Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

It was not a long intermission between seasons for The Israeli Opera: the last one ended just three months ago (in August), and the new season has already started, with the premiere performance last week. The lineup runs the gamut of both familiar and less familiar works, by the usual composers – Verdi, Puccini, Mozart and Handel – as well as rarely performed operas, and even a new Israeli work to conclude the season next summer.

The bold debut of the 2022-23 season was definitely in the category of operas not seen in Tel Aviv in recent memory: The Tales of Hoffmann, by 19th-century French composer Jacques Offenbach – who was actually born a German Jew.

This fact about the musically gifted convert to Catholicism is important in the context of the libretto of this last opera that he wrote, since there are several references to an unsympathetically portrayed banker pointedly identified as “Elias, the Jew.” (Interestingly, in Act III, there is also a rival to Hoffmann named Schlemil.)

The current Israeli Opera production of Hoffmann is, in fact, the result of a trilateral collaboration with L’Opera de Lausanne and L’Opera Royal de Wallonie, Liege. The prime mover behind this realization, meanwhile, is Italian-born Director Stefano Poda, who also designed the striking set, as well as the exclusively all-black and all-red costumes, and even the lighting. Poda has done audacious work locally once before, staging the 2017 Israeli Opera performance of Charles Gounod’s Faust.

The scenery never changes throughout the very lengthy performance: three hours and 40 minutes, with two intermissions. When the plot lags, or the music gets too static, it takes patience to sit through the whole thing – and more than a few people did not last past Acts I or II.

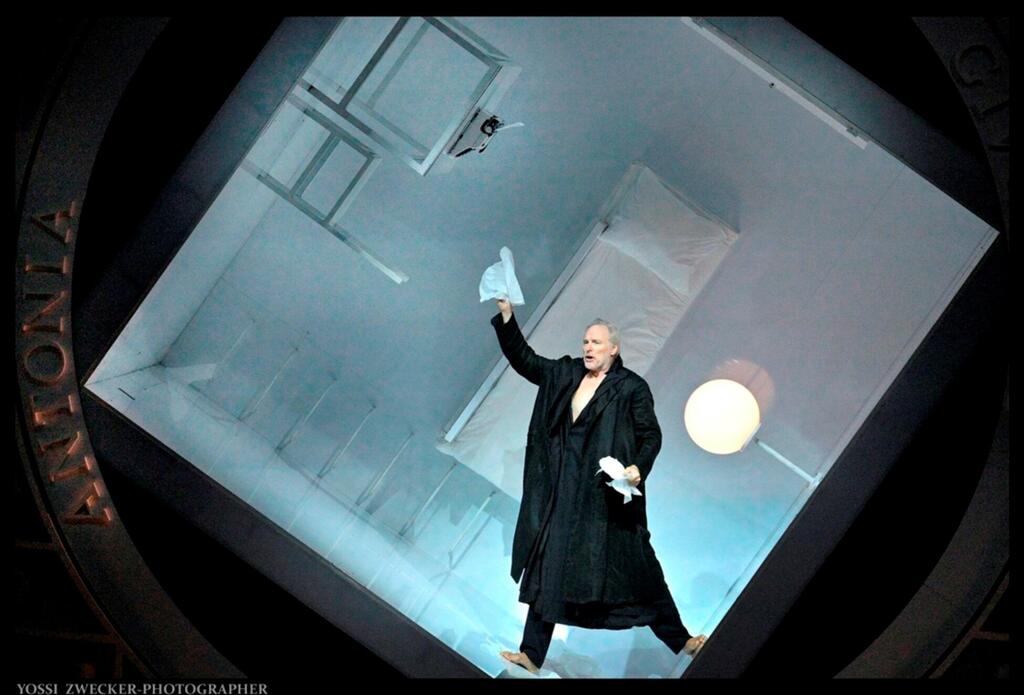

The permanently fixed scenery, if you will, was nevertheless cleverly enlivened in spots, when the back wall parted to reveal a rectangle with elements that moved. The most compelling instance was in the Prologue, when the lead character Hoffmann is enclosed in a square room that rotates, so that the artist has to keep his footing while the walls and ceiling become the floor – all this while singing, barefoot, and not missing a note.

It must be said, moreover — to Poda’s credit – that the rotating room brilliantly evokes the unsteadiness of a drunk, which by all accounts, was a condition in which Hoffmann frequently found himself. The barefoot state of the protagonist adds a certain degree of poignance to his circumstance – although it quickly becomes overdone, as Hoffmann remains barefoot throughout all the rest of the opera. (So, too, by the way, does his muse, a.k.a. Nikolausse, Hoffmann’s constant companion.)

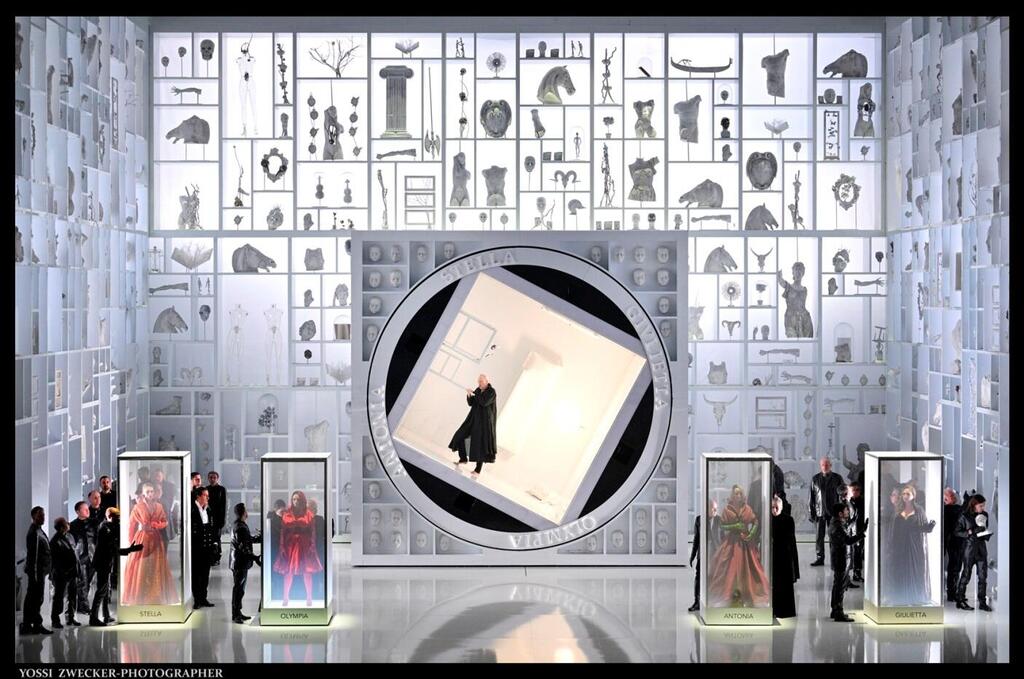

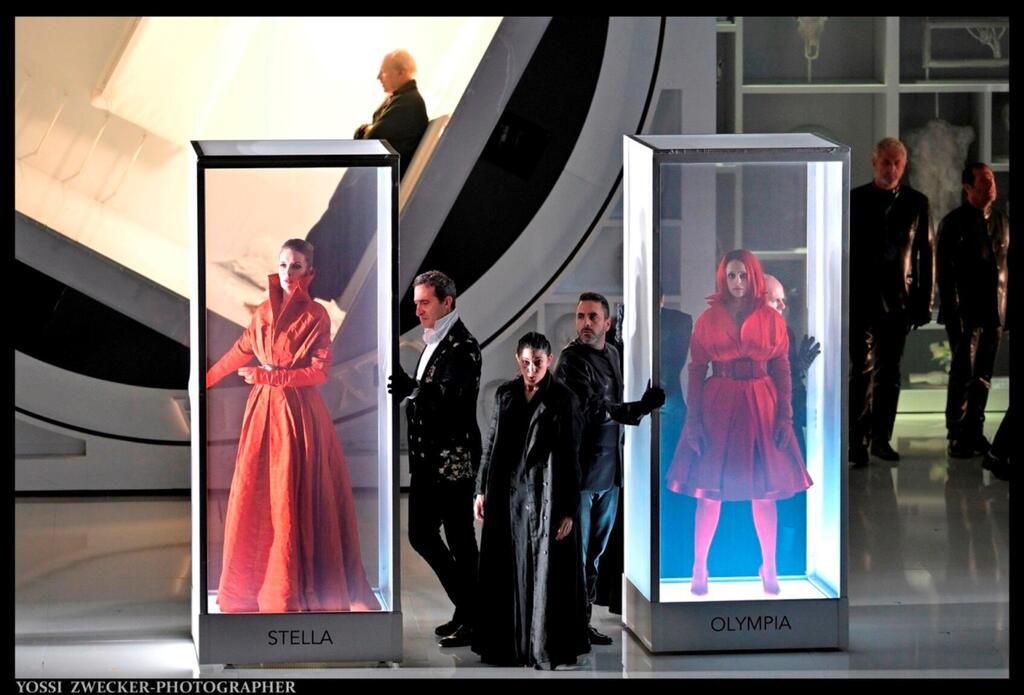

Alas, this was not the only puzzling aspect of the set design or direction. Too often, the floor was cluttered with meaningless bric-a-brac, with anonymous black-clad characters crawling around and lying on the floor examining the objects. At other times, these same figures were busy pushing around glass booths in which statues or dolls of women in red were encased.

These transparent cages did occasionally serve a worthwhile purpose – as in the case of Olympia the doll – but the good idea got a bit out of hand, especially when the rolling booths traversed the stage aimlessly.

Regardless, on the whole, bravura performances were turned in by the vocal artists – in a most unusual constellation: at the premiere, all the male leads were foreign talent, making their debuts in Tel Aviv, while all the female leads were members of the Israeli Opera company whom we have grown to know and appreciate.

The demanding role of Hoffmann was masterfully acted and sung by American tenor Charles Workman, while Italian bass-baritone Vito Priante excelled in his multiple roles of Lindorf, Coppelius, Dr. Miracle and Dapertutto. The third artist making his Israel debut is American bass Scott Wilde, in the major role of Crespel.

On the female side, Israeli sopranos Anat Czarny, Hila Fahima, Alla Vasilevitsky and Elinor Sohn played the roles of The Muse/Nicklausse, Olympia, Antonia and Giulietta respectively. One memorable moment was when prolonged applause erupted in the middle of Act I, after Fahima finished her stunning rendition of the aria “Les oiseaux dans la charmille” (often referred to simply as “the Doll Song”).

Naturally, with so many challenging roles in such a long production squeezed into such a short run, the leads must rotate – each alternating one night on and one night off. One may consult the complete cast schedule by date in order to learn exactly who is performing on any given evening.

One constant presence is the Israeli Opera’s Music Director Dan Ettinger, conducting the resident Israel Symphony Orchestra Rishon LeZion. There are not many purely instrumental interludes, or even much of an overture, but everyone will enjoy the musical accompaniment – and especially the strains of the famous barcarolle "Belle nuit, ô nuit d'amour.” Indeed, many of the highlights of this production are when the entire chorus gives full voice to songs that resound majestically throughout the auditorium.

The Tales of Hoffmann is scheduled to run through Friday afternoon, November 18 – a surprising matinee that will barely end before the sabbath commences. The next production of the season will be Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, an Israeli Opera favorite, in early to mid-December.