The first time I drove on a German autobahn was actually in Austria. I had rented a Mercedes with Hans, a fellow journalist, and we set off from Vienna toward the German border.

"I’m tired, you take the wheel, and we’ll switch later," Hans said as the Austrian autobahn opened up before us: four wide lanes, trucks to the right, impressive tunnels. Yet, despite the perfect conditions, we couldn’t really speed up.

Every few kilometers there was a toll barrier, and even without them, the speed was capped at 130 km/h. It felt like owning the latest smartphone but only using it for calls. Hans reclined his seat and promptly fell asleep.

Just before we crossed into southeastern Germany, he woke up and asked me to pull into the nearest service station for a restroom break, coffee and a cigarette. When we were done, he asked for the keys. On the German autobahn, there are no toll barriers. For the first part of the road, the speed limit remained 130 km/h, so I reclined my seat and planned to relax. A sign appeared, warning of wet road conditions and temporarily reducing the speed to 80 km/h, and Hans followed it dutifully.

Then, a few kilometers later, I saw a road sign I’d never encountered before: a white circle with five black diagonal slashes across it, meaning no speed limit from this point until further notice.

"Yes!" Hans cheered, clenching his fists in excitement. He floored the pedal, and the needle jumped to 200 km/h. Mathematically, that’s a landscape disappearing at 55 meters every second. In practice, it feels like watching your life flash by in a blur.

I remember two things from that drive: the intense concentration, the rush of adrenaline even though I wasn’t the one driving, and especially the fact that for a significant part of the ride, even as we neared 200 km/h, we had to move aside in the left lane for cars that were going even faster.

No country is as obsessed with driving as Germany, nor does any other country allow speeds of up to 400 km/h—or even higher—on public roads. In fact, there isn’t a single racetrack worldwide that permits standard production cars, as opposed to race-designed vehicles, to reach such speeds.

Back to the Third Reich

It’s a delicate subject, but some Germans will admit that the man regarded as pure evil, Adolf Hitler, did a few things that benefited Germany, such as drastically reducing unemployment, which had fueled his rise to power. One of the main projects that increased the workforce almost immediately after the Nazis took power was a law passed in June 1933 to build the Third Reich’s network of highways—the autobahn.

The Nazi party allocated generous funding to the project, appointed Fritz Todt as its general supervisor, and launched the construction of the first autobahn between Frankfurt and Darmstadt in August 1933, which culminated in a grand opening ceremony on May 19, 1935. The plans, however, were not Hitler’s own; they had been meticulously drawn up by engineers over nearly seven years during the Weimar Republic but had lain unused due to lack of funds and political interest.

Initially opposed to building autobahns, Hitler soon made them his personal project upon taking office. Yet, within a few years, Germans discovered he had little interest in the comfort of their travel, in the number of lanes or rest stops, or in their eagerness to drive at high speeds. Hitler viewed the autobahn as critical for one purpose only: Germany’s territorial expansion. Fast-tracking autobahn construction was his way of building the logistical network to quickly move troops into neighboring countries.

Even under the Weimar Republic, Germany had already begun to embrace a love of automobiles: between 1924 and 1932, the number of vehicles in Germany increased from about 125,000 to nearly half a million, which drove demand for roads. The result was twofold: as highways were developed as architectural monuments for leisure drives spanning hundreds of kilometers, the demand for cars grew, making Germany’s automotive industry the giant it is today.

More and more autobahns were constructed. They were numbered, each designated with an “A” followed by digits: one-digit numbers were assigned to autobahns that crossed Germany, and two digits to those connecting cities or regions. East-west routes were given even numbers, north-south odd ones, and each region received a block of numbers.

Branded “The Roads of Adolf Hitler,” the autobahn project served both military purposes and modernization of transportation, while providing tens of thousands of jobs and symbolizing the strength of the Nazi party. By the time projects were frozen in 1941 due to the war, 3,820 kilometers of autobahns had been built.

Toll-free vision

By 1943, Germany’s new autobahns were being used by the military, and at times served as runways for fighter planes. With traffic sparse, even cyclists were allowed to use the broad lanes. Most roads were built from concrete, with the remainder paved with asphalt, and each direction featured 24-meter-wide lanes without shoulders or interchanges. Engineers were directed to maintain even elevations and limit curves as much as possible. The budget for this monumental project was set at 6.5 billion Reichsmarks (equivalent to €26 billion today), intended to be financed through bank loans, grants from the Reich’s autobahn office, and a proposed road toll—though that idea was quickly dismissed. Instead, a tax on car owners and fuel prices was imposed.

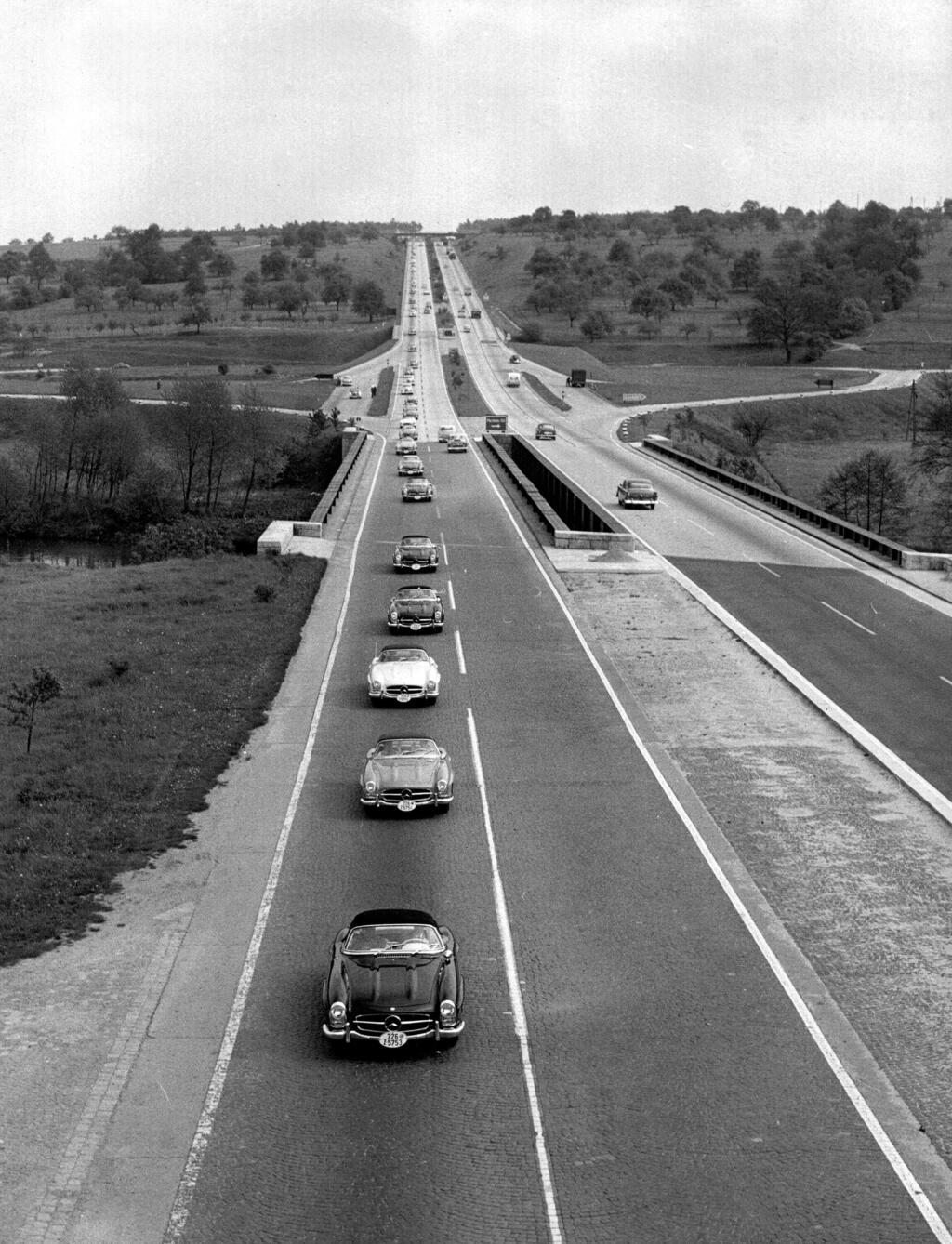

Beyond boosting employment and providing strategic military infrastructure, the autobahns were meant to project aesthetic grandeur and patriotic pride. Anyone who traveled on these roads would notice a striking uniformity—once you’d seen one, you’d seen them all. Built to convey unity and nationalism, they showcased Germany’s scenic beauty and fostered loyalty. Photos of the autobahn stretching from Munich to the Austrian border, with breathtaking views of the Alps, won international acclaim. The autobahns were designed to glorify the Nazi regime, both domestically and in the eyes of the world, often compared to historical monuments like the Egyptian pyramids, the Acropolis in Greece, or the Great Wall of China.

The project spurred an industry around it, producing games, postcards, stamps, exhibitions, and annual calendars. Since the new highways avoided intersections, Nazis constructed bridges over valleys and rivers, transforming these structures into architectural showcases, comparable in scale and ambition to the cathedrals of old.

Inspiration for America

Visitors to Germany, especially during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, saw the autobahn construction as a symbol of German progress. That year, with the world still reeling from the Great Depression, Germany created 400,000 jobs in autobahn construction and its associated supply and logistics. Dwight Eisenhower, who as an officer witnessed the autobahn’s civilian and military utility, used it as a model for America’s interstate highway system in the late 1950s. He would not be the last to take inspiration from the German autobahn project.

4,000 bridges in need of repair

After WWII, West Germany embarked on extensive efforts to repair and complete the autobahn system, which played a crucial role in Germany’s post-war economic boom. Yet, many plans had to be adjusted due to shifting borders and Germany’s division. While much of the construction continued into the 1980s, certain sections were only completed following reunification. Meanwhile, East Germany’s autobahns fell into disrepair, primarily serving military and agricultural vehicles. In the West, drivers could reach speeds up to 432 km/h, while in the East, speeds were capped at 100 km/h.

Following reunification, Germany’s federal government invested heavily in restoring the autobahns in the former East (much like the investments made in eastern cities). However, Germany’s autobahn network—totaling 13,192 kilometers—now suffers from significant maintenance needs. Some 4,000 of the country’s 28,000 bridges require immediate repairs. Germany’s Ministry of Transportation announced that 5.5 billion euros are needed for modernization, but due to economic pressures from the war in Ukraine, the 2025 budget has been slashed from 6.29 billion euros to 4.99 billion euros. With these budget constraints, discussions of road and bridge closures due to safety compliance issues are now becoming a reality.

Many roads in former Nazi-occupied and annexed territories remain intact; others have been restored and replicated, with speed limits and tolls added. Today, Germany’s autobahn network looks quite different from the original layout, with more interchanges, wider shoulders, additional lanes, billboards, and emergency call boxes. Currently, there are about 150 call boxes—down from 17,000 in the pre-mobile era, which averages four calls per kilometer. Every 50 kilometers, rest areas offer fuel, food, drinks, and even accommodations, with a dedicated police division overseeing the autobahn system.

One unique feature persists: travel on Germany’s autobahns remains toll-free for all vehicles. This irks many German drivers, who must pay tolls in neighboring countries where speed limits are stricter, typically capped at 130 km/h.

Is speed a danger?

Car organizations in Germany argue that the country, now distanced from its Nazi past, should promote personal freedoms, including drivers’ choice of speed. In contrast, environmental and safety advocates liken the unlimited speed rule to outdated policies, such as public smoking allowances.

Despite the average autobahn speed hovering around 125 km/h, with 35% of vehicles exceeding 130 km/h, accident rates are comparable to the autobahn’s usage, if not lower. This statistic accounts for factors like the absence of pedestrians and cyclists. Germany’s fatal accident rate per vehicle kilometer remains one of the lowest in the West.

From a practical infrastructure with a dark history, the autobahn has transformed into an iconic global symbol of Germany. The electronic band Kraftwerk even released a single and album titled "Autobahn" in 1974. As environmental concerns grow, there are increasing calls to halt new autobahn projects in favor of public transportation alternatives. It’s possible that the autobahn may eventually become a monument to a past Germany might prefer to forget.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: