Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

In an effort to maintain the appearance of normalcy, Iranian oil minister Mohsen Paknejad made visits to the country's major oil and gas facilities on Saturday. His itinerary included the coastal city of Asaluyeh, a critical hub for Iran's energy sector, and Kharg Island in the Persian Gulf, which serves as the main oil export terminal, responsible for 90% of Iran's oil exports. The timing of these visits is noteworthy, especially as global media outlets are abuzz with discussions about the potential energy market impacts if Israel were to strike Iran’s facilities following last week's missile attack on Israel.

The world's concern is less about Iran's oil sector itself and more about how Iran might respond to an Israeli attack. While Iran's oil production is on the rebound, currently estimated at around 3.5 million barrels per day (about 4% of global demand), half of this is exported. Iran claims its oil export revenues last year were approximately $35 billion, crucial for sustaining its economy and funding its military and terror activities. However, skepticism is advised regarding the transparency of Iran's published data on its oil industry.

Interestingly, oil prices are not soaring as one might expect. Iran's energy sites are relatively vulnerable, primarily located in the Persian Gulf and nearby Khuzestan province, close to the Iraqi border, home to a Sunni Arab population opposed to the regime (Ahwazi Arabs). The Iranian oil sector includes 10 major refineries, the largest in Isfahan, Abadan and Bandar Abbas, which produce a significant portion of the country's energy needs. In the Persian Gulf, Iran shares the world’s largest natural gas field, known as "South Pars," with Qatar. Any attack in this area could disrupt the global natural gas market, especially due to concerns about supply from Qatar.

Even in the extreme scenario where an Israeli attack halts Iran's oil production entirely, which is unlikely, the global market could absorb the impact. Oil producers have unused spare production capacity. Iran's neighbors and OPEC partners – Saudi Arabia and the Emirates – could, if necessary, quickly add 4.5 million barrels per day to the market to compensate for any loss of Iranian production. However, the proximity of these countries to Iran poses a risk. Should its oil facilities be attacked, Iran might retaliate by targeting the oil facilities of neighboring countries, disrupting the global oil market as it did in 2019 with Saudi Arabia.

Iran could also disrupt oil and gas supplies from these countries without firing a shot by attempting to close or mine the Strait of Hormuz. In such a case, the U.S. would likely intervene to keep the strait open. Since about a fifth of the world’s daily oil consumption passes through the Strait of Hormuz, any disruption would likely cause a significant, albeit temporary, spike in oil prices.

3 View gallery

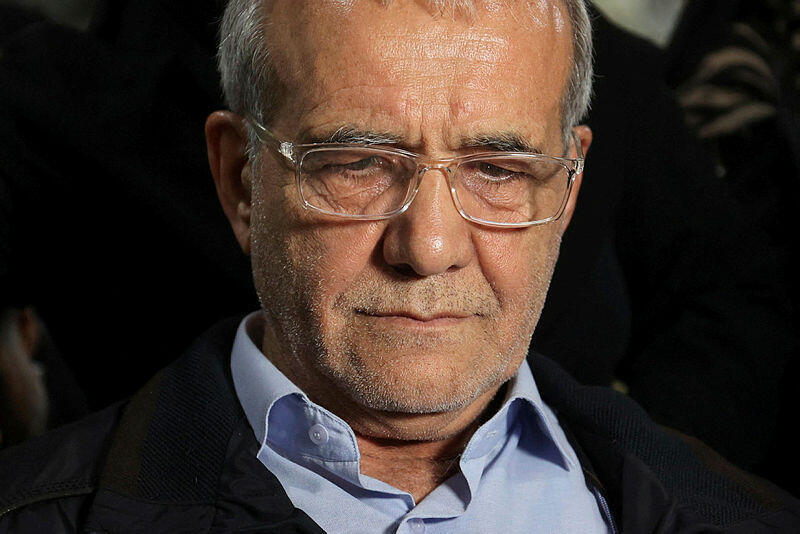

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian

(Photo: Majid Asgaripour/WANA (West Asia News Agency))

Overall, despite rising tensions in the Middle East, oil prices have not surged as expected, though they have risen since Iran's attack on Israel, and Brent crude trades around $80 per barrel, while WTI is about $76 per barrel. This price stagnation, despite instability in the region, is due to restraining factors, notably low growth trends in China and Europe, which are expected to reduce demand for oil. Another factor tempering price increases is the ongoing trend since December 2022 of strengthening the U.S. strategic oil reserves. The market anticipates that in an extreme scenario, the U.S. would use its strategic reserves to mitigate panic.

If Iran’s oil production is halted or damaged, China stands to lose the most. Currently, China is the main importer of Iranian oil, accounting for about 90% of Iran's exports, over 1.4 million barrels per day. Due to sanctions, Iranian exports to China operate through a "shadow fleet" of tankers that sail without activating their tracking systems and without insurance. Oil from tankers leaving Kharg Island is transferred to smaller tankers in countries like Malaysia, Bangladesh, the Emirates and Oman, eventually reaching China as if from those countries. Iran sells oil to China at a significant discount, saving China billions annually, and receives payment in Chinese currency. Due to the limited global tradability of the Chinese currency, Iran uses it to buy goods in the Chinese market or accumulates foreign currency reserves in yuan.

3 View gallery

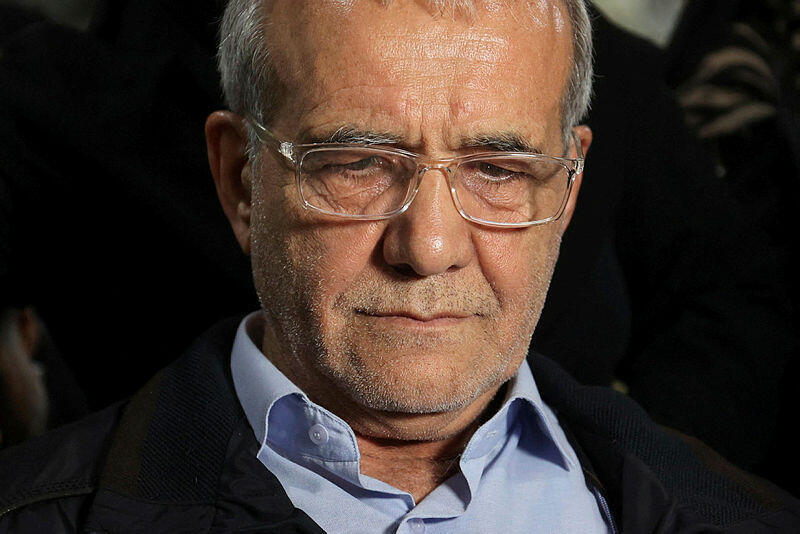

Chinese President Xxi Jinping meeting with Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

(Photo: Screenshot)

India, too, could face significant challenges if oil movement in the Gulf is disrupted. In recent years, India has reduced its oil imports from Iran due to international sanctions and a desire to maintain close U.S. relations. However, India's dependence on oil from the Middle East has only increased, with over 45% of its imports coming from the region. Any disruption in supply chains due to the Israeli-Iranian conflict could pose a temporary issue for India.

However, if Iranian production is removed from the market, there are potential winners. Recently, Russia has lost its status in the Chinese oil market to Iran. Kazakhstan, an ally of the Kremlin, could benefit from a disruption in Iran’s oil production. Kazakhstan has agreed to cut its production but possesses unused capacity of 1.4 million barrels per day.