Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

A tour of Sombor, Serbia - Nikola Jokić's hometown

(Video: Zeev Avrahami)

"When Nikola arrived here in ninth grade at the age of 15 in 2010, he was already two meters tall and, if we're being polite, a bit chubby and very clumsy. He couldn't even do a single push-up, and he couldn't jump over the vault in gym class. But he didn't complain about it like a petulant child who doesn't want to do something; rather, it was more like a cry for help. You know, as big as he is, he's also gentle. So he suggested that instead of push-ups, he would do double sit-ups and help all the other kids. We don't know how many sit-ups he actually did, but we're sure of one thing: in the two years he was here, no one fell while jumping over the vault," according to Nikola Jokić's former gym teachers.

Read more:

Valerija Forgić, 47, and Marija Lukić, 53, were NBA champion Nikola Jokić's gym teachers when he studied in grades 9-10 in his hometown of Sombor, Serbia.

They remember how he stretched his legs in the front row, making it impossible to open the door, and how if he folded his legs, his desk would go up in the air.

Everyone wanted to be around him because laughter filled every place he went, but never at the expense of others. He took the blame for children who were afraid to admit something they had done. But he was shy with girls.

"I was his volleyball teacher," says Lukić. "He always stood out because all he wanted to do was play with a ball. It didn't matter what kind. The joke among his neighbors was, 'You don't see Nikola, you hear Nikola.'

"Water polo, dodgeball. Just let him play. He always had a very high intelligence that compensated for his lack of physical fitness. He came to me and said he wanted to play volleyball, even though he knew nothing about the sport. I told him it was no problem, just go and train for a week. After a week, he came back and fit right in," she says.

"When he became famous, he came here one day, stood behind me, asked my students not to tell me he was here, started making funny faces, grabbed my head from behind, and gave me a kiss on the forehead – then went to practice his shooting. After that, we sat down and he told me that he came to me to ask to play volleyball because he had watched several school team games and realized I lacked a good center and a shot blocker. And that's what he became," Lukić continues.

But those are roles that require agility.

"Don't get the wrong idea. Nikola can jump, but why jump if you can solve everything with positioning and footwork? To understand Nikola, in basketball and in life, you need to remember a very important fact: You and I see the world in frames. He sees everything in the big picture," his former teacher says.

"Volleyball is the decisive part of Jokić's life, much more than basketball. We'll come back to it.

"When Nikola comes here in the summer," says Lukić, "there's always a deal: a whole month we can bother him, ask for autographs, pictures and then we let him be a regular citizen. He comes to the pool, plays beach volleyball and basketball on an open court with locals, goes to the club, dances, invites everyone for drinks, visits the horse farm.

"Once we played beach volleyball by the river, and a large group of girls approached him. Nikola stopped them and asked what they wanted. They asked for an autograph. When he finished signing, he asked them, 'But what do you really want?' And they gave him a shirt they had made for him."

How did he know?

"Nikola is a fantastic basketball player. He always learns everything quickly. Everything we taught him, he understood the first time he practiced it. But his greatest attribute, far beyond basketball, is how he understands people, what they need at that exact moment. A hug, a kind word. Nikola is metaphysical. He reads people. He is a perfect person in our eyes, almost godlike. He just doesn't promote it because he is humble," according to Lukić.

"The job is done, we can go home now," Jokić said in the post-game interview last week after winning the NBA championship with the Denver Nuggets, the first title in the club's history. When he was informed at a press conference that the championship parade would only take place on Thursday, the Finals MVP expressed his frustration and exclaimed, "No, I need to go home." There was a big horse race scheduled in Sombor, and Jokić had to be there.

"Despite his guarded nature, Nikola is an open person. He doesn't say one thing and mean another," says Coach Forgić. "When he proudly holds his daughter's hand during the trophy ceremony, it speaks volumes. It reflects his priorities. When he talks about home, it's a heartfelt statement. Denver is his workplace. He came, did the job, and returned. Home is here. The language, the family, the homeland, nature, friends and clubs. That's where he recharges."

"We met in the past after he was named the MVP of the season. I asked him about basketball, and he brushed me off, requesting that we talk about our children instead. The beautiful thing about Nikola is that if you know him, you understand that all his basketball is an X-ray of who he is on the inside. Everyone says Denver relies on Nikola, but that couldn't be further from the truth. Nikola relies on Denver, both the city and the team, much more than the team relies on him," she says.

'He's not as stubborn and macho as his brothers'

Sombor is a small town located about two hours north of Belgrade, on the tri-border area with Hungary and Croatia. There are "60,000 residents and everyone greets you and asks how you're doing," says Sandra Papo-Fišer, 45. "Everything is calm and peaceful. If you want to talk to someone, you don't send a WhatsApp message; you invite them for coffee and cake. It's the city with the most trees in Eastern Europe. Originally, I'm from Belgrade. I met my husband in Hungary when we both fled the bombings of NATO, and we got married after five months."

"I've been here for over 20 years, and at least once a day I feel like exploding from how kind and calm people here are. Men just want to help around the house and cook and enjoy family meals. They don't have any spice. I love it, but once a week, I need to escape to Belgrade to calm myself with a bit of chaos. If you understand that, you can understand Nikola and how this place is a reflection of his character, his compassion, and empathy," she explains.

Fišer and her husband are part of a Jewish community of 50 people in the town. Before the war, there were 2,000. Like many other young people in the town, their daughter Noa left at the age of 16, went to Tel Aviv, and then to university in Belgrade. Trees, tranquility and slow-paced life don't generate job opportunities.

Jokić grew up in a small apartment on the top floor of a four-story residential building (after signing a big contract, he bought a large ground-floor apartment for his family, 150 meters from his old home). He has two older brothers: the eldest, Strahinja, was good at basketball and played in the professional league in Serbia; the middle brother, Nemanja, played college basketball in the United States but squandered his career on partying, women and alcohol.

More than a decade separates Nikola from his two brothers. When he's alone with Strahinja, he undergoes a series of lessons. In one instance, he refuses to climb a tree. His older brother stands him against the tree with his back and throws knives around him. When Nikola joins the Serbian league, his brother comes to monitor his nutrition and training regime, even forcefully.

"But don't forget," says Fišer, "his brothers were born into war, into adversity. He was born into a different reality. That's why he's not as stubborn and macho as they are, and like his father in Branislav."

"His father and his brothers are nothing like Nikola. They are much tougher. Much more temperamental, much more inclined to engage in physical confrontations," recalls Lukić.

"They were very mean to him, but at the same time, they were very good to him. They taught him not to fear, not to be intimidated, to be tough. He was much more of a mama's boy. You can see it in his burek-and-Coke diet, but also in his sensitivity.

"Sometimes he would ask us a thousand questions, and all the teachers would go crazy from it. And then a game would come, and we would understand the purpose of those questions. That's how he builds a vision. He absorbs ideas. That's how he finds answers within situations. You see his behind-the-back pass and say, 'Wow, I see where that comes from,'" she says.

I tried to find Nikola's teammates, who have played with him in the past, but it turns out that almost all of them have left the city. Two young women sit in the square, looking at YouTube videos of Jokić, including the announcement of his selection as the Finals MVP. "Nikola is the new sexy man," one of them says. "No muscles, but with a sense of priorities focused on family, country and modesty."

Just don't tell Jokić that. It turns out that his continued pursuit of volleyball in high school was not solely driven by pure altruism. He saw a volleyball player from a nearby school and fell in love with her. Volleyball became the means to overcome his shyness.

"She was his only girlfriend, and he married her," says Forgić. "When she went to play college volleyball in Oklahoma, his heart broke. That's what pushed him to go play in Denver, not far from there. If she had played in Barcelona, he would be the best player in Europe today and leading Barcelona to championships."

'Money doesn't blind him, nor his loyalty'

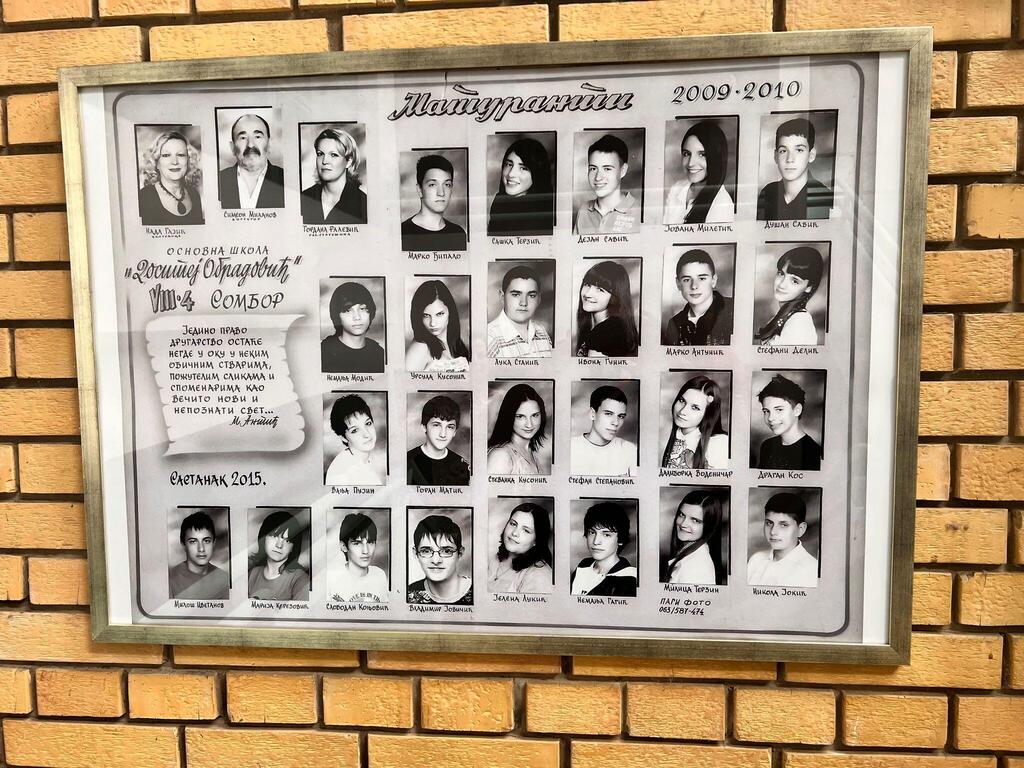

Vladimir Karanović has been teaching at Dositej Obradović School since 2008, and for the past six years as the principal. On the wall facing the street, someone painted in red: "Kosovo is Serbia."

On the adjacent wall, facing the open basketball court, there is a gigantic mural of Jokić wearing the white and navy blue Denver uniform. His right hand is close to his body, while his left hand, the weaker one, guides the ball. His mouth is perpetually open. Across his chest, it says "Joker" in Denver’s vibrant blue and yellow colors. Above his left shoulder, it reads, "Don't be afraid to fail big." Jokić studied here from first through eighth grade.

"He was always polite, a good student, funny, looking out for the weak, even at his own expense," Karanović recalls. "He was very calm, sociable, but not with girls. Girls at this age like boys with a tendency to do naughty things. He was a good guy with a good, protected childhood, but we did guard him sometimes from an elbow to the face."

There are two legends about Jokić in Sombor. Once, he received a call from Nike's advertising agency, telling him he needed to come to America to shoot a commercial. Jokić told them they had two days to come to Sombor, and then they had an hour to shoot. He showed up for the photoshoot wearing flip-flops.

When he received his second MVP award, he was already in Sombor after an early playoff exit. Denver's management and the league came to Sombor to present him with the award at his family’s horse stable. Jokić appeared on a horse-drawn carriage, barefoot.

"If you want to respect us, get to know us, you come to us – not the other way around," says Karanović. "We never knew where he would end up, certainly not like now, but the empathy, humanity, lack of ego, the instinct to share, to be an equal part of the team – all of that has been there since he was six years old."

You all paint a picture here of the best basketball player in the world, and a person a million times better than that. Almost perfect.

"Why 'almost'? People complain that he doesn't talk much, but he keeps to himself - and speaks through actions. When a person speaks less, what they do say becomes important. He's incredibly funny, but mainly knows how to laugh at himself. You have to understand: he earns $51 million a year. Our municipal budget is $20 million. But when he comes here, he's one of us. Money doesn't blind him, nor his loyalty, nor the responsibility he has toward his family. He's godlike. Someone touched him when he went out into the world."

'He was born to play basketball'

Siniša Savović, 50, was Jokić’s first basketball coach from the age of 7 until 11. He showed me Jokić’s player card, the only one that was accidentally stamped twice.

"I first met him in 2002. He was 7 years old," he recalls. "A big kid who clearly had a fondness for unhealthy food. The difference between him and the others was that he approached the game like a child approaches a toy. He loves to play, he enjoys it. That's his comfort zone. He didn't care about his position or what he would do, as long as they were winning.

"I taught him all the basics. Dribbling with a tennis ball, dribbling with just his left hand, using his body, playing in every position. But he was born to play basketball. I invested everything in him because within a few minutes, I realized how much potential he had, even though I had no idea he had so much potential," according to Savović.

"I had to teach him to keep his composure, to let the game come to him, and now you can see it. He has fulfilled his potential. Everything clicked in the right place and at the right time. He joined the right team, and he took his time to improve and get to where he is today, both personally and as part of the team. He didn't rush anything. He put his destiny in the hands of the team. It's amazing for such talent," he adds.

"Nikola is like an artist reaching his peak. I don't think there's much room for improvement. He will play for another three or four years. You just have to see him because there's no way to understand what goes on in his mind, what he sees. He's the first since Magic Johnson who makes you enjoy basketball. Jordan was a machine.

"When I’d tell them to sprint back and forth, the others would catch up to him on the way back while he hasn’t even reached the finish point. He quickly realized that the most important thing for his career would be to train his mind, but all the things we see now – the humility, the passing, allowing people to express themselves, allowing the coach to coach – were already there at the age of 7," Savović says.

"I think he was drafted very low (41st overall in 2014) also because of the failure of Darko Miličić (his fellow countryman who was picked second in the 2003 draft and went on to have a disastrous career until his retirement at a young age). That was another obstacle he had to overcome. He also never got injured because he's completely in tune with his body. Nothing affects him. He doesn't care about what people think or say about him. He's the Einstein of basketball."

"Nikola has always been a different kind of child," adds Forgić. "He would often visit the farm as a teenager. I used to go to the nearby veterinary clinic, and he would always be sitting there barefoot and shirtless. I would ask him what he was doing there, and he would tell me that these animals possess intelligence, beauty and elegance. It was his little piece of heaven."

'My son did something that is every child's dream'

Nowadays, his father Branislav, an agricultural engineer, has a horse stable named after the first horse Jokić bought – Dream Catcher. I met with him at his office on the farm, not far from the local racetrack. The office is adorned with a multitude of impressive awards and trophies. None of them belong to his son – they were all won by the horses. The sole mention of his champion son is a small black-and-white photograph of young Jokić, being pulled in a carriage behind a galloping horse.

"I didn't go to the NBA Finals because someone had to take care of all the horses here," he says. "At the start of the fifth game in the finals, I was with my wife, but after that, I was alone. I was too nervous. When it ended, there wasn't a big celebration because it was early in the morning, so we had a little toast. But there are a lot of mixed emotions. My son did something that is every child's dream. It saddens me greatly that I wasn't there with him at that moment," his father says.

The interpreter interjects and tells me, "He won't tell you this ever, but what he's actually saying is that he cried."

Branislav continues: "What was amazing was how he behaved right after winning the championship (referring to his son going and high fiving all the Miami players). Those qualities were always in him. Understanding the defeated, being empathetic, humble. He was always a good kid. When his daughter was born, it became even more apparent. His priorities are family, horses and basketball.

"When he was 1 year old, I took him to his brothers' games. He would sit on my knees, not speaking, not crying, not shouting, just observing the game. Basketball was his life, and then the horses came along. He wanted more horses, but I told him to excel in basketball first, and then he could buy as many horses as he wanted," he says.

"His older brother Strahinja worked hard to become a basketball player, and the middle one had a lot of talent. Nikola learned from both of them. They shaped him. We knew he would be good, but not this good. He was the best, the greatest and the chunkiest. He did what he wanted. He plays the same basketball he played as a child. The same thing. Even in life, the same thing. A parent couldn't ask for more from their son.

"I'll tell you a story about Nikola, and we'll finish here because that's the whole story. When he arrived in Denver, he had a Serbian coach for player development, Ognjen Stojaković. Nikola didn't like him because he made him work extremely hard. When Nikola's daughter was born, he named her Ognjena. He understood what that coach did for him," his father says.

Saturday night, Jokić returned home. The work has been completed. There are horse races to attend and batteries to recharge. There is another summit to conquer.