Unlike many creators and intellectuals, especially given his iconic status, Ian McEwan doesn't need convincing to talk about Israel and especially its politics. In fact, our formal conversation had barely begun (of course, the initial small talk was dedicated to judicial overhaul and protests against it) and he's already finding a way to compare the disillusionment of Roland, the protagonist of his latest and beautiful book Lessons, to the hope that Israel will one day realize that the occupation is weakening and draining it.

Read more:

“I always cross my fingers that Israel just get weary with this thing with Palestine,” he says in a Zoom call from his home in England,” just say let them have a fucking country. Let’s just live together.

Before one can even ask him who exactly is waiting on the other side—the weak leadership of Mahmoud Abbas or the fanatical dictatorship of Hamas—McEwan's memory sails back to his visit to Israel in 2011.

He came to accept the Jerusalem Prize from the Jerusalem International Book Forum, which, of course, drew sharp criticism and a campaign from the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement, as has been the case for years before any visit by a British cultural figure.

Unlike others, McEwan did not waver or fold. He arrived to accept the award, announced that he would donate it to the Combatants for Peace movement, and in the presence of then-President Shimon Peres and Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat, delivered a speech criticizing the occupation and the settlements, which was met with some jeers.

Now he recalls what happened afterward. “What was the mayor’s name?”

Barkat. And no, he’s economy minister now.

“He came to me and he wasn’t pleased with my speech. Because I said there that the settlements pour concrete over an idea that it will be very hard to find a way back from. It will be much harder to break the concrete than the idea itself. But there was also a great moment after the speech. Shimon Peres came to me, hugged me and said, ‘I wish I were delivering this speech.’ I told him, ‘Yeah, I also hoped that you do it too’.”

And suppose you'd receive an invitation to come to Israel today. would you agree?

“Just to be clear, the answer is yes. But it depends on who will issue it. Would I have visited Russia? I think that for my own security, I better not. But in theory, there are always good people and you want to be in touch with them. The problem is most of them fled or in jail. Only a few people left in Russia to talk to.

I received an award in China from a university and I met good people there. I hoped that if China became a global power, it would also start using soft power, but things have changed for the worse. I talked at a press conference there about Chinese literature and I mentioned Taiwan and I saw how all the pens in the room dropped. Nobody was going to write what I said."

"Like the book," he summarizes the issue of legitimacy for problematic regimes and extremist governments, "Roland expects that one meeting will set him free from a 40-year-old trauma, but there’s no complete solution. You want to communicate with the best, the ones who dedicate everything to open society. And then this door starts to get shut. In Turkey too. It’s a strange thing, populism. You see Brexit and what came out of it – nothing from the good they promised – and you think: I’m starting to hate democracy."

Married to the project

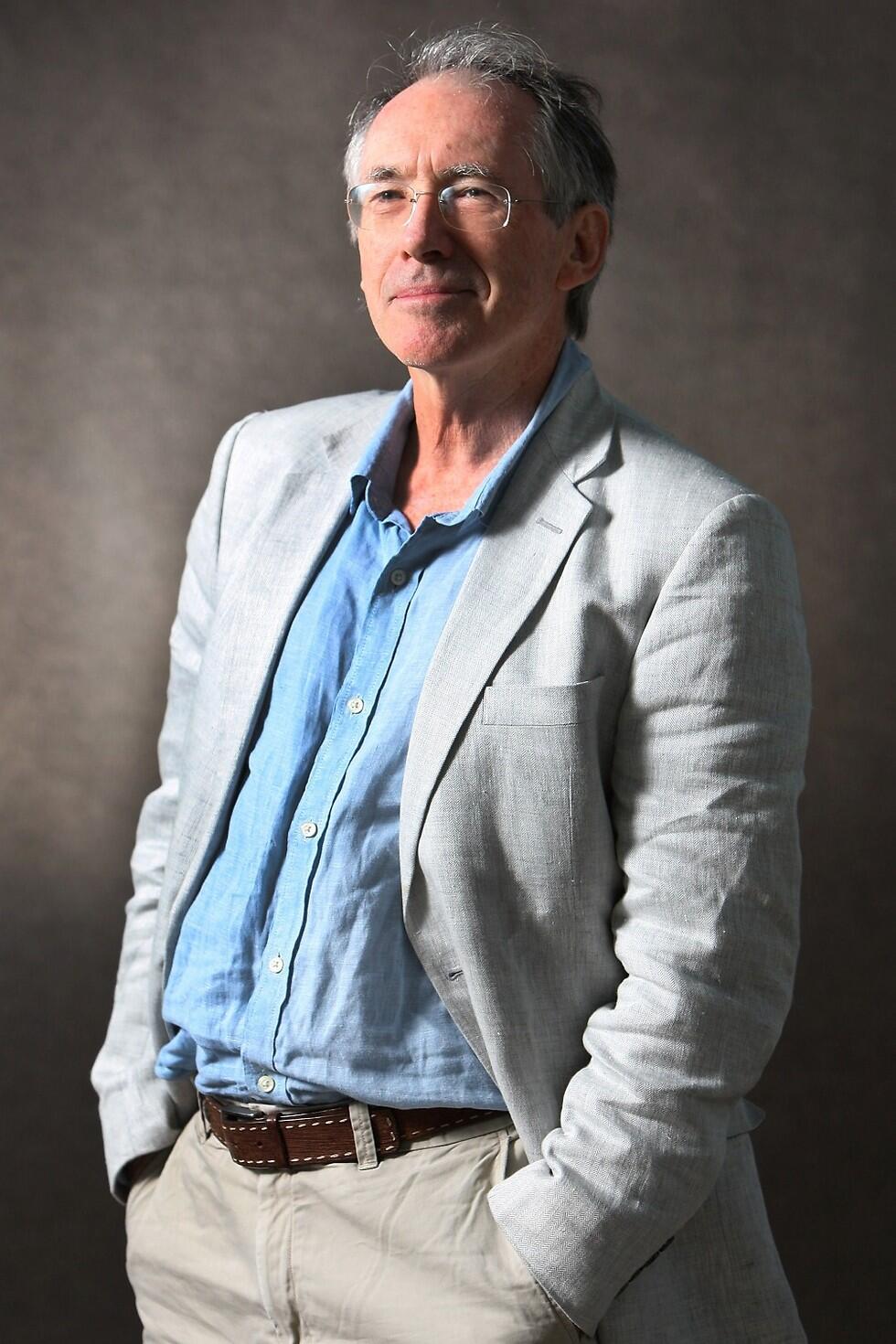

About a month after celebrating his 75th birthday with his family and friends, McEwan is not only sharp and vibrant as if we're in the mid-70s and he's just emerging as the dark prince of modern fiction.

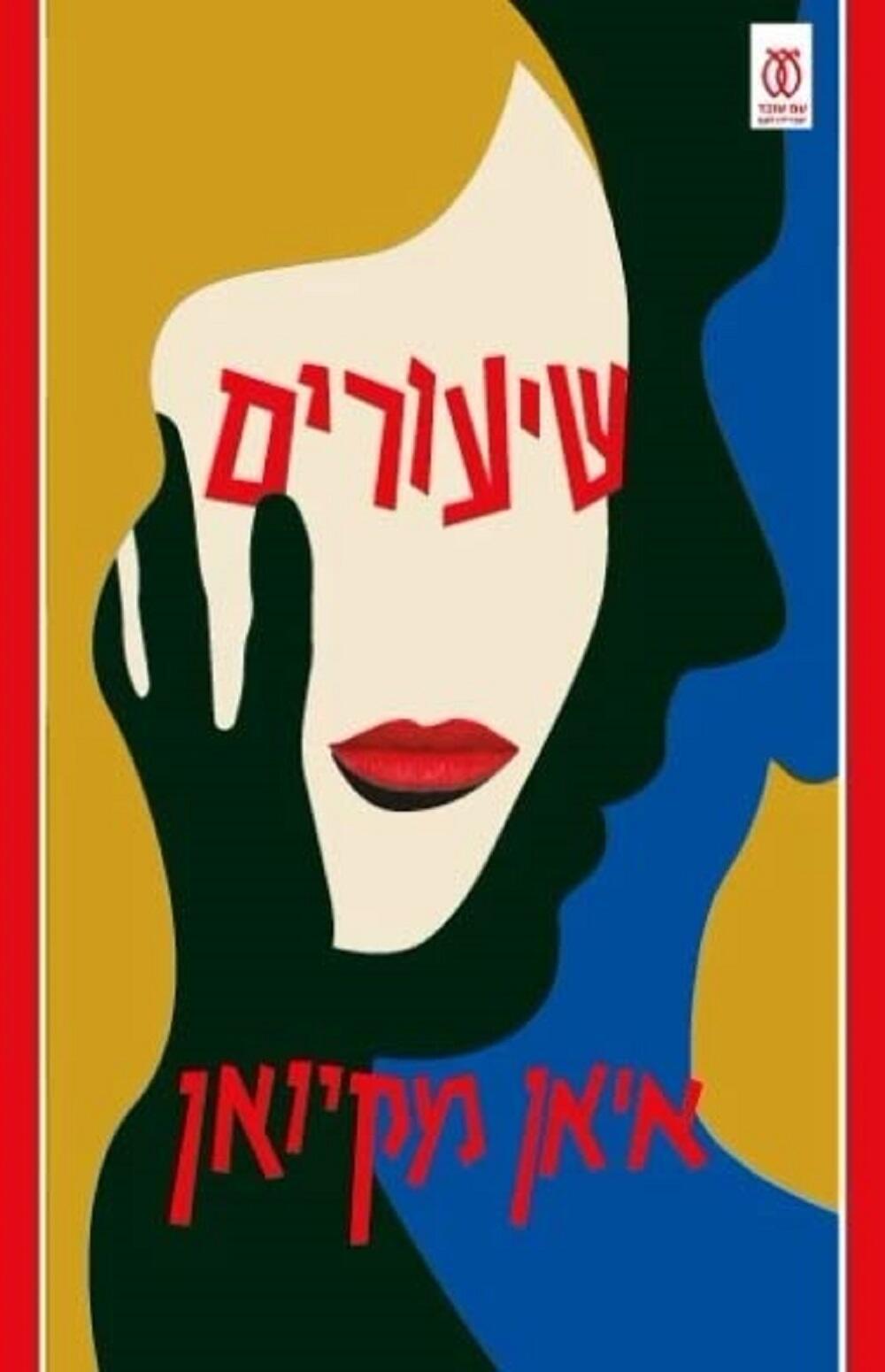

Lessons, released about a year ago and soon to be published in Hebrew by Am Oved (translated from English by Amir Zukerman), finds this exceptional writer in a state of unusual openness and willingness to tackle various chapters of his real life, from complicated relationships with his parents to the unsettling discovery 20 years ago that he has an older brother who was given up for adoption.

With the nuanced skill typical of this writer, McEwan has projected himself onto the book's protagonist, Roland, based on the assumption that he could easily have been Ian McEwan. In line with the current trend in cinema, Roland is Ian McEwan's multiverse version.

I think the first question is why now. Technically, you could have written this book even a decade ago.

"I think that a big part of the answer is that I’m in my mid-seventies. It’s a time to reflect on only on global events that shaped our lives and penetrated them, but also to deal with personal life through them.

I could have written a memoir, I’ve been asked so many times to do that in the last 30 years, and every time I said yes and it didn’t happen, because I wanted the freedom of the novel. That’s why I gave the hero some autobiographical details and other notes, like from the fall of the Berlin wall, which were taken from my notebooks. But I also wrote from within his skin. So why now? I guess it’s the novel I was always meant to write."

Indeed, Roland begins the life journey that McEwan has created for him with a chilling key scene that takes place during a piano lesson at a boarding school. From there, he continues to traverse the key points of the 20th century, from the post-World War II era to the early signs of the unraveling of the global order in the 21st century.

Reading Lessons is a constant intersection between unforgettable historic moments and the reality of a man whom only a few will remember. At the forefront is his only son, Laurence, whom he raised alone after both were abandoned by his wife, who became a celebrated writer and wanted no further contact with them.

"Most problems in life are unsolvable. Most traumas in life are not solved. You either forget them or they become a part of who you are and what you are, part of the cargo you must carry"

Hovering above it all is that same piano lesson, which led to a tragedy involving both first love and the unbearable exploitation of a teacher by her student—a gap Roland will never stop pondering and trying to resolve.

"I’m always asked, what are the Lessons that the book talks about. At the beginning, I answered that the lesson is that there’s no lesson. Then I thought, 'it’s an unsatisfying answer.' So I’ve worked on an answer and I came to this conclusion: most problems in life are unsolvable. Most traumas in life are not solved. You either forget them or they become a part of who you are and what you are, part of the cargo you must carry.

Many novels and films have misled us to think that problems are solved between people when, for example, to fall in love or kiss and make up or hear the forgiveness they were looking for. But if you lose a close friend or a lover, it’s part of who you are and will go with you to your life’s journey. There’s no closure, that horrible American word."

Roland's formative trauma didn't happen to you, and I thought it was a clever way to distract the reader from the details that are actually taken from your biography: for example, the sad relationship between your parents.

"Well, I did have piano lessons, but my teacher was very distant. I didn’t know anything about her besides her perfume scent. It became my Rosebud. But I could imagine how what happened to Roland could have happened to me when I was 14. I can imagine how it is to be confused your whole life because of the ambiguity of an experience that had love but was actually abuse."

The book mentions the publication of an autobiographical novel that arouses controversy because of its exposure and the harm to the people mentioned in it. Since the book does include details that are quite identifiable with you, is this something you have thought about?

"That’s an easy question to answer: the moment I sit on this chair, in front of this desk, in this very lovely barn that was made into a home, like any other of the homes I lived at, I don’t think about what the readers or scholars and the rest will think. It’s a very nice place in its emptiness.

Sometimes, even after 20,000 words, you don’t know where you’re going. But the moment you do – that’s it, you’re married to the project. And like marriage, you have doubts and sometimes you stick to something just so you won’t have to admit that you’ve wasted time. But the moment the doubts are solved, there’s absolute freedom."

For example, McEwan embeds in Roland's history several developments he himself is intimately familiar with. Roland, for instance, spends his childhood under the shadow of a father who was an alcoholic officer and who occasionally hit his mother—just like McEwan, who only found out about this when he was in university. From his bitter divorce from his first wife and the mother of his children, Penny Allen, who took one of their kids to France, he leaves Roland with the experience of single parenthood.

Later, Roland discovers that his parents met while his mother was still married to her previous husband, and together they had a child who was given up for adoption. This was also the case in reality, when McEwan's mother posted an inconceivable ad in a local newspaper: "Home needed for one-month-old baby. Complete relinquishment."

In 2002, McEwan discovered the existence of David Sharp, his long-lost brother, after their father had passed away and their mother had succumbed to advanced Alzheimer's and died a year later.

"I had to deal with the experience of meeting my new brother. I always knew I would have to write about it, and also about my mom and dad who gave a baby in a train station. I just knew it will come in the form of a novel," he says.

You know better than me that the book no longer belongs to the author once it is out. I'm curious to know how your kids read it.

"My two boys are 38 and 40, and many of the details in the novel are quite familiar to them. In many aspects, I raised them alone in their early teenage years until they went to uni, so we spent plenty of time together. They didn’t know much about their grandfather, but for them, he was a positive character, so there are some voids that’s been closed since. I don’t think the details in the novel are somewhat of a revelation to them."

By the way, Roland reads quite a few writers of your time. For example, your friend Salman Rushdie. I wonder if he read Ian McEwan.

He laughs, "Oh, he definitely likes his books, sure. No doubt. On Sweet Tooth, there was a character of a novelist that was sort of my reflection, and also in other stories. Here I had to avoid."

It's an interesting intellectual exercise: the hero is someone you could be, but you yourself don't exist.

“It’s wonderful to contemplate the accidental nature of life, that if you’re father had made love with your mother five seconds earlier or afterward you didn’t exist. I was sent to boarding school based on the sergeant’s recommendation who told something to my father, who was a captain.

My father didn’t know anything about boarding schools, he left school just like my mother. And I had the most wonderful experience there, that saved me from a miserable and intense family situation. And everything thanks to a word of someone I don’t know his nature. I thank him anyway.”

Every writer is a kind of God of the characters, but when you decide that Roland will be you minus the writing, it's even more powerful.

“You’re asking me if I see myself as God when writing a book? Eventually yes. But I wrote him from his inside. All the time. All I had to do is to consult my feelings. When I was 18 or 19, I knew that I don’t want ‘work’, so if I hadn’t discovered writing, I would have lived Roland’s life. I would have lived on the margins.”

Not troubled by AI

Lessons is not only McEwan's most personal book but also his longest, compared to his previous 17 books, which include masterpieces such as Atonement, Amsterdam (for which he won the Man Booker Prize), Enduring Love, Black Dogs, On Chesil Beach and more.

"The great revolutions I saw in my life were the gay revolution, the feminist revolution and the race revolution. The patronizing way that men talked freely was just sickening. The gay revolution is also not only about legislation. In a survey they made recently they discovered that 88% of the British public support gay marriage. In the past, it was maybe 2%. That’s an extraordinary change"

The ample pages allow readers to understand how McEwan himself views what unfolded before his eyes, whether it is the fall of communism or the way the literary canon is changing in light of identity politics.

Much like in his public appearances, McEwan takes care in the book to walk a fine line between the curiosity to hear silenced voices and the fear of cultural appropriation toward the population group McEwan himself belongs to: white, privileged males.

"The great revolutions I saw in my life were the gay revolution, the feminist revolution and the race revolution. If we would enter a time machine and go back to, let’s say, 1965, the patronizing way that men talked freely was just sickening," he says.

"The gay revolution too, for example, took years, and it’s not only about legislation. In a survey they made recently they discovered that 88% of the British public support gay marriage. In the past, it was maybe 2%. That’s an extraordinary change, and it doesn’t end until we accept more forms of sexual preferences."

"And at the same time," he adds, "I find it troubling that people feel they have to be in a ‘safe space’ or that they feel threatened because someone comes to a university to talk, although we have the privilege of living in a country that has freedom of speech. Unfortunately, it comes mostly from the left side. Although in small parts of it, but we shoot ourselves in the leg.

I suppose you mean like the calls to cancel J. K. Rowling for her comments against trans women.

"Yeah, I signed a letter of support in her, sure. But it’s important to say that this discourse has made a revolution and made us deal better our colonial past."

"You know," he continues, "there’s a petition calling for banning the works of David Hume because he had all kinds of opinions. You can’t censor the past. That’s the part of the issue and I'm strongly against it, it’s exactly what the American right brought, where they want to prevent kids from getting access to one book or another. So I have mixed responses but the general sentiment is that I have been lucky to live in times of change."

But let's give David Hume a moment or even Richard Wagner. They are gone. What do we do today with brilliant artists who have abhorrent views, in a society that is fighting for democracy against dark and manipulative forces like populism?

"I think it’s one of these unsolvable problems: There are brilliant people with evil opinions and there’s nothing you can do about it. Dostoievski was a great antisemite, and you need to live with the contradictions. That’s one of the problems with this movement, who wants a single answer although you have at least two: brilliant artist, despicable person. You need to live with this complexity. You’re told not to go and watch some actors because something horrible they’ve done, or not watching films by Woodie Allen. Fine, don’t watch, but don’t stop me from doing it. I want to watch Woodie Allen films. Get out of the way."

Meanwhile, there's at least one revolution that McEwan seems less concerned about: artificial intelligence. And it's not for a lack of knowledge. In 2019, he published Machines Like Me, a science fiction and alternative history novel that deals with the relationship between a man and his android.

Three years later, as the world is shaken by both the opportunities and threats of artificial intelligence, McEwan knows that at least in his lifetime, there's no chatbot on the horizon capable of replacing him.

"I haven’t yet seen anything that is particularly disturbing. Maybe in the world of visual arts and even music. But in literature, it can take more time, I don’t know how much. Literature means to be embodied and understand the great complexities of social relationships. Writing a novel is to live within possibilities, describing how it is to be someone else. From what I’ve read so far, we’re more in the direction of AI as a faster scanning tool than as a substitute for novelists."

Before the interview, I wanted to ask ChatGPT to write me a paragraph in the style of Ian McEwan...

"My son asked the same."

And what was the result?

"Pathetic."

On the other hand, McEwan maintains a very warm relationship with the worlds of television and cinema, and not only because his books are considered hot and popular goods in the industry. "I am totally addicted to Succession. Totally addicted to La Bureau I. loved The White Lotus," he says.

Is this in your opinion quality or guilty pleasure?

"I don’t believe in guilty when it comes to pleasure. Recently I watched some episodes of Breaking Bad to cheer up."

Breaking Bad is cheerful in your view?

"Yeah, yeah. Because its premise is just genius: a chemistry teacher who is a natural as a crystal math creator, and he finds the worst in his classroom, and they become business partners? Brilliant."

So I understand you won't object to Lessons becoming a TV series.

"I want a 100-episode TV series. I really think that if I were 25 or 30 today, I'd be in a TV series’ writer’s room. That’s what I would have done. It’s a wonderful form of art, with the depth of a Victorian novel. In my opinion, the closest are Anthony Trollope novels, that I’m obsessed with at the moment. Take also the TV series based on Alena Ferrante novels. The castings there are just incredible."

So who will play Roland in the 100-episode series?

"I think we’re going to need three actors, one for each period. I have many good friends in theater, and I always ask them who to cast for something I am working on. They gave me the name of a wonderful young actress. And then the casting director and the director say no. four years later she is the most famous person on earth. It’s always like that."

So who will play Roland?

"It should be someone who got banned. Someone we are told it’s forbidden to see."

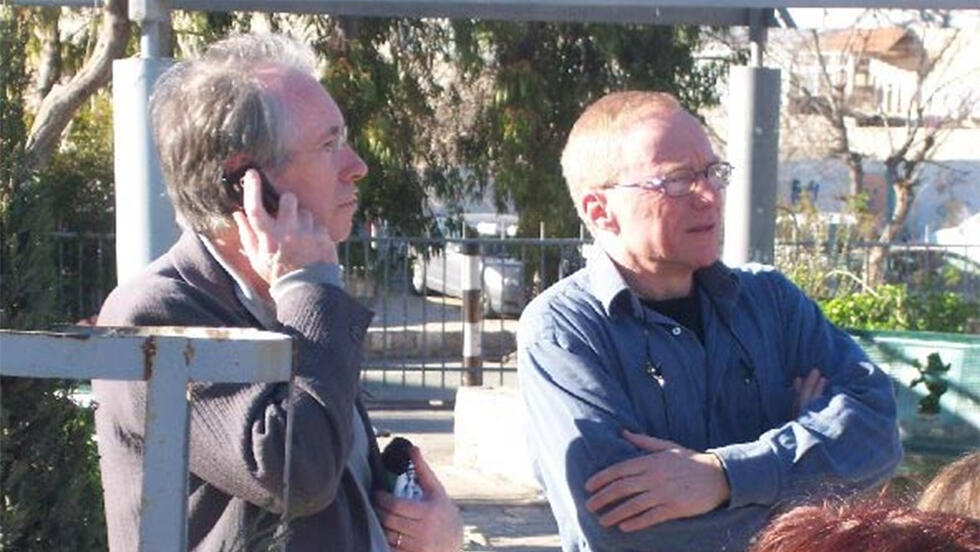

Before concluding, I ask McEwan when he last spoke with his good friend David Grossman. He says that the two recently spent quality time together on a trip to Porto Alegre, Brazil.

David Grossman and Ian McEwan in Porto Alegre — now that's a story I would read.

"He was in fantastic form, and the time we spent together was very important to me, so I hope to see him again one of these days. When someone builds a David Grossman machine, I say that everybody will be happy. That’s how everybody will have the privilege of being close to him, like the privilege I had in Porto-Alegre."