Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

A new study has revealed a massive gap in digital skills between Jewish and Arab sectors in Israel, with the Arab community falling far behind. The study showed that only 13% of Israeli Arabs have moderate or high-level digital skills compared to 59% of non-Haredi Israeli Jews.

According to the study by the Interdisciplinary Center in Herzliya, a third of Israeli Arabs have no internet connection, and 87% of the community in the 25-64 age bracket lack basic abilities including emailing, online shopping, completing digital forms and using apps such as Zoom for remote learning.

5 View gallery

The Tsofen NGO teaches computer skills to members of the Arab community

(Photo: Courtesy of Tsofen)

Senior IDC researcher Dr. Marian Tehawkho, who presented the study at an annual conference earlier this week, says she was surprised by the gravity of the situation.

"The decision to conduct the study in our program, which focuses on economic policy for Israeli Arab society, was prompted by the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing social distancing that led to greater online interaction," she says.

Kehawkho says Israeli Arabs looking for study or employment opportunities have discovered they are ill equipped to deal with the new digital reality, not least of all due to a lack of necessary infrastructure in their communities including internet access.

5 View gallery

Dr. Marian Tehawkho, researcher at the IDC's Aaron Institute for Economic Policy

(Photo: Oren Shalev)

"We found many homes were there was no internet access and even where an internet connection did exist, it was often subpar and restricted proper functioning," she says.

"Even people in the academic field and senior government officials were unable to interact online due to connectivity problems. Proper internet access is a fundamental need that is no less vital than proper roads or electricity," she said.

According to Dr. Hila Axelrad, who led the study with Kehaowkho, this is not a phenomena unique to Israel.

"Minorities all over the world suffer from digital exclusion but this past year highlighted the problem," she says.

"Arabs who have digital skills are unable to work from home because of poor infrastructure. This inequity became more evident during the pandemic and will only grow with more digital tools becoming available."

The study compared the situation in the Arab community to the non-Haredi Jewish sector, looking at computer literacy and infrastructure. It also compared Israel to other countries around the world.

"The decision to exclude the Haredi sector from the comparison was made because in the ultra-Orthodox sector, which suffers from a poor socioeconomic status, digital ineptitude is self-imposed and the result of cultural resistance, whereas the members of the Arab sector wanted to join the digital world," Axelrad says.

"There is no religious impediment to using digital tools in Arab society," Kehawkho says. "There is only resistance to certain websites."

The study found that the Israeli Arab sector rated badly in testing based on the OECD Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, with even poorer results that in Turkey, which scored lowest overall among OECD nations.

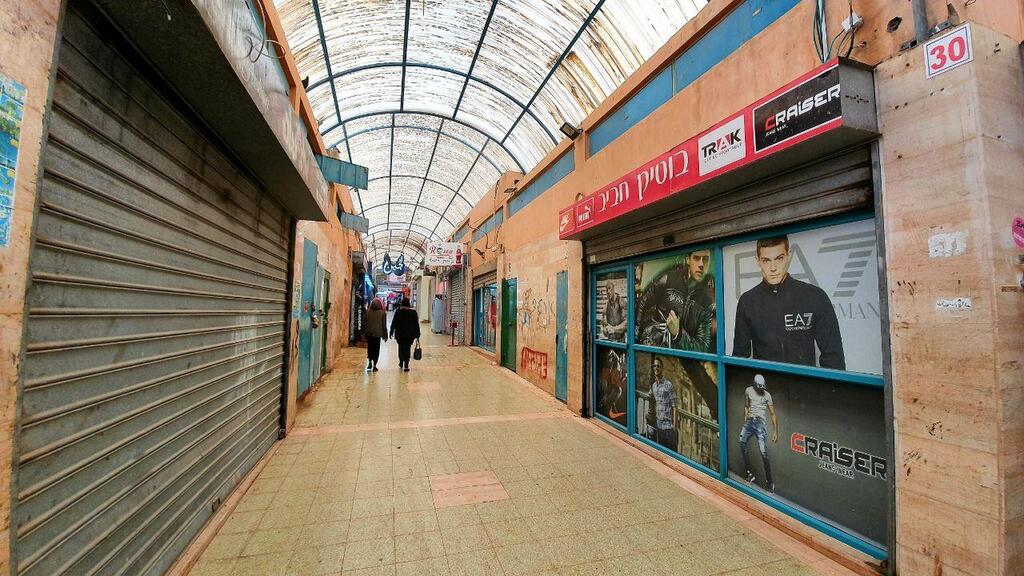

5 View gallery

Businesses shut down in the Bedouin city of Rahat during the coronavirus pandemic

(Photo: Roee Idan)

In both non-Haredi Jews and Arabs, ability levels increase among the younger population but the gap remains consistent.

For example, among the 25-44 age group, 73% of non-Haredi Jews rated high compared to just 17% the Arab sector. And in the over-65 bracket, 23% of non-Haredi Jews showed some digital aptitude compared to 0% among Israeli Arabs.

The researchers presented a number of recommendations to rectify the situation:

- The state establishment of digital centers in the Arab sector to provide short-term solutions for employment and educational needs

- Investment in infrastructure for a long-term response to the shortfall, including financial incentives for internet service providers to operate in areas that do not yield immediate profits

- The provision of courses for unemployed Arab citizens, to educate them in the use of digital tools and specific programs directed at small businesses

- Educational programs in schools for students and faculty as well as digital training for municipal workers in the sector in order to improve online services

"The first push is needed and schools and universities can easily provide it. The pandemic saw advances that otherwise would have taken 10 years, allowing Arabs the time to catch up with otsectors of the population, but now they are falling far behind and are being kept out of jobs and academic opportunities. This must be dealt with in order to allow Arabs equal opportunities for success," she says.

"This is not beyond our reach," Kehawkho says. "I don't mean every Arab citizen should become a computer engineer in the high-tech industry. I'm just suggesting that the minimal tools to navigate the modern world must be available to all."

The Tsofen NGO, for example, is an organization based in Nazareth and Kafr Qasim that seeks to expand Arab participation in Israel's renowned high-tech industry "as an economic lever and catalyst for shared society."

Axelrad adds that with a new government announcing financial investment in digital infrastructure and advances in online government services, it must understand that there are sectors of the population who will not have access to them.

"The government must take into consideration the members of the population who do not have access to the internet and work on rectifying the problem before the gap between the Israel's Arab community and non-Haredi Jews widens further," she says.