closed for renovations for several years; with the aid of a 7million euro grant from the European Union, the refurbished thermal center -- baths and clinic -- should re-open in the spring of 2020. Interestingly, the baths here claim a track record of ameliorating diabetes, when the waters are ingested.

The thermal waters of Melgaço also commingle, in certain sections, with the Minho River, which boasts Class I rapids; in fact, one of the tourist attractions of Melgaço is rafting, and rafters are invited to stop paddling and enjoy a dip in the occasional warm currents.

Other sightseeing attractions in Melgaço include a beautiful structure with stained glass from the early 20th century that houses one of the thermal springs; a medieval castle and tower with historical museum, surrounded by a picturesque village; a museum of cinema with rare movie posters; and a center that showcases the gastronomy of the region, especially its smoked meats and Alvarinho wine -- a highly regarded white varietal.

Once my assignment covering Termatalia was over, I wanted to take advantage of being in this seldomly visited part of Spain to explore two ancient Jewish quarters in Galicia: in the cities of Ribadavia and Monforte de Lemos.

I had discovered their existence by visiting the website of the Red de Juderias de Espana, the network of (former) Jewish quarters in Spain. It was painstaking work clicking through the 18 cities listed, since there is no link on the home page to a map pinpointing them in country.

Nor is the job made any easier by the fact that everything is only in Spanish. Most disappointingly, none of my efforts to contact the main office of the organization -- whether via the e-mail address hidden in the recesses of the website, or via Facebook -- resulted in receiving a reply.

Nor did things improve when I got to the specific Red de Juderias web pages of the two cities I had identified: neither locality responded to my inquiries. Bottom line: the Red de Juderias may do some important work in the field, but they are useless when it comes to helping tourists.

Not giving up, I was eventually able to discover there is a Galician Center for Jewish Information -- a.k.a., the Sephardic Museum of Galicia -- in Ribadavia, a pleasant little town just 20 minutes from Ourense.

It is a gem of a museum, although all exhibits are described only in Galician, a dialect of Spanish with similarities to Portuguese.

There is an English pamphlet that summarizes things, although it is hardly adequate. The good news is that there is a free audio guide that helps a little in the museum, and is at its best leading visitors around the Barrio Judio, the compact and well preserved Jewish quarter that begins right outside the museum in the city’s main square.

The highlights of the quarter are the gate in the city wall and the house of the Spanish Inquisition, complete with its coat of arms over the door (the museum also vividly documents the terrors of the Inquisition). Occasionally, as you look down along the route, you will spot the golden symbol of the Red de Juderias, the word Sefarad in Hebrew in the shape of a map of Spain.

Although there are no Jews currently living in Ribadavia -- and indeed, no practicing community in all of Galicia, from what I could glean -- some homes display exterior symbols like a mezuza or Star of David in tribute to the quarter’s history.

A tastier living tribute is a local bakery that sells an assortment of cookies that the proprietor says reflects both Sephardic and Ashkenazic culinary traditions; the decorated paper bag they come in makes a nice souvenir.

At the last possible moment of my visit to Galicia, the tourism bureau of the province’s Ribeira Sacra district came through with an invitation to visit the Juderia of Monforte de Lemos, an important hill town on a key route of the Camino de Santiago.

The knowledgeable guide they provided took me on a tour of the lanes of the city’s medieval remnants, pointing out the locked doors of an abode that was identified as the synagogue centuries ago.

Unfortunately, although the city would like to restore it, it is private property, and the current owners are not cooperating.

There is a small museum in a medieval tower that purports to have an exhibit about the Jewish quarter; unfortunately, it is closed on Mondays, the day I was there.

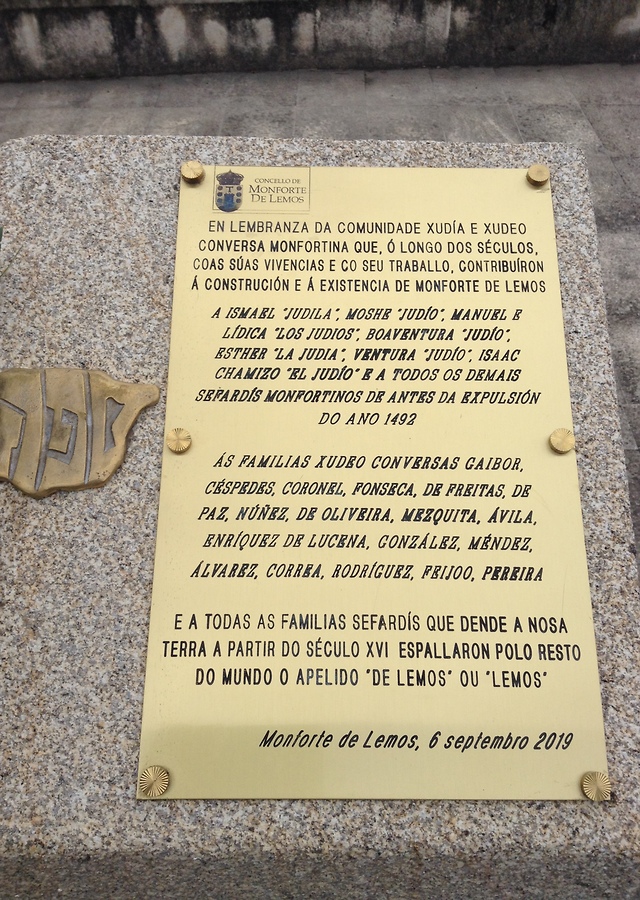

On the other hand, I did arrive just in time to see a moving plaque that had been dedicated exactly 18 days earlier to the memory of the generations of Jews that had lived in Monforte de Lemos before their exile -- specifying common first names as well as last names associated with “conversos,” and culminating in a tribute to those in the Diaspora who had subsequently incorporated Monforte or Lemo(s) in their surnames.

I flew to Spain on Air Europa, the leading low-cost airline with non-stop flights from Tel Aviv to Madrid.