Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

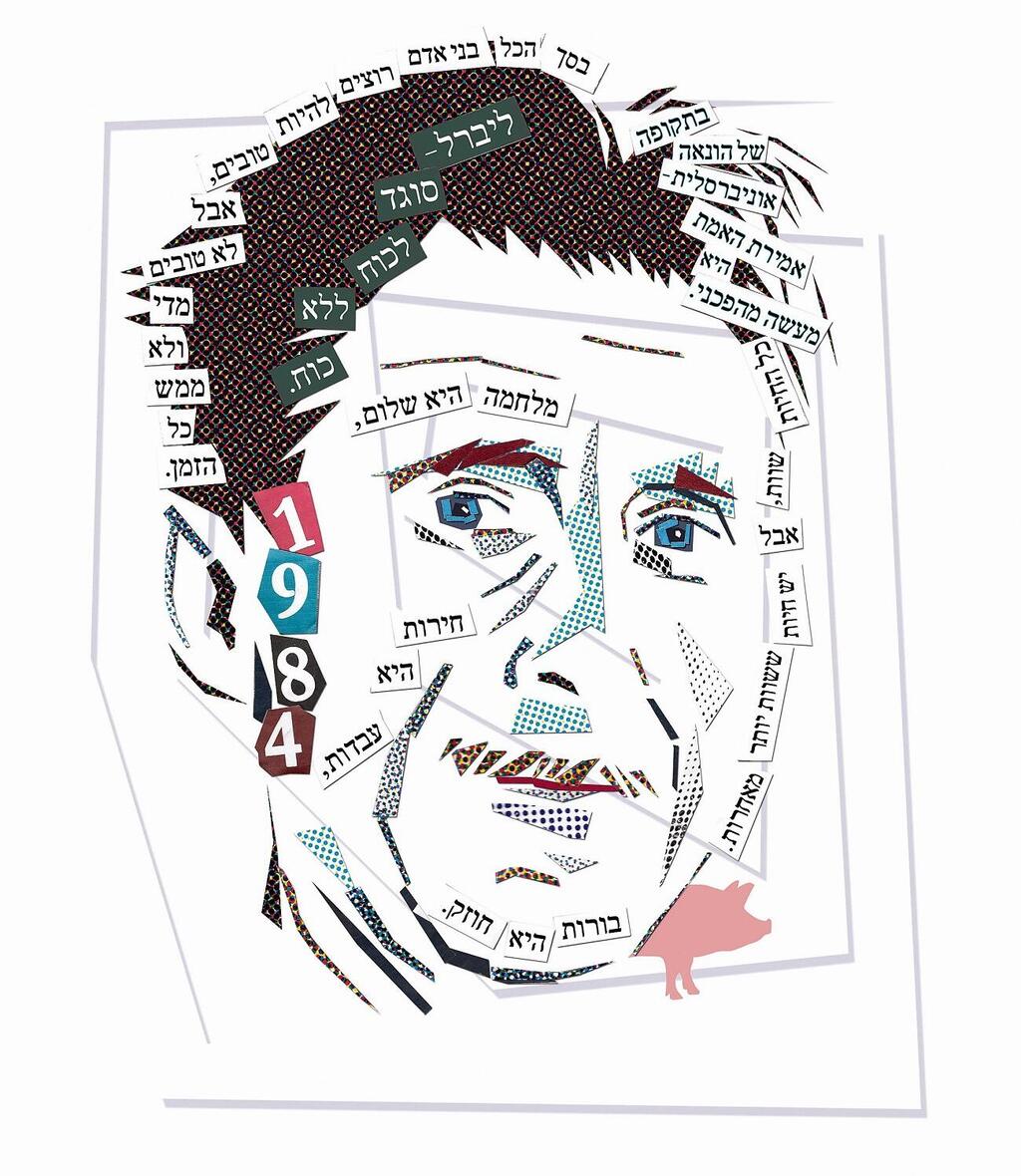

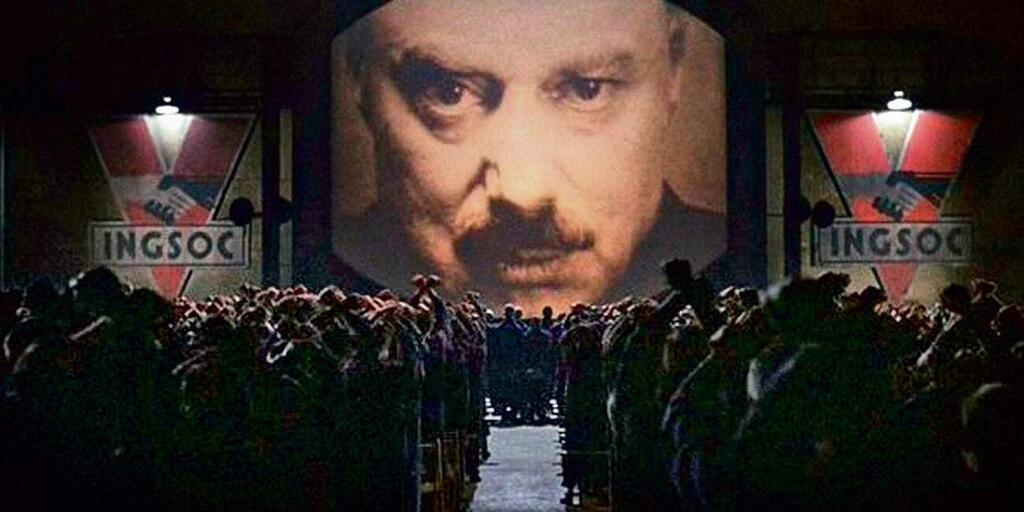

Weeks after Donald Trump's victory in the U.S. presidential election, Amazon announced that sales of 1984 had increased by 700%. 66 years after George Orwell's death, it is still a bestseller. His books, especially the last two, Animal Farm and 1984, have been adapted into various forms of media, and their readers are convinced that the hidden truth in them still shines for each of us, warning us of the consequences if we fail to preserve our freedom.

Read more:

Circumstances have changed, and the threats seemingly passed, as Stalin and his heirs were removed, and the fear of totalitarianism from the right also waned. However, the terror of a dreadful world, where the pigs rule and truth is a lie, still lurks in the shadows, plotting its return.

The fact that Trump breathed life into this terror was evident to Orwell's admirers, who claimed the truth, even with the book's publication in the mid-1949. They saw that Orwell's harsh dystopian message goes beyond focused criticism of the communist regime of the Soviet Union, extending to all oppressive, deceitful, and destructive regimes. So, they ask, what is the difference between the manipulations of truth in Big Brother and the fake news of the Miami liar?

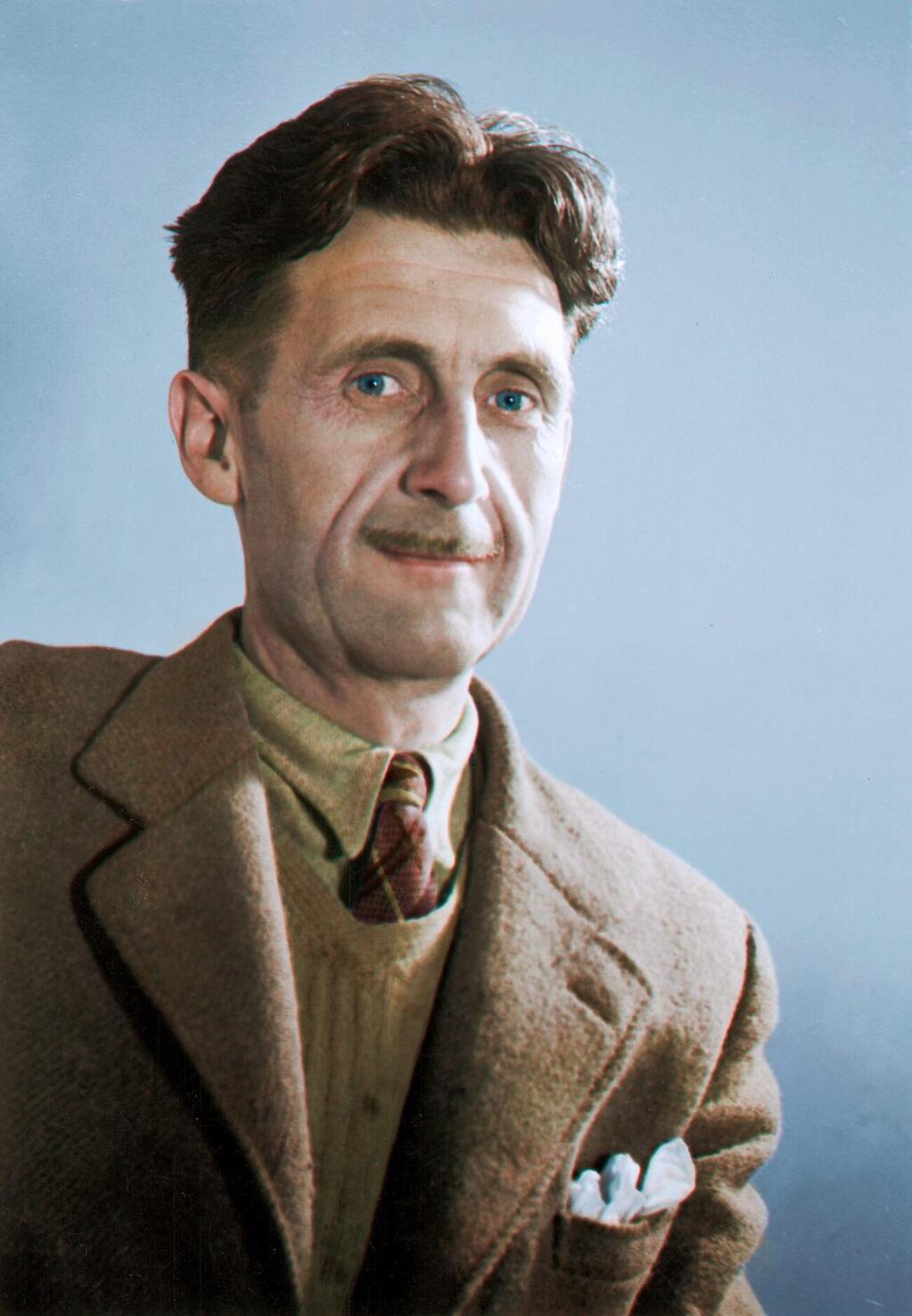

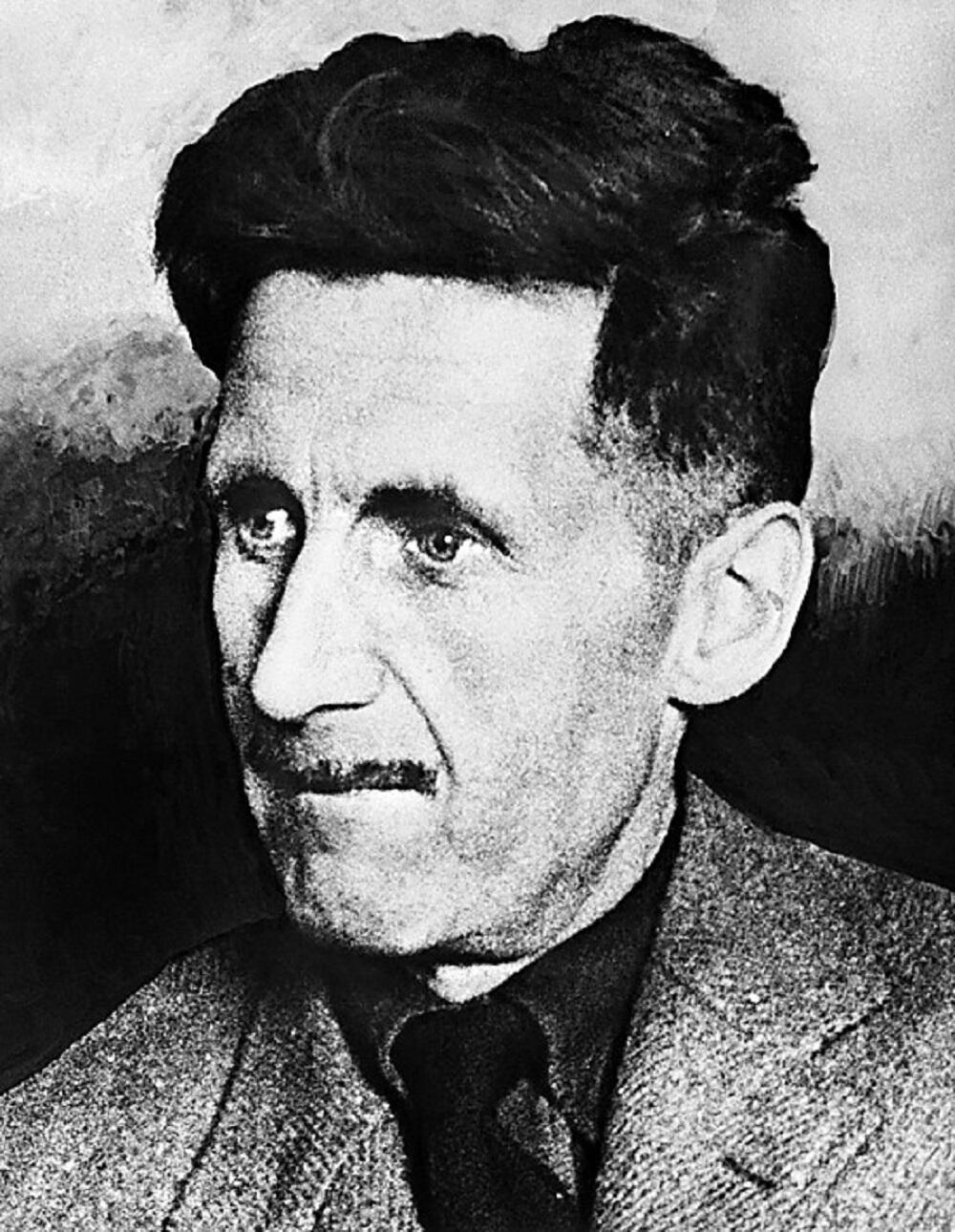

George Orwell is the pen name of Eric Arthur Blair. His life story and relationships with associates and friends testify that he did not hesitate to criticize harshly and mercilessly. Even writers and critics who saw him as a close friend reported that he didn't hold back from visiting strong criticism on them.

The fear that haunted Orwell was that he might not be considered a man of truth. He had enemies and critics in both camps. Left-wing people, especially radicals and communists from the rank and file, appreciated his alignment with the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, but accused him of sympathizing with the fascists when he criticized Moscow's takeover methods on the rebels.

The left adhered to strict doctrine and a system of laws to which one had to adhere even when doubts arose. The possibility of being branded as one who deviates from the line was its greatest fear in life. This left did not buy Orwell's historical explanations and those of his supporters.

Several important editors and respected publishers in Britain rejected 1984 because they interpreted it as a blunt attack not fitting for the Soviet Union, the brave ally in the fight against Nazism. The radical left interpreted the book as a stab in the back of the progressive revolution and freedom.

Stalin's followers believed that the miniature tyrannies of suppressing freedom and thought control were a clear sign of a writer indulging in delusions, someone who couldn't grasp that the promised spring of the peoples is of great significance compared to travel fares to be paid along the way. They mocked and said that long before 1984, Orwell's predictions would prove to be the hallucinations of a pretending left-winger. They were wrong.

However, Orwell had detractors and enemies from both the left and, especially, among the ideological conservatives. They couldn't understand how a man from their own class, a graduate of the elite Eton school, could connect with the working class and the uncultured proletarians.

His last two books somewhat changed the balance of positive and negative reception. On the left, only the tone and resistance increased, while on the conservative right, they embraced the man as one of their own who insisted on appearing like a proletarian.

Animal Farm was an immediate massive hit upon its release, and his publishers struggled to keep up with the demand. Queen Mary, the widow of George V, sent her people to purchase the book, but when they returned empty-handed, she instructed them to look for the book in the anarchists' bookstore. Winston Churchill's doctor reported that when he came to visit his patient, he saw 1984 in the bedside cabinet next to him.

Interest in Orwell did not wane even decades after his death. It's hard to say that he achieved the status of one of the most important writers of the 20th century solely due to the quality of his work. Even among his contemporaries in Britain and beyond, there were other writers whose creations were appreciated more than some of Orwell's works.

Over the years, the perception of his entire body of work has changed. He wrote extensively for the press, and among the 20 volumes that comprise his complete works, many discover articles, book and film reviews and philosophical musings on social and cultural matters that are literary gems.

Until his involvement in the Spanish Civil War and the book he wrote about it, Homage to Catalonia, George Orwell was a rather marginal writer. The books he had written until then did not arouse interest, and among his few readers, he was known as a sharp critic of the social situation in his country and of colonialism. His five years of service in the Burmese police, his experience of poverty in France, and his exposure to the lives of workers and miners in his country were the sources from which he drew his creations.

The few who knew that George Orwell was Eric Blair, who studied with them at Etonz, couldn't understand what happened to him. However, Eton and the social class that sent its sons to prestigious schools were accustomed to occasional deviations that emerged from their midst. They forgave him, but were shocked when they realized that he was not content with social criticism and had something to say about the world in which we live.

His experience in the war in Barcelona, his awareness of Moscow's methods toward other Republican factions that did not bend to its will, changed Orwell's world beyond recognition. He broke the boundaries of the British establishment and entered the larger world. As a result, he encountered even harsher and more ruthless enemies among his right-wing colleagues.

The radical left, which struggled to acknowledge its defeat, did not miss even a trivial opportunity to remove the "righteous" crown from Orwell's head. They tried everything, including information that lacked substance, claiming that the author, from his sickbed from which he never rose, had sent a detailed and organized list to British intelligence of all the communists he knows. When the letter Orwell sent to his friend, on which his accusations were based, was published, it became clear that it was not a dangerous denunciation by someone with communist tendencies.

Another Orwell biography?

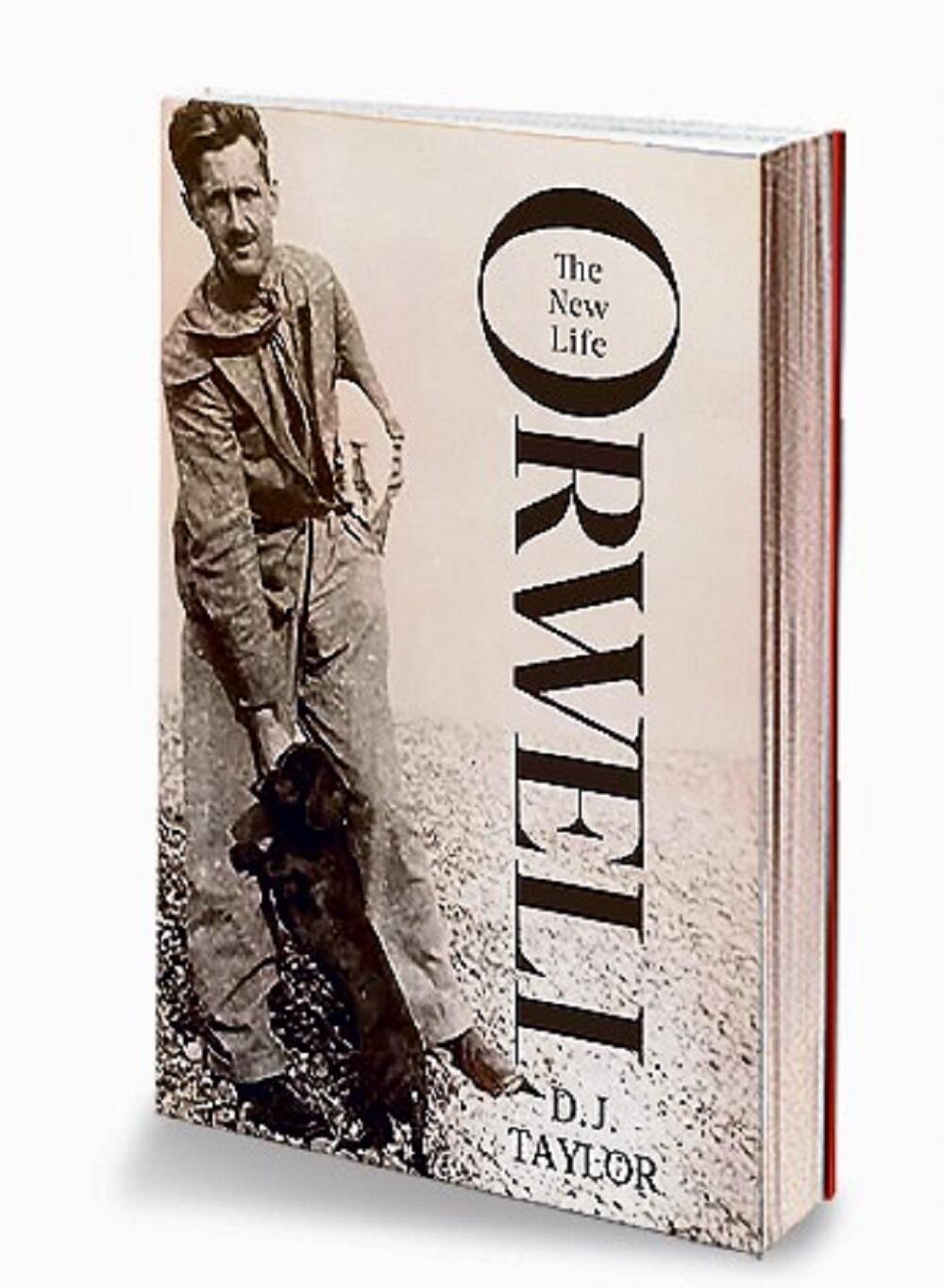

The New Life, Orwell's latest biography, is the second book written about the acclaimed English author by the renowned biographer D.J. Taylor. The first book was released in 2003 to critical acclaim.

Taylor was not the first or only biographer of Orwell. In 1980, Sonia Brownell, Orwell's second wife, commissioned Bernard Crick, a left-wing researcher, to write her late husband's official biography, a task well-deserved given the scarcity of evidence and documents at his disposal.

The widow, who married Orwell a few months before his death in a sanatorium, did not withhold her opinions about him. After Crick, the race began: who would write Orwell's definitive biography. Many candidates emerged, including Taylor, who published his work 20 years ago. Now, he returns to the endeavor and offers readers further improvements.

Writing a second biography about a figure already thoroughly covered in a comprehensive book is indeed a rare phenomenon. It's important to emphasize that Orwell: The New Life is not a revised and corrected edition of an old work but an entirely new composition.

Should we interpret the decision to revisit Orwell as an acknowledgment of failure in the first attempt? How does Taylor explain his choice to devote three additional years to the life of an author who has already been extensively written about? Perhaps he was enticed by the hope that marking the 120th anniversary of Orwell's birth in these days would rekindle interest in him and his writings.

Taylor's first response is technical in nature. Since the publication of his first book, an abundance of new evidence and documents have come to light, shedding a new and more intricate light on the author's life and work. To those wondering if every time new documents are revealed, Taylor will write a new biography, he responds that the possibility of uncovering new evidence and testimonies is non-existent after more than 70 years since Orwell's death. No one remains who had the opportunity to know Orwell during his lifetime and share firsthand accounts.

The second reason for the effort is more complex. There is nothing new to be discovered about Orwell's life story, but our current times have set the stage for a fresh examination of his legacy. As we mentioned before, the surge in sales of 1984 followed Trump's election. Orwell's new readers find messages in his work that didn't catch on with the readers of the 1950s.

The updated examination of testimonies, especially letters, diaries and memoirs of those close to him that have emerged since the writing of the old biographies, significantly diversifies the portrayal of the author, removing the aura and greatly enriching the understanding of the connections between his life and work.

The story of certain aspects of his life and relationships with his contemporaries attests to the depth of contradictions between the image he crafted for himself, seeking to present it to the public and his readers, and the essential traits of his character and conduct.

Taylor's aim is not to dismantle idols but to render his protagonist more human and complex. The New Life indeed presents a fresh, more intricate, and more human personality. We will now shed light on certain aspects of his character as they emerge from the updated examination.

Post-Holocaust shift in attitude

More than anything, Orwell loved concealing his social background. He didn't spare any opportunity to denigrate, mock and undermine the foundations of class perceptions prevalent in English culture.

For this purpose, he downplayed his appearance, smoked cheap and foul-smelling cigars, and displayed nonchalance whenever he sat for a pint of cheap beer, naturally in the workers' and industrialists' pubs. He declined invitations to socialize with his fellow Etonians in cafes and fancy restaurants where his kind would spend their leisure time.

However, Orwell couldn't deceive anyone with his disguises. He was often taken aback when he encountered a factory worker or a miner in one of the workers' pubs, and the waiter addressed him as "Sir." The waiter didn't buy Orwell's act; he knew that anyone seeking his service was a "gentleman" in every respect. The hat might be taken off, but it's challenging to shed the accent and the affected speech of an Eton graduate.

In several of his significant and insightful articles on the class structure that distinguishes life in Britain, Orwell attributes a crucial role to the educational institutions he attended. His articles on youth and youth culture in his country bear witness to the sharpness of his abilities and his vision.

Taylor reminds his readers, what he didn't do in his first book, that when Orwell adopted his son Richard, a newborn baby, he wrote with great enthusiasm about the dramatic change in his life and the purpose of the education he would invest in him: to prepare him for admission to Eton.

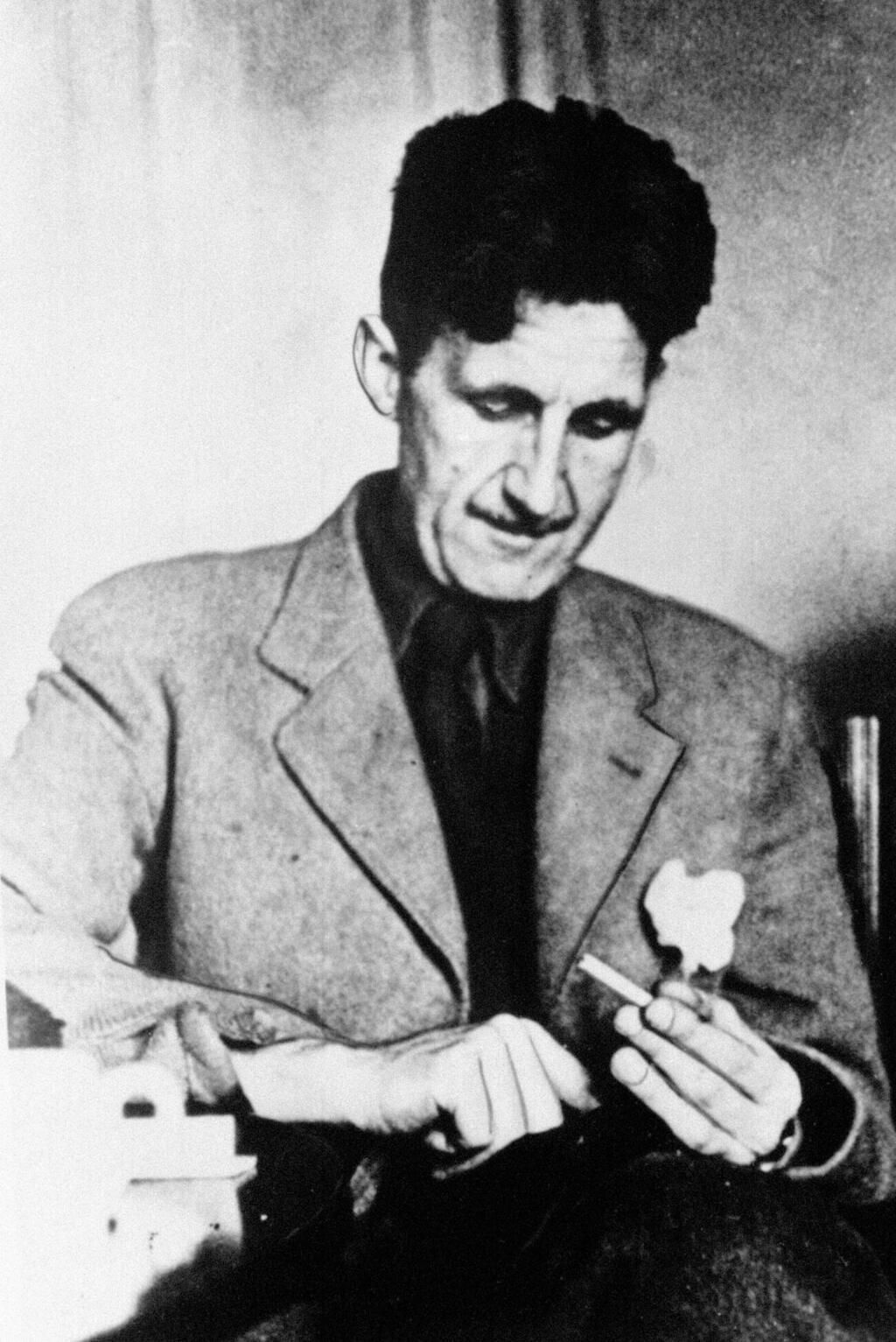

Orwell married his second wife just a few months before his death. His first wife passed away a couple of years before him, and when examining his relationships with women in his life and women in his books, Taylor argues that a consistent pattern emerges: Orwell greatly loved women and didn't hide his affection for them.

From the letters he sent to his beloveds, which are presented in the book, the author is revealed as a man "who won’t take no for an answer." He didn't demand much from the women he proposed to; he was even willing to forgo regular sexual relations as long as the potential wife assured him that she knew how to serve him. He didn't hesitate to address his correspondents with this explicit question.

As for his second marriage, there is no clear explanation. Why did he marry knowing that his imminent death was unavoidable? Why did Sonia Brownell agree to marry him? Any speculations about these dilemmas do not provide a clear answer. It’s hard to expect another biography to clarify this matter.

Orwell's comments on gender and sexual orientations did not endear him at all to LGBTQ+ community readers. He could not tolerate homosexuals or any behavior deviating from the accepted norms of gender and sexuality in the society in which he lived.

He saw homosexuals everywhere. The restrained and composed writer lost all measure of reason when he wrote about them in his diary. He didn't hesitate to affix all the derogatory definitions and terms prevalent in the colloquial English language to them. "Queers" was the mildest word in his vocabulary.

Taylor tries to convey to his readers that they should show some leniency toward these outbursts of Orwell; after all, Orwell was a product of his time and culture. In the days he was writing, homosexuals were thrown into prison. Yet, he wonders, given our understanding of the atmosphere and the relationships among the students and their teachers in their educational institutions, is there any escape from questioning which demon Orwell is fighting in his attitude toward homosexuals? Taylor resorts to Shakespeare and asks his readers if it is possible that Orwell doth protest too much with his animosity toward homosexuals.

Isaiah Berlin once said in one of his wise insights that in England, where he lived and was familiar with its spirit and culture, an antisemite is someone who hates Jews more than is necessary. Even in this domain, Orwell was thoroughly English. The reading of his diaries is quite embarrassing.

The writer, who described in great detail the dreadful world awaiting humanity, resorts to the most ignorant stereotypes when writing about Jews. As expected, Jews, in their supposed cunning, are present in every moment of decision-making.

When he encountered a pushy and uncultured woman during one of his journeys on the subway, he immediately attributes "Jewish" characteristics to the woman being pushed. It is beyond belief that an Englishman, or for that matter, an Englishwoman, would not follow the etiquette of standing in line. Everyone knows that the English respect queues, so she must be Jewish.

In the years following the war, Orwell wrote for the left-wing magazine Tribune. The newspaper's founder and first editor was Aneurin (Nye) Bevan, a left-wing icon in Britain, minister of health in the Labour government, and the founder of the National Health Service (NHS). Bevan supported Zionism and its aspiration for an independent state in the Land of Israel.

Orwell, a member of the Tribune team, was invited to participate in a discussion to determine the newspaper's stance on the issue of Israel. Bevan wholeheartedly supported the encouragement of the Zionist idea and lavishly praised the Zionist enterprise.

He was assisted by another editorial team member, Tosco Fyvel, a close friend and dedicated supporter of Orwell and a Zionist activist. Orwell vehemently opposed the proposed editorial line; he claimed that the whole matter of Zionism is an invention of Jews who control the mainstream media.

Tosco Fyvel, in his memoir about his close friend, writes that after World War II, and especially in the light of the Holocaust, Orwell became very cautious about his stereotypical remarks about Jews and refrained from making them. Taylor reminds his readers that Tosco Fyvel rushed to exonerate Orwell from this offense. Many years after the publication of 1984, the manuscript of the book fell to the hands of researchers. They were not surprised to discover an antisemitic remark that did not serve the needs of the text. Orwell likely erased the unnecessary remark himself.

Contrary to others who were antisemitic, even though they had never encountered Jews, Orwell met and knew many Jews. Some of his closest friends were Jewish. One of his closest confidants was Malcolm Muggeridge, the journalist and intellectual who was a communist in his youth but later became an opponent of communism after an extended visit to the Soviet Union.

After attending Orwell's funeral, Muggeridge wrote in his diary that he was very surprised by the large number of Jews present at the church and cemetery.

Both of his literary executors in Britain, Victor Gollancz and Frederic Warburg, were Jewish. Arthur Koestler, with whom Orwell collaborated on various international peace organizations, was Jewish as well. He was certainly exposed to a large dose of positive Jewish traits from John Camachi, the writer and editor of Tribune, with whom he shared an apartment during his bachelor days in London.

Therefore, it is difficult to draw sweeping conclusions from these remarks about Orwell's attitude toward Jews. Like many Englishmen of his generation and social standing, he may have harbored some occasional prejudices against Jews, but no more than that.

The 1984 enigma

We are left with the enigma and vitality of the work 1984. During the years he wrote the book, in the last years of his life, Orwell took a great interest in dystopias and futuristic horror novels. His friend, Piotr Strobel, the White Russian exile who lived in Paris, told him about Yevgeny Zamyatin's book We. In his diary, Orwell wrote that he had looked everywhere until he managed to obtain an English translation of the book. Zamyatin ventured into distant worlds, and his book was filled with different kinds of robots and electronic creatures that take over the world, as befits the tradition of futuristic literature.

According to Taylor, 1984 has enjoyed a long life and an enduring influence precisely because it avoided soaring into imaginary worlds. Readers of the book were struck by fear and dread precisely because Orwell rooted his characters and plot in a recognizable contemporary reality, where one could easily identify the seeds of the terrifying world we are marching toward.

The landscapes of his book are the streets that the reader knows, and no effort of imagination is required to predict the demonic power of authoritarian leaders. In the newspapers of 1948, many leaders who could become the Big Brothers of 1984 shone.

The corruption of language is a hugely significant factor in the terrifying world that Orwell describes. Readers of the book in 2023, 74 years after its publication, will require very little effort to prove that this plague has not yet passed. In a world where people are not deterred from dismissing claims of "alternative facts," and "Big Brother" is the name of a popular TV show worldwide, Orwell remains relevant. It will not be surprising if, in a few weeks, an announcement from Amazon indicates a substantial increase in sales of Orwell's books as the world marks 120 years since his birth.