Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Ariel Tiger is no longer surprised by online human trafficking, organ trading, counterfeit goods and arms dealing. After all, this is his reality on a daily basis at work.

ISRAELI RESEARCH TEAM REVEALS MINIATURE HUMAN HEART

Read more:

Tiger is CEO of EverC, an Israeli startup specializing in risk management and AI-driven insights for e-commerce and online payment providers. From his vantage point, Tiger attempts to explain these phenomena and also offers solutions for combatting them.

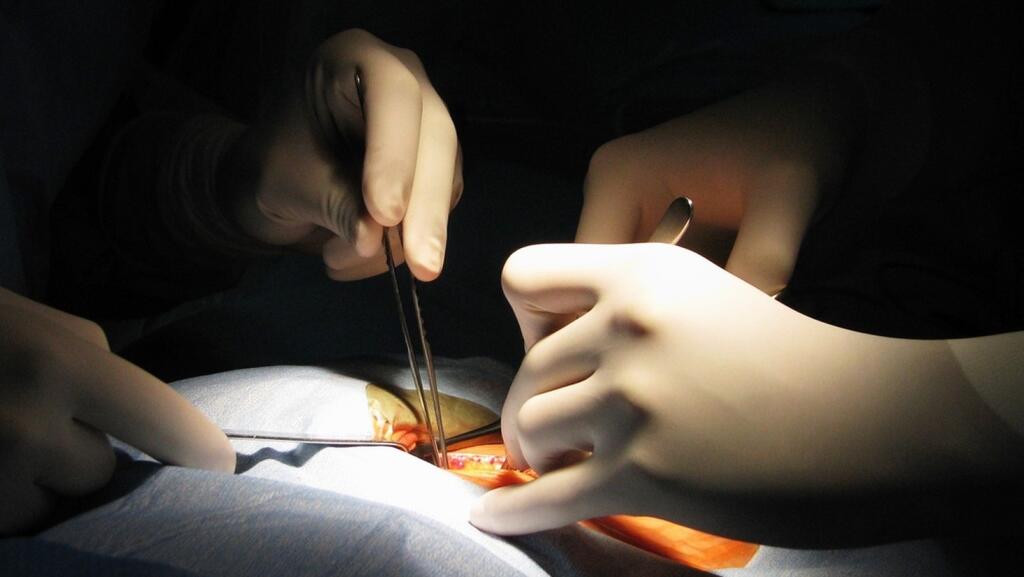

"Organs make their way into the market for various reasons. Sometimes it's an individual who got involved with the mob or the black market, and a criminal organization offers them the option to pay off their debt in exchange for an organ. At times, organ trafficking occurs during trips, where locals in different countries provide assistance to individuals in dire situations, offering them medical care when urgent surgery is needed to save their lives," he explains.

"However, this is only a cover story, and the victim awakens after surgery without a specific organ. Organs obtained through such means are sold for exorbitant sums in anonymous locations like the dark web. There are thousands of private networks that allow people to communicate under anonymity, engaging in illegal activities," Tiger says.

Tiger explains how his company attempts to address these issues.

"Just last May, one of our analysts updated us about a suspicion that organ trafficking was occurring on a website under the cover of a different narrative. She identified the pattern, which involved accessing a specific site on the Deep Web (a part of the internet not indexed by search engines), and from there establishing a connection to an internet site where legitimate payments could be made. Although they were requesting payment for legal goods, it was evident to her that organs were being exchanged for transplantation. She persisted, began corresponding with those traders, and obtained prices. For instance, the price for a heart stood at $1 million, while a kidney was sold for $200,000, and the traders provided 'catalogue' images for each."

"Subsequently, they sent her several bank account numbers for transferring the amount, or specific account numbers on certain platforms through which the payment could be made, and that's exactly what she awaited," Tiger says. "Our investigation focused on understanding how the sellers receive the money when the intention is not for cryptocurrencies, but for the moment when a legitimate payment medium becomes involved, like transferring payments through trade platforms of consumer products, where many of us have accounts. Since significant amounts cannot be transferred through such accounts at once, the sellers requested that the sum be divided into smaller amounts, which would be transferred through different payment channels."

"When we were certain, we approached our clients, some of whom are among the largest banks in the world, and credit companies, obligated by law to report to authorities when they receive information indicating a crime. Several weeks later, the company received a phone call from one of the major banks where they understood that this trafficking was affecting them. They thanked us and passed this information to law enforcement authorities," he says.

"We're aware that about 16% of the websites claim to sell one thing but actually sell something completely different. Since the transactions go through banks and credit card companies, as well as major financial institutions online, they, along with significant commerce entities, need to know what's occurring on these sites – and they are our clients. That's why they also invest substantial sums, in the millions of dollars, in us."