Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

These images have no chance of being erased from memory, especially since it was all broadcast on live TV. A drama unfolded before the eyes of the spectators at the event and on-screen — the Artistic Swimming Solo Free finals at the World Championships in Budapest, in late June 2022.

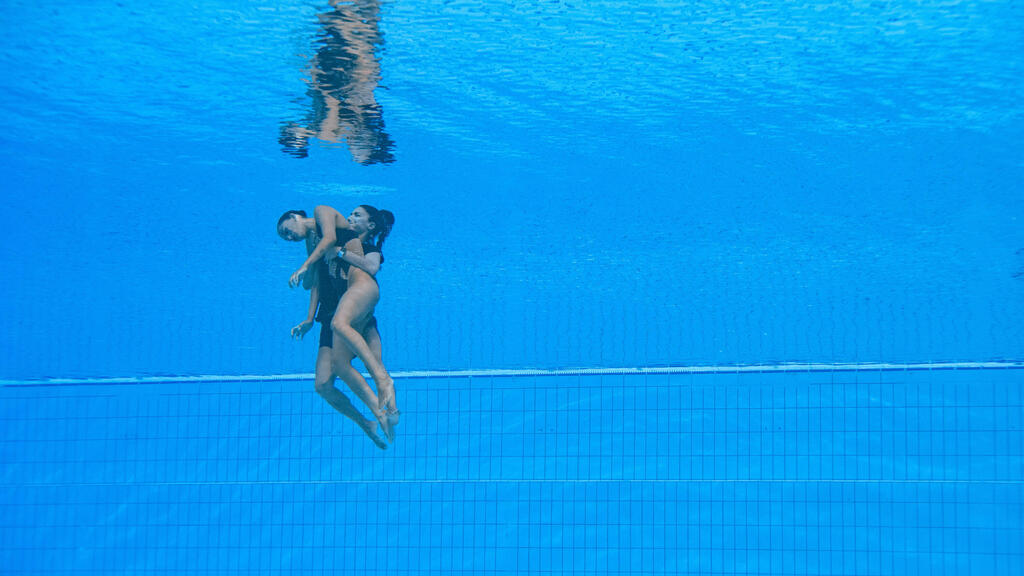

American synchronized swimmer Anita Alvarez lost consciousness in the water and sank to the bottom of the pool. "The lifeguards did nothing," recalled her coach, Andrea Fuentes. "I ran and swam to her as if I were in the world championships. I saw she wasn't breathing, used the pool floor to push both of us above the water, and started slapping her. Then I dug my pinky nail deep into one of her bones, and the adrenaline brought her back to consciousness."

A year earlier, at a competition in Barcelona, Alvarez also lost consciousness at the end of her routine. Back then too, Fuentes, a four-time gold medalist in the sport, saved her.

Many athletes lose consciousness due to overexertion. They search for their limits and find them. In a pool, however, this is doubly dangerous, especially considering that artistic swimmers sometimes hold their breath for nearly a minute underwater.

At the World Championships in Fukuoka, Japan in July 2023, Alvarez and her teammates won a silver medal in the acrobatic routine and a bronze in the technical routine — the best American achievement in 16 years. "It was excellent preparation for the Paris Olympics," she said after the medal ceremony.

"I feel great to be back. It’s been a long journey, even though I’m currently only allowed to swim in the team event, not solo," Alvarez added. "I'm almost there physically, except for some additional medical tests I need to undergo, but I still have a long way to go to reconnect with my sport mentally and emotionally."

4 View gallery

Anita Alvarez lifted out of the water after losing consciousness

(Photo: Dean Mouhtaropoulos/Getty Images)

After losing consciousness and sinking into the water in Budapest, Alvarez took a few months off from training. Doctors discovered she had an iron deficiency that affected the production of hemoglobin, the main component of red blood cells. This caused fatigue, an almost insurmountable factor in a sport demanding such endurance as artistic swimming, which requires quick breaths and holding them for extended periods.

Since then, she has been working regularly with a psychologist to regulate her breathing. She doesn't remember anything about the ordeal, from the critical moments when Fuentes jumped into the water and possibly saved her life.

Manuel Halbisch

German diver Manuel Halbisch climbed onto the giant cliff at the 2023 World Aquatics Championships in Japan. In this event, competitors jump from heights of 20 and 27 meters. It's a steel monster that offers views of the local baseball stadium, the sea, and the city.

Above him were only blue skies and a remotely controlled TV camera. Below him, in the pool, five divers were waiting just in case. Halbisch tried to clear his mind and focus, but his thoughts drifted back in time, four years back.

There are no elevators here. The feet burn from the climb in 35°C heat, a sensation that didn’t subside even after each of the four jumps by every diver. Like many of the divers, Halbisch wore a heart rate monitor. Typically, the heart rate at these heights ranges between 120 and 150. It would be higher if you're about to attempt a new trick.

The body mixes a blend of fear at the edge of the drop and preparation for pain at the moment of impact. Divers hit the water at a speed of 85 km/h from such a height, generating a 10-g force.

During that jump, Halbisch realized something was going wrong. "I was 10-12 meters above the water when I realized I was going to land badly," he recalled. "Then your whole body stretches and tenses, enters a state of shock, just waiting for the hit, I couldn't maneuver and do another flip into the water."

Halbisch landed on his back instead of his feet. "I was hospitalized for only nine days, mainly because my injuries weren't severe," he said. The medical report paints a slightly different picture: pneumothorax (accumulation of air preventing the lungs from expanding and contracting, taking in and releasing air) and small punctures located in his lungs.

He continued to work full-time as a police officer at Stuttgart Airport’s helicopter department. And he kept jumping off 20-something meter cliffs, as a hobby. But after missing the World Aquatics Championships in South Korea, he became the first German to qualify for the contest in Fukuoka. Halbisch hoped to finish among the top 20 and was ranked 18th.

He has no funding and no sponsors. He received $500 for his participation in Japan. In one day, he jumped from a 27-meter platform five times. In another training session, he jumped from 20 meters 13 times within an hour and a half. He usually has to travel hours to reach facilities with platforms at these heights. "And even when I’m there, at that height, I never forget the accident I went through."

Halbisch and Alvarez are two more stories. Relatively unknown athletes if not for the severe and unfortunate accidents they endured. But amid all the corruption, hosting competitions in countries without human rights, disloyalty, greed, and whatnot, it’s important to tell their stories. Of pure love for the sport. Of those who continue to swim, run, jump, and leap, and not give up, with complete dedication.