Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

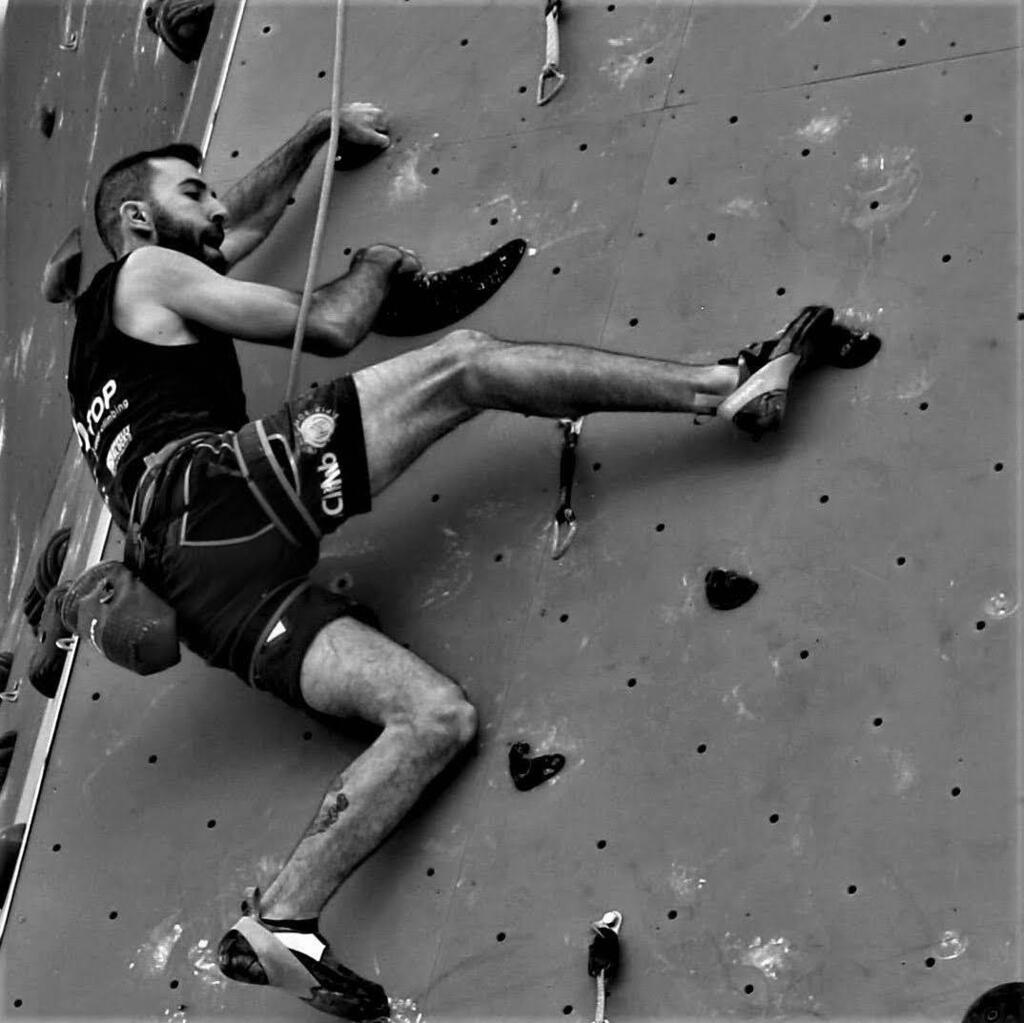

Israeli Paralympic climber Mor Sapir, 33, has been living without fingers for nearly a decade after losing them in the 2014 Annapurna snowstorm disaster in Nepal, which claimed the lives of 43 trekkers, including four Israelis. Despite his disability, Sapir chose not to sink into despair, and climbing has become part of his journey toward independence.

This week, Sapir achieved a major milestone by winning a silver medal at the European Championship held in Switzerland. To understand the extent of his determination, it’s worth noting he participated in the event — the largest competition he's attended this year — after completing 200 days of reserve duty in the IDF amid the war in Gaza. On Friday, he returned for his third round of reserve duty.

Finding solutions, regaining independence

Sapir began seriously engaging in climbing seven years ago, initially using the sport as a rehabilitative activity. Sapir was originally an officer in the IDF’s Combat Engineering Corps and he worked in demining for civilian companies even after his discharge.

"I felt like my hands were made of steel, that nothing could happen to them," he recalled. "Before my trip to Nepal, I signed up for a basketball coaching course. I played for Maccabi Rehovot Basketball Club as a teenager. I really love basketball."

What do you remember from the days after the disaster in Nepal?

"I suddenly encountered many simple tasks that didn't require strength but rather a limb to complete the movement. There was a disconnect between my hands and my brain. I felt like I was trying to open a car door and got stuck. Everything was very awkward, almost impossibly so in my mind."

Like a baby learning everything anew?

"Exactly. I was frustrated and disappointed. Physiotherapy didn’t really help either — they just offered 'solutions' like extending a zipper with a safety pin so I could pull it. It’s like a painkiller for a headache; it doesn't solve the problem, only provides temporary relief. During that time, I realized I had to push myself. People can support you, but if I wanted to regain my independence, it was up to me alone,” he explained.

Did you meet others who had their fingers amputated during rehabilitation?

"No. There aren't many people like me — not just in Israel, but in the world. Other competitors might have only one hand like mine. This is about breaking new ground. When I joined the Combat Engineering Corps, they told me I was meant to break new ground, part of the induction hype you saw the recruitment base.”

“Suddenly, I realized this was going to happen to me, born out of pain. If I keep crying and complaining, it'll only weaken me more. That’s not the confidence I want — to go to a pub, ask for a beer, and be able to hold the glass,” he added.

How do you manage that, especially in the age of smartphones and touch screens?

"It was very hard. Back then, we had SMS; I'd send messages like 'come,' 'down,' 'when' — just one word to minimize the effort. At first, my hands were bandaged, and I would type with my nose, elbow, or wrist."

What about activities like driving, drinking and eating?

"I did everything with my hands. I’d find another way. There are cups and tools that are more suitable for it. The difficulty for people is to imagine it. It took me a few years before I called myself a climber and a few more before I called myself an athlete. I became independent after two years and sometimes I still ask for help. For example, with untangling knots in wired headphones, which I still use."

The dream: Los Angeles 2028

You might ask — why isn't Sapir part of the Israeli delegation to the Paralympic Games that opened in Paris on Friday? While climbing has already entered the Olympic Games, it will debut at the Paralympic Games only in 2028. "It takes time for things to be included and accepted; it's a relatively small sport worldwide," Sapir explained.

"I was injured right after Operation Protective Edge, so I was connected to a group of disabled IDF veterans who did climbing," he recounted how he began his journey. "My hands were so sensitive I was afraid to shake hands with people. No one explained how much climbing relies on fingers and not hands alone. I was the worst on the climbing wall. Four-year-old kids and even a grandpa climbed better than me."

Did you ever think about giving up?

"No, because I had to regain my independence. Being dependent on others isn't living. There are grips that I say aren't for me, it’s like playing bowling. I wanted to break new ground for myself so I could look in the mirror and see a strong guy.”

“Every time I managed to grab an object while climbing, I grabbed another hold on the path of life. I fell in love with the sport. My dream is to compete at the Los Angeles 2028 Games and be on the biggest stage possible,” he said.

And you're serving in the reserves alongside your sport.

"On paper, I'm not even a volunteer; my military ability profile is still high. I wasn't active in the system until the war started. At first, I was the battalion's training officer, coordinating courses, lessons and equipment. Preparing the soldiers as much as possible. Then I was in the command center, watching over the battalion from above.”

“We were also on the northern border. In between duties, I flew to competitions, my reserve duty was suspended and now it’s back. Reserve duty and competitions are my mission. I don't travel only for leisure; I'm an ambassador. It’s important for me to tell climbers around the world that the real picture is different from what they see on the news — we're not child murderers,” he added.

How does it feel to complete your reserve duty, fly to the European Championship and win a silver medal?

"That we made it. We, not just me. My coach, Niv Cohen, and my wife, Naama, push and supports me so much. Now we're bringing together a professional team for next year. It's something I'm taking on myself, so the Israeli team will win more medals."