Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Steve Jobs had a disdain for the Apple Newton. One of his initial moves after returning to the company he co-founded in 1997 was to ax it – a groundbreaking product designed to salvage Apple's finances. Nevertheless, without the Newton, we likely wouldn't have known the iPhone or the iPad.

Read more:

The Newton was launched in August 1993, exactly 30 years ago. This era marked the dawn of the internet, with the masses not yet connected, and the most popular computer was the PC with Windows 3.11. Few computers utilized a mouse, like the Atari ST or the Commodore Amiga, and touch recognition on black-and-white LCD screens was limited to very few products, like the British Psion. Handwriting recognition hardly even existed.

Interestingly, during that time, John Sculley, Apple's CEO and the man Jobs referred to as a "sugar-water salesman," decided to embark on a project that felt like something out of science fiction. The idea was simple: create a Personal Digital Assistant(PDA). Not many know this, but the term "PDA" was actually coined by Sculley. It was a testament to the fact that even he had his moments of brilliance. He introduced the term when unveiling the Newton in 1992, a year before its launch. The term was so catchy that it continued to be used to describe a whole realm of similar products: from the legendary Palm Pilot, Windows CE-based handheld computers, all the way to the first BlackBerry smartphones, dubbed "smartphones with integrated PDAs."

However, to be truthful, Sculley wasn't the first to conceive of the Newton. It was actually an initiative by Apple's Vice President of Research and Development at the time, Frenchman Jean-Louis Gassée. He began working on the concept in the late 1980s and presented the project to Apple's board in late 1990. However, Gassée clashed with senior management and left the company that same year. The project was saved by Bill Atkinson, one of the veteran engineers and the mind behind the graphic interface development for the Apple Lisa, the computer preceding the Macintosh. Atkinson asked Sculley and other senior figures for ideas on how to advance the new product. Sculley was the driving force in the team and contributed ideas that today seem trivial to us, like connecting to databases, galleries, and using windows to switch between applications.

As a PDA, the Newton was remarkably advanced for its time. It allowed you to jot down notes or memos, had a calendar, a contacts application, a calculator, and of course, you could send faxes. Oh, and of course, you could send and receive emails. Not that many knew what email was in 1993. Newton did all of this in a format that could fit in your pocket—maybe not your jeans, but definitely your coat, provided it was deep enough. But that was Sculley's demand—an all-in-one pocket computer.

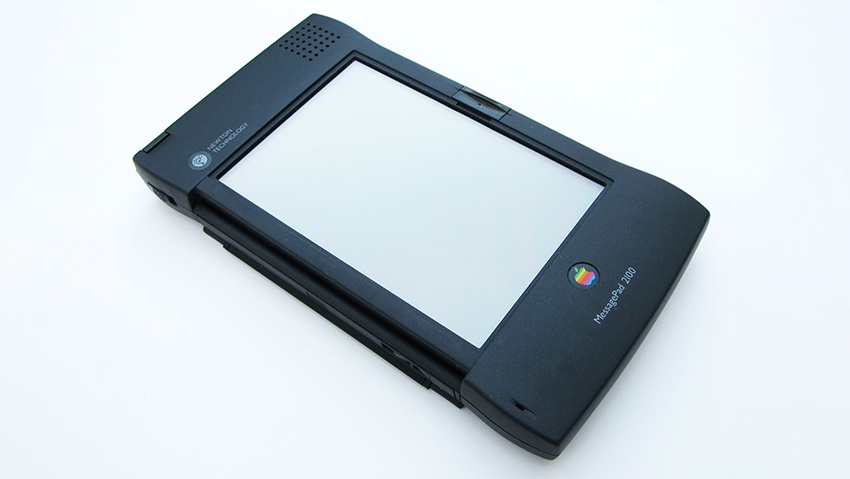

Despite us knowing the Newton mainly as an electronic organizer, in reality, it was a series of products that included a type of portable computer intended for the education market—a kind of precursor to Google's Chromebooks today. As mentioned, Apple introduced the first product in 1992 at that year's CES exhibition. The product immediately captured the imagination of devoted Apple enthusiasts. However, when it was launched over a year later in the summer of '93 at a price of around $900 back then—equivalent to roughly $1,500 in 2023—only 50,000 people ordered it. Shortly afterward, the company introduced the MessagePad 120, an improved version with a detachable keyboard that could be connected via a cable. Apple later introduced an enhanced version of the operating system. Its advantage was the ability to switch between portrait and landscape modes, although this required recalibration each time.

However, the handwriting recognition engine of the Newton had a lackluster performance, to say the least. Writing a short message could take much more time compared to typing on a keyboard. While Apple did manage to improve the capabilities over the years to a level that even impressed users long after, it was too little too late to salvage the concept. When Jobs returned to the company, he didn't see Newton as a viable foundation for his mobile vision, which began in 2001 with the iPod and continued with the iPhone and iPad. Jobs had a strong disdain for styluses and believed that touchscreens should be controlled by fingers. This, combined with the remarkable success of the Palm Pilot, which despite its technological limitations was much cheaper and user-friendly, led to the demise of the Newton product line.

Nonetheless, many of the development team members from the Newton continued to serve in the development teams for the iPhone and iPad, showcasing a direct connection between the various products. And since then, even the concept of styluses has returned to Apple through the Apple Pencil, designed for use with the iPad.

The Newton wasn't just a technological milestone for Apple; it inspired the entire landscape of mobile devices. Its processor architecture, developed by the British company ARM, has been a foundational element for smartphones, tablets, and even certain types of Windows PCs, as well as current Mac computers (M1 processors). The connection between Apple and ARM began with the Newton, leading to developments that eventually influenced the iPhone's creation. It's highly conceivable that without the Newton, we might have been carrying smartphones with Intel-based chips today.

The universal search function also made its debut on the Newton, and now we see it in the Mac as Spotlight search, as well as in Android smartphones and even Windows systems. There aren't many products that failed so significantly yet managed to spawn so much technology and innovation over the following 30 years. The Newton is one such case. Without its failure and the resonating lessons it provided, the smartphones we use today might have looked vastly different.