Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Few of those working at Israeli hi-tech’s great hope, Yokneam-based computer giant Mellanox, would admit it, but they were shifting uneasily in their seats four years ago as they learned the 20-year-old company was being sold to chip giant Nvidia.

The American mega-company has made a name for itself in gaming and high-quality graphics cards for PCs and is famous for its colorful CEO, Jensen Huang, rarely seen without his trademark black leather jacket.

They’ve since changed their minds. The AI era has turned the company into the hottest thing in the global tech market. With unprecedented speed, Nvidia became the world’s third-largest company – overtaking Amazon and Google with a market surpassing $2 trillion, annual revenues of $61 billion, net profits close to $13 billion, and a company stock price increase of 2000% in just five years.

It’s simple: Nvidia has supplied the whole world with computing capabilities that have enabled a relatively easy transition to AI, such as training and running large language models such as ChatGPT.

The supporting technology helping Nvidia achieve this comes from its branch in Israel – formerly Mellanox. You’ll soon understand how.

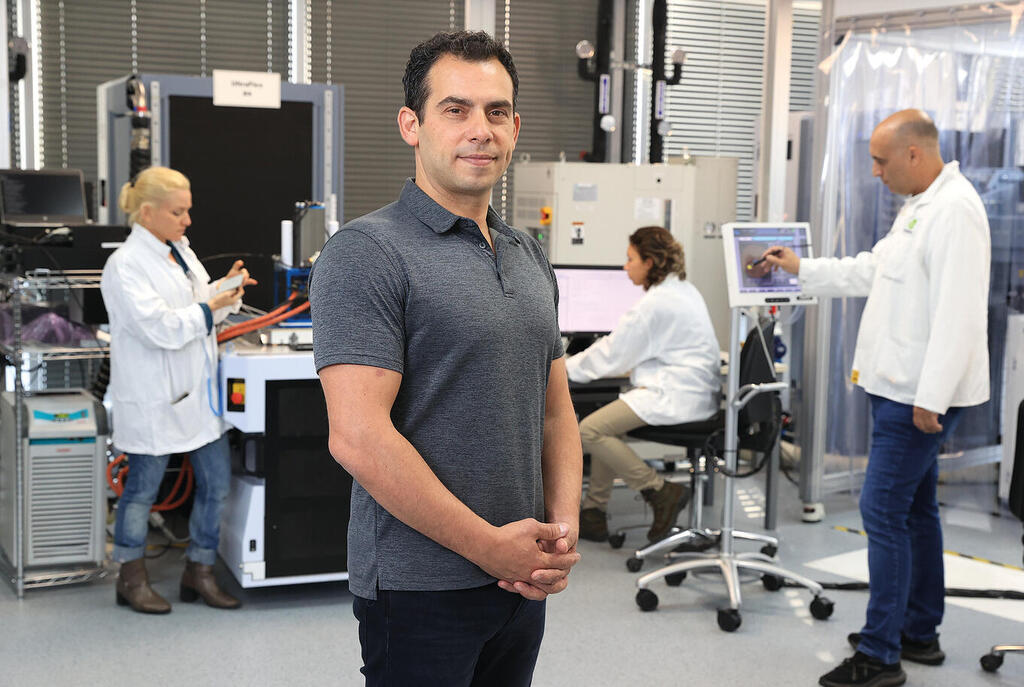

“At Mellanox, we were very familiar with Nvidia. It was a client of ours,” 50-year-old Amit Krig, senior vice president of software R&D at Nvidia and head of the company’s Israel development center, says during our visit to the company’s offices in Yokneam.

“We knew Nvidia was much more than a gaming company. We were familiar with its high-performing computing (HPC) and parallel computing technology. Not that I have a problem with gaming. For years, my kids at home had no clue what I do at Mellanox. When we became Nvidia, it was all about respect that Dad works there.”

Mellanox founder and fresh Israel Prize recipient Eyal Waldman, who served as chairman and company CEO, was actually against the deal at first – and not because of its image. He was sure, and in retrospect was right, that the company was worth even more than the vast sum of $6.9 billion for which the company was ultimately sold. Waldman fought and argued, but eventually agreed with the board’s decision to approve the deal.

Waldman owned 3.61% of the company and is believed to have made $245 million on the deal. Making $393 million, US investment fund Starboard which owned 5.8% of the company raked in the most. Four years on, Bipetal conservatively estimated last March that shares and options of the 1,500 – 2,000 Nvidia employees in Israel have reached an average of $400 – $500 thousand each (totaling 1.5- 1.7 million shekels). This is just the average. Many have made over $1 million.

“Like in a relationship, we had our doubts at first,” says Krig. “Integrating the company claimed an emotional toll. Especially when it’s selling a very Israeli company to an American company with its own structured methodology, rules and ways of doing things.

“I’ll admit that at the beginning, I told myself it wouldn’t be the same anymore. But almost all the company’s senior executives have remained in their positions. Our employee loyalty ranks among the highest in the industry, and within the company, our product contributes to our success significantly. I’m sure that one plus one has given us more than three,” he says.

“An emotional bond between people from different countries working together has also been formed. And that’s before talking about the extraordinary personal relationships our directors have with the CEO, Jensen Huang. I can say that the company has become a home again. I now even feel at home walking around [Nvidia headquarters] in Santa Clara.”

Unlike international behemoths like Apple and Microsoft, Nvidia doesn’t shy away from giving full and open credit to its Israel branch.

With four sub-branches in Tel Aviv, Raanana, Be’er Sheva and Tel Hai, with 4,000 employees (double the number at the time of acquisition) dealing with all the global company’s products, the Israeli branch is the company’s second-largest after the US.

The company also announced this week that a further 100 employees will be joining its ranks, following its purchase of Israeli AI network management startup Run: Ai, a deal estimated to be worth some $700 million.

It was also revealed this week that Nvidia is in advanced negotiations to purchase Deci, another Israeli AI startup.

Huang, who emigrated to the United States from his native Taiwan at the age of nine, ranks among global hi-tech’s greatest fans and misses no opportunity to shower praise on his Israel branch. In the stormy early days of Israel’s war with Hamas in Gaza, his videos and e-mail are among the industry’s most moving:

“The world follows the news out of Israel with horror. The scale and brutality of the attacks and the suffering they inflect are difficult to fathom. For our families in Israel, the news is a living nightmare,” he reportedly wrote in a missive to the company’s staff.

“We have 3,300 Nvidia families and many friends in Israel. Nearly 400 of our employees have returned to military duty. Our thoughts are constantly with you, and we hope for your safe return,” he said.

“Many families must evacuate their homes. With incredible acts of kindness, hundreds of Nvidians are volunteering their support and making room in their homes for Nvidia families who have left their neighborhoods for safety. We will provide those families with whatever help they need.”

The company supported in its own way, paying out $10,000 grants to each Israeli employee.

Huang also shared a eulogy for Danielle, the daughter of his good friend Eyal Waldman, who was murdered along with her boyfriend Noam Shai in the slaughter at the Nova music festival on October 7.

The company is also keeping close contact with the family of computer engineer Avinatan Or, a company employee kidnapped to Gaza on October 7 along with his girlfriend Noa Argamani. At the end of last year, Nvidia announced a $15 million donation, the company’s largest ever, to organizations supporting victims of the war.

The Magic of Mellanox

The main “engine” of every computer on Earth is a central processing unit (CPU) produced by companies such as Intel, AMD and Apple. For years, Nvidia has focused its efforts on developing and producing graphic accelerators. Over the years these chips, known as GPUs, were designed for gamers, designers and programmers requiring advanced graphic performance.

When the AI buzz kicked off, Nvidia won the lottery. In 2012, almost by chance, a group of Toronto University researchers discovered that its advanced graphic processors are more suitable than “regular” GPU processors for training and running AI models. Overnight, GPU became the technological basis for many advanced AI projects.

Jensen and his colleagues immediately realized they had been touched by the hand of God and were quick to respond. They knew about the AI boom beginning in startups and academia even before the big companies did and wisely developed tools to train and run AI models on computer systems with GPU chips that quickly became the firm favorite for researchers and programmers alike.

In 2016, Nvidia Israel’s senior company director, Nati Amsterdam, joined what was a small Nvidia branch - an R&D center that included a sales group.

“We went to research departments at universities,” says Amsterdam. “We met startup companies. We went from one industry to the next, mapping each of their needs separately. At the American headquarters, we built program platforms for each field,” he says.

“And in the early meetings, we realized that both top researchers and CEOs in the field were gamers. They all knew about Nvidia from their childhood PCs, or they’d bought their children such [graphic] cards. We offered them acceleration in training models – imperative for the AI process – as well as creating new capabilities from the information they already had, and insights and recommendations on what it can mean, far beyond routine analysis.

Meanwhile, in Silicon Valley, Nvidia conducted an aggressive acquisition campaign of companies in complementary fields that would enable it to offer the new industry, including its major players, a strong and complete product.

Israel’s Mellanox was perhaps the most important of these companies, as it had solved a problem that Nvidia had barely addressed.

GPU chips perform decently enough, but for vast AI tasks, you need to have lots of them operating together so they can work on huge networks as well as PCs.

“When you accelerate an image recognition algorithm,” Krig explains, “you can accelerate it on a single GPU chip. But when you want to accelerate something more challenging on an infinite database, this chip needs its friends. And for it to work faster and more efficiently, you need us.

“Until Mellanox came along, connecting computers was so inefficient that efficiency would actually decrease the more computers you connected. At Mellanox, in around 2004, we created a cluster of 1,000 Apple chips that with our technology instantly became the world’s third most powerful computer – and for a cost of just $5 million,” he says.

“You must understand, the world’s #1 computer was three times more powerful, but at $500 million, cost a hundred times as much.”

This was precisely Mellanox’s magic: creating super-fast connectivity between processors. Mellanox could not only prevent decreased network performance but also increase its reliability.

And Mellanox brought to the world the DPU, a special processor that works as data is being transferred online and further optimizes the work of many more processors at the same time - and does so at record speed.

Eighty percent of the network hardware in data farms across the globe is made by Mellanox. In short, Mellanox was a golden egg.

On an unrelated matter, but at the same time, Nvidia expanded its R&D centers in Israel with a group developing AI, and future processor systems for robotics and vehicles. The company also owns an R&D center in the new city of Rawabi in the Palestinian Authority-controlled West Bank. The center was founded back in 2010 by Mellanox and employs 100 engineers. Through contractors, a small team was employed in Gaza from 2016.

“At this stage,” says Krig, “due to the war and the client’s request, this [Gaza] collaboration has been stopped.”

Growing up with Polish and Yiddish

Krig was among Mellanox’s first employees, joining a year after the company was founded. He lives in Tivon with his wife Adi, a children’s yoga instructor, and his three children – daughters Yael,17, and Maya, 14, and 12-year-old son Nadav.

His personal story is far from the stereotypical image of a start-up dude and successful Tel-Avivian hi-techie. He was born in Haifa to parents who divorced when he was three. After his father left Israel, he, his mother and two sisters drifted between apartments in the Haifa area, and the mixed, troubled Halisa neighborhood in the northern city itself.

His mother and younger sister emigrated to the United States when he was eight, and Amit and his older sister moved in with his Holocaust-survivor grandparents from Poland, who effectively raised them from that point. Thanks to his elderly caretakers, Krig speaks fluent Yiddish and Polish.

Despite this family instability, with Amit constantly transferring schools, he always excelled at physics and mathematics. After his IDF service as an investigator in the Military Police Criminal Investigation Division, he studied computer engineering at the prestigious Technion – Israel Institute of Technology. By the end of his first year of studies, he started working at Intel, and moved to Mellanox in his fourth year.

You moved from a big company like Intel with all its great conditions to a brand-new startup?

“Yes. There was something electrifying in the air there. There was a young spirit, a feeling of change. There is also something else important. We knew that Intel’s main architect, Michael Kagan, who was extremely respected in the company, had left Intel for Mellanox. He’s now Nvidia’s CTO. When I told my manager at Intel that I was moving to Mellanox, she said that if Michael Kagan’s there, it must be an excellent startup.

“The move wasn’t easy. I moved from an environment that was financially rewarding, orderly, systematic, clear and organized - to a chaotic place. Mellanox at the time was working out of home goods producer Soltam’s old building in Yokneam. In the early years, we’d work through to two or three o’clock every morning.

What was so attractive for you guys?

“The originality, the feeling we were going to do something no one had ever done before and that you’re playing an important part in it.”

What was so revolutionary about Mellanox’s idea?

“Think of the road network we all know. It’s made up of main roads, sideroads and traffic lights. When you get to an intersection, you’re stuck in a traffic jam.

“Imagine if you could, in one go, increase the road width tenfold, or like with Waze, receive recommendations and wait five minutes for the light to change before leaving the house. If they were all coordinated, we’d all be driving around with no traffic jams. Convert that to a computer network and you’ll get the idea. “

So, the world needs this solution. But not everyone has adopted your products.

“We were offering much better products than those that existed, but we didn’t have access tools for the old classic network protocol that Ethernet was providing at the time. We didn’t even have tools to monitor performance.

“Imagine me now inventing a connection that’s more efficient than the USB phone and computer plug. The cables you have at home would not be suitable for it. The same goes for all the companies’ connections on the market.

“It takes a long time for an innovation to integrate into the market and for the computing industry to start investing in adapting to it. The added value that my invention brings to the table has to be extremely high when compared to what we have now.

“In 2005, the first computer cluster we launched was just this. It was a knockout. The classic Ethernet is still suitable for lots of basic networks, but out unique technology named Infoganda flourishes primarily in places requiring very aggressive research and calculations, such as doing accurate weather simulations or running a chat service like ChatGPT that serves billions.

"These days, you and I need a supercomputer almost every day. When you want ChatGPT to rewrite an e-mail for you or summarize the text, you wouldn’t know that there’s actually a supercomputer working away in the background, activating dozens of GPU processors.

“And this need is growing exponentially. Training AI models to create images, movies and cars requires enormous processing power. We’ve reached the point where AI engineers use AI models to create AI. Development times are constantly being reduced as everything is being built on whatever preceded it.

Super Yokneam

“The euphoria is exaggerated and will pass. Nvidia enjoyed almost complete monopoly in the field at the end of 2023, and almost every company wanting to train AI models needed to buy a GPU processor from Nvidia. By mid-2024, there’s a list of mega-companies such as Intel, AMD, Qualcomm, Microsoft, Google and Amazon, alongside dozens of startup companies in Israel and overseas, investing efforts in developing competing processors.

“Some aren’t focusing on AI training and learning processes, but rather the “inference” process – the learning application stage that follows. Two weeks ago, Intel announced its new AI accelerator and a system that simulated brain nerve cells to perform AI tasks.

“There’s competition. There always was, there always will be. There are always alternatives. It just pushes us to be the best all the time; it’s very healthy. Every morning, I’m afraid someone will overtake me and I’m always thinking about what to do to stay in the lead. Nvidia still has the advantage of offering a complete solution including not just the chips, but also the graphics cards and the program. I have enormous respect for Intel and other companies, but when I look at the complete solution, I think we’re at least a generation or two ahead of everyone else.”

Last May, Nvidia unexpectedly announced it was building headquarters for the Israel-1 supercomputer, one of the most powerful computers in the world, in Yokneam. The computer is already running and is based on communication technology that was developed in Israel and should speed up cloud performance for AI calculations.

In the first phase, it’s being used for research and the internal development of the company and its partners. It will later be integrated as part of the AI service in the cloud that the company provides to the industry in Israel.

Why do we need an Israeli supercomputer?

Krig: “The Israel-1 has two goals. Firstly, to develop a technology called Spectrum X, which is an accelerated Ethernet communication network that improves efficiency and performance via the cloud. If lots of users run on it at the same time, they each get maximum performance without interruptions. It’s 30-40% more efficient than the regular Ethernet network.

“Israel-1’s second goal is making immense computer power accessible for AI training for startup companies, partners and researchers in Israel. We’ll have remote access to it by the end of the year.”

Do you agree with the criticism that the Israeli government hasn’t invested enough in AI and that’s why Israel isn’t leading in the field? That more could have been done?

“Yes. There aren’t enough companies in Israel dealing with the field. It’s also reflected in the infrastructure. Let’s say there’s a company in Israel developing a new AI model demanding infinite calculation power. The company won’t find such calculation power in Israel. It requires electricity, location and massive purchase of costly processors.

“This is one reason why we decided to build the Israel-1 here, and to make such capabilities accessible to startups – to influence the Israeli [hi-tech] industry. We’re already in contact with around 1,000 startups aiming to accelerate their growth. AI can’t develop in Israel without it.”

What does Nvidia have to gain by investing in startups?

Nati Amsterdam: “Jensen Huang always says ‘It’s important for the process, not necessarily the result. The result will come along later.’ Although startups don’t buy our products in large volumes as the big companies do, the global implications of working with them are enormous. If we support startups that have the potential to solve complex problems, it’ll save a great deal of money in the competitive world.

“And when the time comes, and it’s running with our help in the banks in Europe and North America or the industry, Nvidia will be able to make billions out of it. For Nvidia, it’s clear that what’s being done here in Israel will affect multitudes across the globe. It’s win-win.”