The brass sculpted faces are grotesque: with their misshapen hollow heads, mouths agape and nightmarish expressions. Some are covered in rusty barbed wire and have nails protruding from their skulls, while others feature a medley of metal objects one would most likely find abandoned in a junkyard.

The ghoulish heads stand on the rooftop of a building and peer down at the street below that marks the dividing line between east and west Jerusalem.

5 View gallery

Sculptor Reuven Hasak peers out of a piece of styrofoam in his Tel Aviv studio

(Photo: Tomer Shalom)

They are part of a recently unveiled exhibition at the Museum on the Seam – Israel’s only political museum – called “Gall and Wormwood.”

More importantly, the man behind the masks is none other than Reuven Hasak – an 81-year-old sculptor who once devoted himself to Israel’s security.

5 View gallery

A view of the Museum on Seam, where Reuven Hasak’s sculpted heads are currently on display

(Photo: Maya Margit)

In fact, Hasak served in the Shin Bet security service for 20 years, rising all the way up to the rank of deputy director until his career came crashing down in 1984 during what is now referred to as the Bus 300 affair.

Four Palestinian hijackers took several Israeli bus passengers hostage during the incident, which ultimately resulted in the deaths of all hijackers, as well as an Israeli female soldier who was killed in friendly fire during the rescue operation. Eight other Israelis were also injured.

The Bus 300 affair would shift the course of Israeli history, damage the reputation of the Shin Bet and forever change the way Israelis view the thorny issue of military censorship.

From his sunny garden studio in Tel Aviv – packed with an array of colorful paintings, posters, sculpting tools and miscellaneous items collected from the streets of the city – Reuven Hasak recounts the fateful event and its aftermath.

“A bus on its way to Gaza was hijacked by four [Palestinian] terrorists,” Hasak says. “Israeli soldiers stormed the bus; two of the hijackers were killed while another two were taken alive. The head of the Shin Bet at the time [Avraham Shalom] gave an order to kill in cold blood the two who were still alive - and they were killed.”

Although the IDF censor initially forbade coverage of the hijacking, which led to media outlets reporting that all four hijackers were killed during the rescue operation, press photographers who were present at the scene managed to snap images showing that two of the hijackers were, in fact, alive after they were escorted by security forces off the bus.

Now defunct Israeli newspaper Hadashot circumvented censorship orders and published the pictures in question, leading to a massive public scandal.

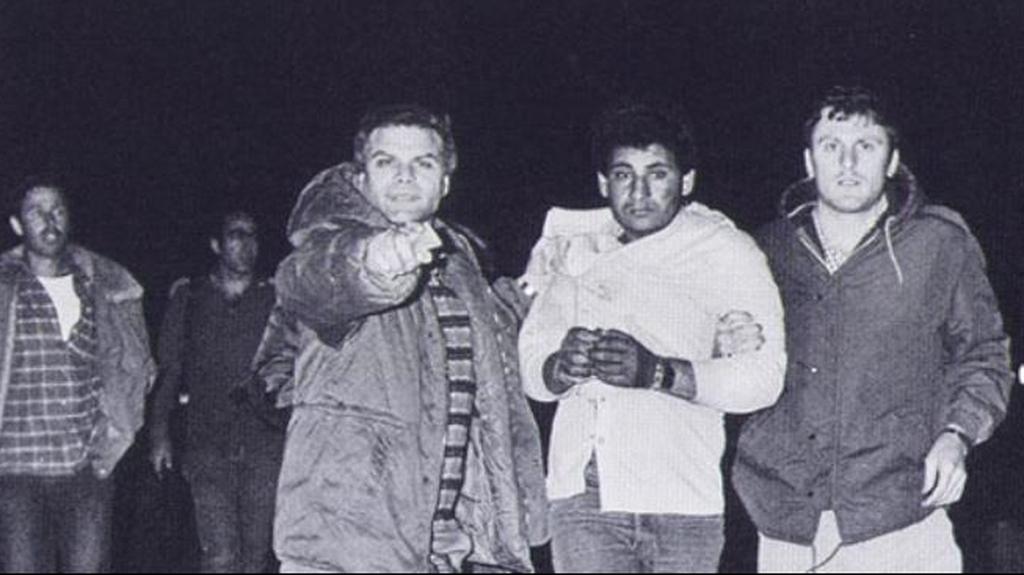

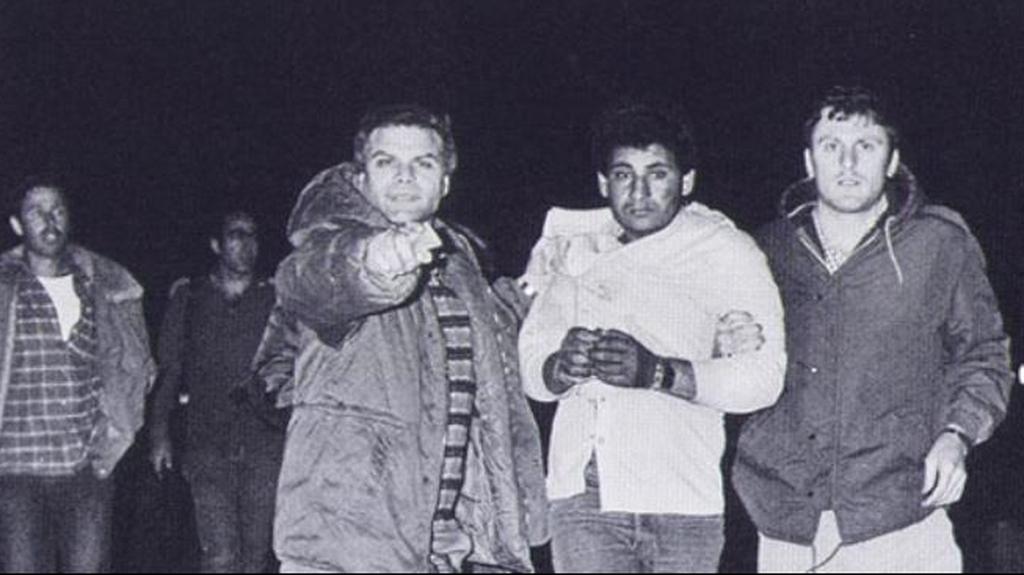

5 View gallery

israeli security forces with a captive Palestinian terrorist at the scene of the Bus 300 hijacking

(Photo: Alex Levac)

Hasak and fellow colleagues Rafi Malka and Peleg Radai meanwhile refused to take part in the cover-up and presented their evidence to Attorney-General Yitzhak Zamir, who launched a criminal probe into the matter and was also forced to resign after refusing to nix the investigation. As for Shalom, he left office shortly thereafter in 1986 and was offered a presidential pardon.

“Myself and two friends rebelled – all of us were senior members of the Shin Bet – I was number two in the organization,” Hasak explained. “We didn’t agree with the decision [to kill the two remaining hijackers] and we spoke to the head of the Shin Bet [Avraham Shalom], then-Prime Minister Shimon Peres and for the most part, our efforts didn’t help. We were fired and told to leave our posts.

“It was very traumatic and a very difficult thing [to do] – but I do not for one minute regret that we did what we did,” Hasak stressed. “With authority comes responsibility; you cannot separate one from the other. A leader has to make decisions as a leader and not as a politician. Shimon Peres made a decision as a politician, not as a leader.”

From security brass to sculpting brass

Today, Hasak has moved on from state security to expressing himself artistically by sculpting distorted and highly expressive faces out of brass. Hasak first began sculpting in the mid-1990s after meeting with Reuben Scharf, an Israeli sculptor living on the central Israeli kibbutz of Hulda. Scharf mentored Hasak and showed him a number of techniques.

For the first time, his provocative pieces are on display at the Museum on the Seam, part of a wider exhibition taking place there called “Democracy Now.”

5 View gallery

A view of some of the brass heads on display in Reuven Hasak’s exhibition at the Museum on the Seam in Jerusalem

(Photo: Maya Margit)

For Hasak, masks’ cruel and haunting appearance reflects his impression of Israel’s ongoing political stalemate, especially as the country heads into an unprecedented third round of elections after both leading parties – the Likud and Blue & White – failed to form a government.

“When I’m sculpting, I’m thinking about the situation in Israel and the fact that I’m not happy with what is happening in my country,” Hasak reflected. “I’m also thinking about our leaders, who I don’t think deserve to be leaders.

5 View gallery

Sculptor Reuven Hasak stands in front of several of his works in his Tel Aviv garden

(Photo: Tomer Shalom)

“I spent 20 years working for the security service and looking at the Palestinians through the scope of a rifle and I arrived at the conclusion that we cannot solve this problem with rifles,” he says.

“We [Israelis] have to talk to the Palestinians and listen to them, hear them and put ourselves in their shoes – and then try to find a common way forward.”

After their showing in Jerusalem, Hasak’s sculptures are slated to tour the United States in the spring, beginning in April at Expo New York, followed by exhibitions in San Diego and Miami.

Article written by Maya Margit. Reprinted with permission from The Media Line