Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

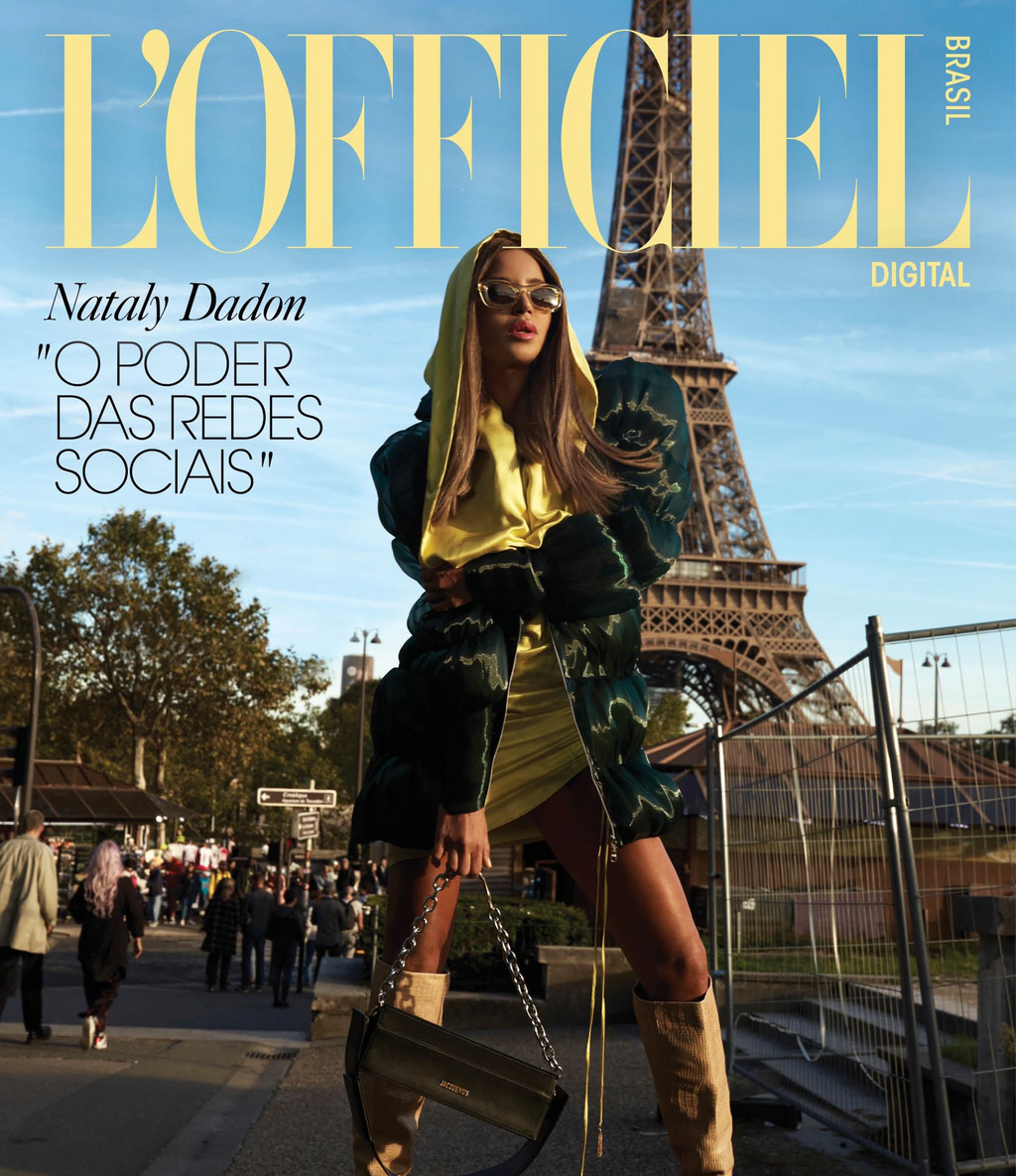

In the last month of January, Taylor Malkov appeared on the digital cover of L'Officiel Brazil magazine. Malkov is the latest addition to a lineup of local stars such as Nataly Dadon, Noa Kirel, and Yael Shelbia who have appeared on the covers of the international Parisian fashion magazine.

More Stories:

Featuring Israeli celebrities on the L'Officiel covers in Brazil and Dubai has sparked controversy in the local industry over the past two years. Nevertheless, we wanted to know - among the 220 million citizens of Brazil, who are those interested in Malkov and Dadon? And how much does Tanya Rayhelgauz, a wedding and evening gown designer from Holon whose name hardly rings a bell in Israel, make for dressing Malkov for the magazine cover?

Behind the scenes of these digital covers is the fashion entrepreneur Elad Borenstein, who has established his position in the industry over the past decade. He started as the partner and business expert of designer Idan Cohen, and is now the owner of "Brunnei" - a multifaceted fashion company he founded about three years ago.

Brunnei's goal is to provide designers with support in the processes of design, production, creation, and distribution of their collection, alongside the production of international covers for local clients, fostering collaborations between local designers and international companies.

The international covers produced by Brunnei receive acknowledgment on entertainment websites and popular Instagram pages, and generate a kind of systemic achievement that suddenly sparks interest in those celebrities. However, our investigation reveals that the digital covers are a commercial production with payment involved. In other words, unlike a normal cover produced by the magazine's editors and team, in this case, the cover is produced by the company Brunnei, and the designers whose garments appear on the cover, as well as the accompanying fashion production, pay participation fees.

Borenstein himself does not deny that these are commercial covers, but he denies that he or anyone on his behalf pays for them. Representatives of the magazines in Brazil and Dubai did not respond to Ynet's inquiries regarding how the models appearing on the digital covers are chosen and whether the magazine receives payment for their promotion.

"These are commercial productions, and the designer pays participation fees based on the garment," he explains. "The magazine receives the ready-made cover and production. However, we don't pay them, and they don't pay us. My goal is to match the star with a specific magazine."

What is their interest in publishing a cover with Nataly Dadon, for example?

"The talented candidate undergoes tests regarding her level of publicity and how active she is in what she does. With Noa Kirel, for example, we have another cover coming up soon for Eurovision, with the aspiration to have it featured in Britain's Vanity Fair or L'Officiel UK. We also expect a cover we produced for Lebanese star Maya Diab to be released in a printed edition, not just digitally."

And still, what does Malkov or an Israeli designer get from a cover in L'Officiel Brazil?

"There are brands that want access to new markets, and a brand that appears in such magazines earns prestige. An Israeli brand can dress Nataly Dadon at a sane price and receive a cover article along with an eight-page fashion production. It elevates them and their audience. Israeli clients love to see international success stories. I can tell you that with Idan Cohen, we hardly invested in domestic advertising - I always looked outward. The clients say to themselves, 'He's successful abroad' and they come."

It's showing off, essentially

"You call it showing off."

After all, for most Israeli designers, the clients are here, not in Dubai or Sao Paulo. If it were an international star I would understand, but who cares about Nataly Dadon and Taylor Malkov in Brazil? Even in Israel, they're not as famous as Noa Kirel.

"Now we have photographed model Elsa Hosk for the cover of Vogue Turkey, and we have started working with Lebanese singers Maya Diab and Myriam Fares, who sang the World Cup song. For the shoots with Diab, Dolce & Gabbana sent a dress, and they also paid. I will not impose an Israeli designer on Maya Diab, also politically speaking. It's not just commercial - we work to match each star with the right designer."

I'm still trying to understand why magazines need this. Is this their way of making money after COVID?

"What do you mean?"

The fact that you receive payment from participating designers, and two sources from the industry who are familiar with this confirmed the magazines were paid. After all, the magazines themselves sell digital advertising space for thousands of euros, even on their social networks, so why would they show such generosity?

"As I said - no payment is made to the magazine. And from their perspective, they receive a ready-made cover and production."

How does it work?

I go to Vogue Turkey and say to them, "We have Elsa Hosk for a photoshoot. What do you think?" If they give me the green light, we receive a letter addressed to the stylist allowing them access to the showrooms of designers. The magazine doesn't deal with production, but it does approve the inspiration board. It does not financially profit from it."

And the result is a digital cover?

The cover with Elsa is printed.

On Vogue Turkey's official Instagram page, it was clearly stated that the cover is "digital." How, then, can we find out the truth?

Borenstein is a charismatic and personally charming individual with a smooth tongue. However, he produces on steroids. Over the past decade, he has established a reputation for himself, as someone who stood behind fashion designer Idan Cohen, and together they presented as guest designers at New York Fashion Week, Paris Haute Couture Week, and dressed celebrities like Nicki Minaj and Jennifer Lopez.

His persona - as portrayed through years of professional familiarity with him and conversations we had with many people in the fashion industry who worked with and alongside him - remains enigmatic. On one hand, he tends to present things amorphously - even in this interview - with half-truths and unfulfilled promises. It is not surprising that some of the people we spoke to, who did business with him, requested not to be linked to him or the article. On the other hand, he has signed on to numerous professional achievements and is trusted by prominent figures and companies in the Israeli and international markets.

'I became an emotionless machine'

Borenstein (33) was born and raised in Givatayim, a middle child between two sisters. According to him, he was a hyperactive child who didn't have friends until a later age when he found his calling in therapeutic horseback riding and even competed in the sport. "I suffered from severe ADD. Today, I've learned to control myself, but as a child, I really struggled with it. It influenced my life," he says. "I was a kid from Givatayim competing with wealthy kids, and that had a significant impact on me."

Givatayim is not an underprivileged neighborhood.

"Yet, while everyone at the age of 17 had cars and jeeps, I cleaned the stairs for pocket money on weekends. That's how I was raised."

After completing his military service, Borenstein enrolled in law studies, but his life path changed when he met someone who would become his partner for six years: bridal gown designer Idan Cohen. Borenstein began working as a salesperson in a denim store at the Tel Aviv Port, which belonged to Cohen's aunt - Etti Levi. After a few months, he decided to join the bridal business.

"Within three days, I took over the business: I fired the saleswoman who was always sitting, and I sold the sitting area for three hundred shekels to an old man who passed by the street," he recalls.

The bridal gown industry is one of the most profitable and competitive in Israel. Designers such as Alon Livne, Lihi Hod, and established designers who are currently successful worldwide, like Berta and Mira Zwillinger, joined the ranks of the modern era of this enterprise. In order to establish themselves at the forefront of designers, they began working with Idan Cohen's brand, featuring the model Shiraz Tal as their presenter.

In February 2015, Idan Cohen presented for the first time at New York Fashion Week. In order to maximize publicity, Cohen and Borenstein chose to get married on the runway – a creative gimmick on one hand and a powerful LGBTQ statement on the other.

Did it contribute to public relations?

"Americans love such stories, and it became the talk of the town during Fashion Week."

How did your families react to the public wedding in front of the whole world? It's also a kind of coming out of the closet.

"In my case, everyone knew and accepted it openly. I was never that partying teenager who sneaks out on Friday nights and comes back on Sunday."

You're a bit like that.

"Not at all. I go to parties once or twice a year, and even then, I'm back home by two in the morning. I live a life of an old man: by ten at night, I'm already in bed, and by six in the morning, I'm already at the gym."

After the split from Cohen, the two continued to work together for about a year and a half until Borenstein chose to establish Brunnei. Today, the exes still maintain a professional relationship through Brunnei, which connected Cohen with the "La Premiere" network.

Regarding his departure from the brand "Idan Cohen," Borenstein says, "Idan is a fantasizer, and I am a workaholic. I turned into an emotionless machine. I blew up at people, spoke rudely, and became someone I didn't want to be. It turned into the good cop and the bad cop, and I was in the role of the bad cop who checks the finances because Idan is a pleasant person, and it's easy to fall in love with him. Automatically, I created a personality for myself that I no longer wanted. Maybe it suited me when I was younger, but I didn't want to be in that place anymore. During that same period, each of us had a new partner, and I felt like I couldn't hear about brides anymore."

Could it be that you wanted to be in the spotlight?

"I never minded being in the background, but when we separated, I didn't want to be 'the personal assistant' anymore."

You lived a lavish lifestyle: A Mercedes, luxury apartments, and brand names.

"I admit, I used to be more materialistic. Today, I am completely the opposite: I live in Herzliya and don't own a car. I keep my feet on the ground."

In 2020, Borenstein founded Brunnei as a business that aims to assist designers. The business model allows designers without a production background, or those who want to be designers, to purchase monthly retainers (ranging from 3,267 shekels to 12,900 shekels) for comprehensive support programs that include professional services such as logo production, collection building, branding, prototype tailoring, production, and social media management. According to him, the minimum quantity for producing a model is 30 units, which is ideal for young designers and celebrities looking to produce collections from A to Z.

12 View gallery

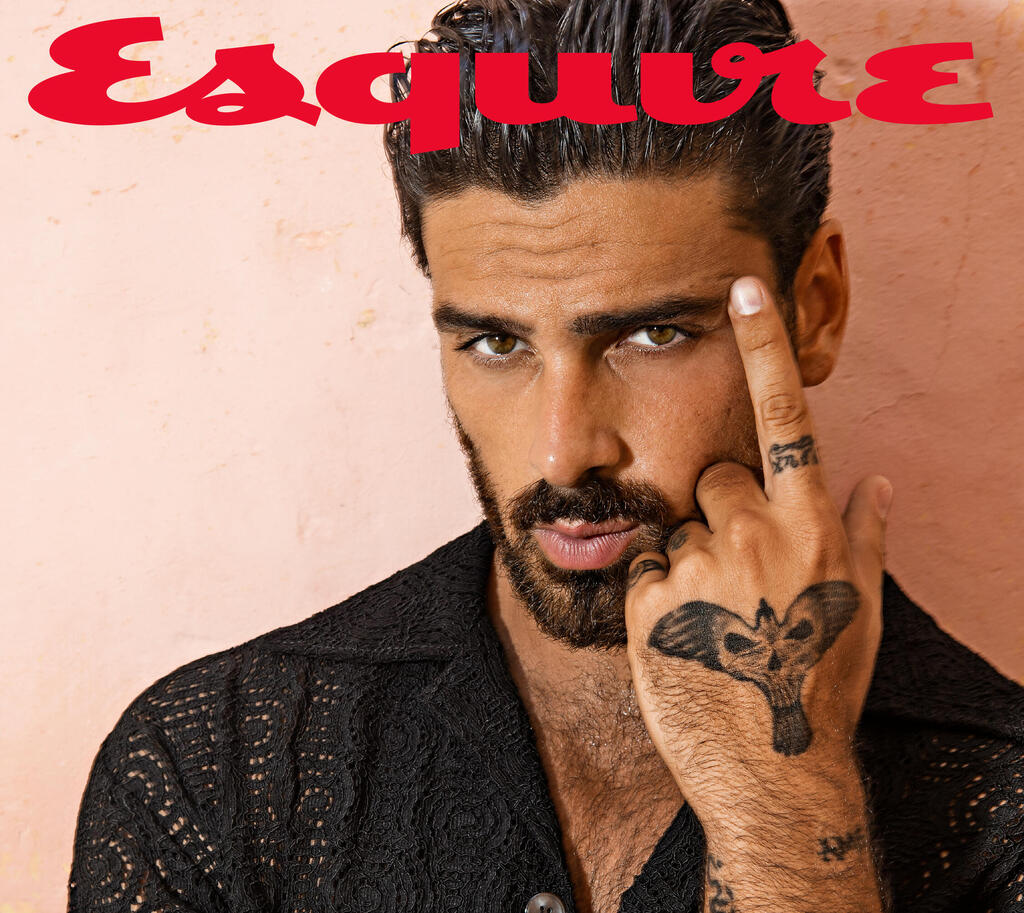

Michele Morrone on the cover of Esquire magazine in the production of Brunnie, 2022

(Photo: George Livieratos)

Let's say I'm an Instagram influencer and I want to start my own makeup line. How much would it cost me?

"It depends on the products. Gel eyeliners in two colors could cost around 40,000 shekels, while lipsticks range from 5,000 to 14,000 shekels."

'I thought Dubai was a place with high standards'

Borenstein's aspirations sometimes collide with reality. In October 2021, he initiated and organized the first Israeli Fashion Week in Dubai, an event he would surely rather forget. Despite the grand promises made to the media and the designers who took part, most of them from the Haredi sector, what will ultimately be remembered is a small event that looked like a deserted corner in a peripheral mall devoid of people.

"We were promised media coverage, a visit to an event with royal family members, connections with local salespeople and professional models," says one of the two designers we spoke with, who requested anonymity. "They brought us models from the street, most of whom couldn't even fit into the dresses."

Another designer present at the event in Dubai also complained, "They housed us in a hotel without kosher facilities; we didn't have a Torah scroll for Shabbat. We paid $5,000 for a booth at the fair, without additional expenses for hotels and flights. Bottom line: there won't be a second round in Dubai. People won't fall for it anymore."

When asked why they chose not to sue Borenstein or publicize it in the media at the time, they both replied that as individuals from the Haredi sector, they chose to drop it - "We're not people of conflict."

Borenstein himself grew uncomfortable when the subject came up, but took full responsibility and summarized the event in one word: catastrophe. "I had never been to Dubai before, and I just blindly followed my partners' stories," he said.

"I thought Dubai was a place with high standards. On one hand, I made history. On the other hand, it was the first time I did something without double-checking it beforehand. I felt ashamed. Those weren't the standards that I'm used to. I couldn't function for a whole month after that."

Did it embarrass you?

"All in all, I wanted to do good. I worked hard, I bent over backward for it, and I thought there was a production company in place. When I arrived, I discovered everything was on me, and I wasn't prepared for that. I'm not a production company."

But you produced it.

"I was responsible for bringing the designers. The contract wasn't with me but with the partners in Dubai."

No, the designers' contract was with you.

"No, I only received a commission for bringing the designers."

I spoke with several designers who participated in the event. All the dealings were with you, including the contract.

"I don't deny that."

The designers claim that the promises they received were not fulfilled.

"Each designer thought they would get a cover story. But buyers came, and some designers were offered entry into stores."

And what about the models?

"It was a catastrophe."

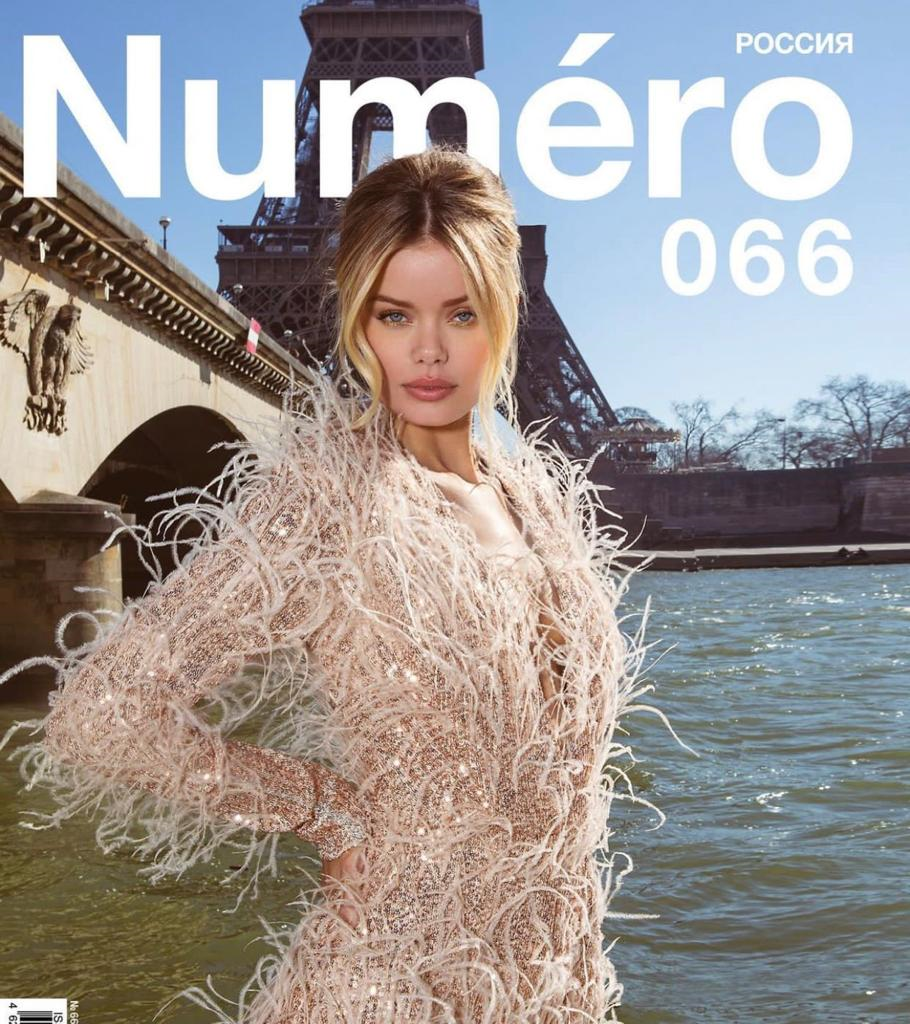

12 View gallery

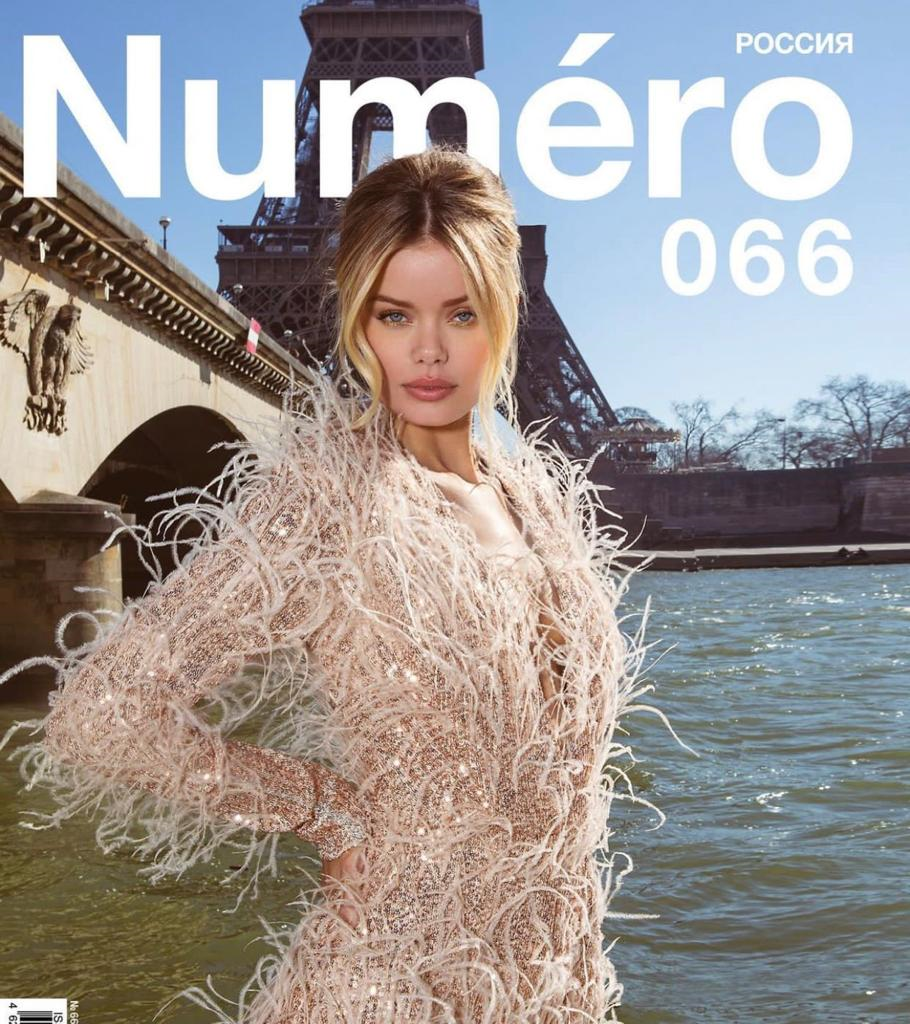

Frida Asen on the cover of Numero Russia, produced Brunnei

(Photo: George Liberatos)

Access to Dubai, which was granted to Israelis following the Abraham Accords, also allow him to work with major stars from the Arab world. According to him, as long as it is done professionally and without emphasis on Israeli women, there is no problem. "But there are clients who are bothered by it," he points out.

"We had a shoot with a Kuwaiti star who explicitly told us on set: No Hebrew. We were also in Dubai with Fairuz (a famous Lebanese singer) and we sat, laughed, talked, until it got to photos and social network posts together. There, the line is drawn, they don't want it documented."

So why do you still do business in Dubai?

"As a fashion entrepreneur, many local designers produce in Palestinian territories, such as Nablus, Gaza. But Dubai, London, and Paris don't have a Nablus and Gaza and someone who can produce a collection for them in two weeks. They have China, which is a longer and larger-scale production. As a business owner, I now have the option to provide them with development and production in a short time.

"They also understand fashion. When you mention Elie Saab (a Lebanese fashion designer, based in Israel) to someone from Dubai, she understands the high level and what I'm talking about. She saw someone wearing his designs at an event. For the designers here, it looks like just another piece of fabric."

Is there concern that the political situation will affect business?

"If so, we won't be here. I have no sentiments for the place. The company is registered in Israel, and we are in the process of opening offices in Dubai and Italy, for Arab clients who do not want to work with Israel. I am not here to engage in politics - I am here to work."