Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

We have a land flowing with milk and honey, at least according to the scriptures. It is blessed with wheat, barley, figs, pomegranates, olives and honey, and on our table one can also find yogurt, hummus, chraime and gefilte fish. Traditions from around the world, alongside Arab cuisine, have together formed a unique fusion here that birthed modern Israeli cuisine, but what is its original and primary source? Dr. Tova Dickstein has the answers.

More stories:

Israel’s foremost food archaeologist, Dickstein, specializes in the Jewish cuisine of the Second Temple, Mishna and Talmud periods. And it all began in New York.

"I lived in Manhattan for four years and one day, while walking down the street, I suddenly smelled roasted eggplants that reminded me of my childhood, even though my mother is originally from Transylvania," she recalls the moment she started to investigate. "When I looked up, I realized I was standing next to a Lebanese restaurant, which raised a lot of questions for me."

Her journey into the world of Israeli cuisine lasted ten years, and included the recreation of 200 recipes from the Bible, research of Greek and Roman sources, and culinary archaeology. The result was a Ph.D. that examined the new Israeli kitchen through its roots.

Our ancestors' food

According to Dr. Dickstein's research, 3,000 years ago lentils and birds were widely eaten here. Pigeons, turtledoves and quails were most popular before chickens were introduced. She also found that apples were believed to help build your strength, and roasted and ground lentils with honey was comfort food. You're probably raising an eyebrow at this description, but translated into today's terms, we're talking about tasty pancakes made from lentil flour with added honey.

One of the most popular snacks in ancient times (and the first food found in excavations in the Jordan Valley) was called "makhana". Today you can find it in Indian stores, and it resembles a cross between popcorn and giant puffed rice. Another snack that was commonly eaten was called "gebs kolo" - roasted barley grains that can be found today in the Ethiopian kitchen as a nibble after the coffee ritual.

Meat was typically consumed only during festive events due to the lack of refrigeration methods. "Calves symbolized happiness and wealth and were only eaten three times a year, during pilgrimage festivals and family celebrations," Dickstein explains.

Because of refrigeration difficulties, the only cheese our ancient forefathers produced was kishk cheese, or what is called today yogurt “stone” hard cheese. Yes, that trendy yogurt stone which in recent years has shifted from the Arab kitchen to dozens of chef restaurants, considered by many to be an exotic seasoning, is actually the first cheese produced in Eretz Israel, and it is mentioned in the Bible.

Other products mentioned in the Bible and still found today in the Arab kitchen include samneh - the clarified butter that forms the basis of good baklava, and zabadah - sweet cream.

As meat was expensive and difficult to store, it was replaced by legumes and grains, exactly what today provides us with a serving of falafel in pita bread or mujadara. The most mentioned dish in the Mishnah is ful (fava beans), and the food found most often in archaeological excavations is lentils.

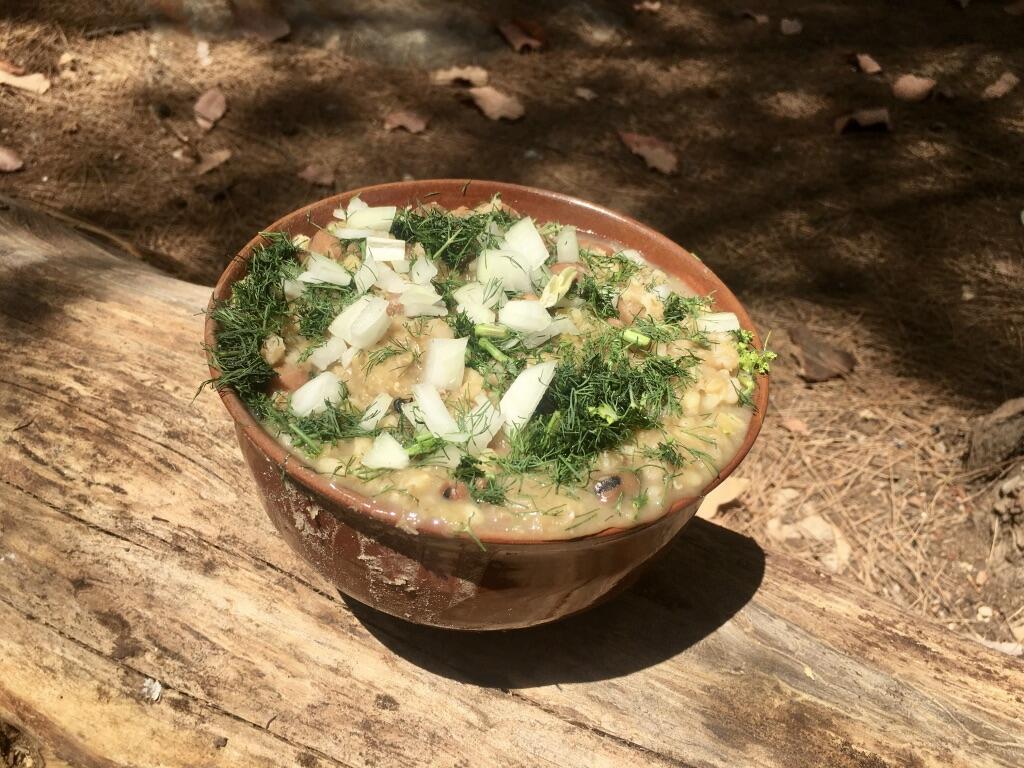

This is likely because the national dishes of ancient times were fava bean and lentil stews, and fava bean spreads. The Book of Ezekiel mentions a dish named "bread," which is in fact a lentil and legume stew, a twin dish to "flicaria" from the cuisine of the Greek island Crete. The fava beans were cooked with olive oil, mint and garlic. In Morocco and Egypt, you can find this dish today under the name "bissara."

Fish were also occasionally consumed - fish bones from the time of King David were found in archaeological excavations in Jerusalem. And what about dessert? A sweet dish named "saliyah" that contained wheat, sugar and cinnamon, and today can be found in Turkish and Lebanese cuisine.

Gourmet food

Lentils, fava beans, stews and dishes are all fine, but what did the wealthy eat during their lavish meals? Evidence shows the consumption of locusts marinated in broth, peacock tongues in mustard and an ancient type of stew made of wheat, lupine and onions. Evidence of a festive fish dish has also been found, which has transformed into the modern-day gefilte fish of Ashkenazi cuisine and the spicy fish stew (chraime) of Middle Eastern cuisine.

In biblical times, festive fish dishes were typically served with leek, either over it or filled with it. "Speaking of fish, it's worth mentioning that there's a reference in the Mishnah to a dish of fish in batter, essentially an early version of fish and chips. This likely made its way from here to Portugal, and from there to England," explains Dr. Dickstein.

Wheat and bread

The original wheat of Israel is durum - a wild wheat that was cultivated here until the 1940s and is currently being reintroduced for use in some boutique bakeries in the country.

According to Dr. Dickstein, it was replaced due to the demands of immigrants. "European immigrants were looking for soft bread, which was difficult to make from this wheat, even though this wheat is best suited for cultivation in our region as it is resistant to all genetic diseases and can grow even in high temperatures."

To meet the demand for soft bread, a method was developed in Israel that enables the growth of regular wheat under Israeli climate conditions, and the native Israeli wheat was pushed aside. And what about bread? The matzot of that era were identical to the bread that can be found today in the Bedouin settlements in the Negev, which is baked inside the hot coals of the campfire after the fire has been extinguished.

Spices and wild vegetables

Seasoning was primarily done with plants such as coriander and mint, but garlic and cumin were also very common. Hyssop, which is today more commonly identified as za'atar in Arab cuisine, was considered in ancient Israeli culture to be a plant with purification properties and the ability to ward off death.

Talmudic literature mentions wild vegetables such as orache, and in the Book of Job, one can find mallow. Today, Arab, Druze and Bedouin women gather these plants to add to dishes.

"Foraging, which today is associated with indigenous food cultures like Arab cuisine, was part of the cultural and medical values of the Israelites in ancient times," says Dickstein.

Her research shows that many characteristics of Arab cuisine are also features of the indigenous Israeli cuisine, which may perhaps put an end to the debate undertaken by the global Slow Food movement (which currently has no official representation in Israel) regarding "what is the original food of Israel."

Other cuisines that still use elements of biblical culinary arts today are the Ethiopian and Yemeni kitchens, likely due to the careful preservation of cultural traits among Jewish populations in these countries.

"Food is both a longing and a means by which we connect to our roots, touch the past and shape the future," says Dickstein. "My research, which for me was a mission, clearly shows that our culinary past is identical to the culinary present of the Arab population living in Israel and our neighboring countries."