Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

When the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York approached Limor Tomer to head their new "Live Art" department, he told her that the role requires "tact, patience, and diplomacy."

More Stories:

Tomer couldn't hold back and laughed at him. "I told him, so that's why you're interviewing an Israeli?"

Tomer, originally from Ramat Hasharon, has been living in New York for several decades but feels "100% Israeli. "The Israeli attitude helped me throughout my career, but sometimes it's a double-edged sword. Sometimes it helps, and sometimes it sets me back," she says. "There are many stereotypes about Israelis in the industry, some are true and some aren’t, but it can’t be denied that we approach things differently than most, for better or worse," Tomer says.

One would expect a reasonable person receiving such an offer from the most important Modern-day Museum to jump on it without hesitation. But Tomer hesitated. "I’m very stubborn and very committed to things I care about. I don't give up, and if I hit a wall, I’ll find another way to reach my goal. After all, Israelis always find a way.” She says.

“So, when the director offered me the job, I told him that it didn't quite suit me. I simply didn't believe they were serious enough and were willing to commit to modern and contemporary. Live art isn’t like booking a finished piece of work for a fee. I told him he would have to invest a lot of money without being sure how it would turn out. So I asked him again and again if he was sure this is what he wanted and he said it was and assured me that he believed in me," she says.

11 View gallery

Julia Bullock in Perle Noir: Meditation on Josefine, Metropolitan Museum of Art

(Photo: Stephanie Berger)

Fighting for live art

Since then, for over a decade, Tomer has been at the head of the "MetLiveArts" department, bringing in astounding talents such as Sting and Patti Smith, while also presenting more avant-garde artists.

As the only Israeli ever to fill the role, Tomer is already used to being asked what exactly "live art" is, even by colleagues at the museum whom she finds difficult to convince such art has any value.

Limor Tomer: "What we do doesn't have a fixed value. It can be documented, but it's not the real thing. So we need to convince the art world that what we do is also considered to be curating art."

"We deal with performing arts - that means music, dance, actors, theater, and stage art - any artist who uses their body to create art, Tomer says. "It's not necessarily just choreographers or composers; it can also be table art, like the performance we did with Chef Yotam Ottolenghi that included a meal with long tables but was also a performance, based on an exhibition at the museum about the Crusaders in Jerusalem,” she says.

“When my colleagues talk about art, it's usually a sculpture, a painting, an object, or architecture. Something physical. What we do doesn't have a fixed value. It can be documented, but it's not the real thing. So we need to convince the art world that what we do is also considered to be curating art."

But Tomer doesn't take it personally: "Curators always strive to promote the importance of their art form. Everyone faces the challenge of persuading others about the significance of their work,” she says.

“There are hierarchies in this world, and everyone always has feelings of inferiority - those in modern art feel inferior to 19th-century painting and Renaissance art. It doesn't end there. Creating a lot of buzz is part of the challenge, but also part of the excitement," she says.

So, what is the actual difference between the "Live Art" department and the routine cultural events held in numerous museums around the world?

"The main difference between us and many other museums, like the Tel Aviv Museum of Art that organizes a concert series, is that we don't do something detached from the galleries. “Many museums hold performances simply because they have a venue that can be used. It satisfies a basic need for people, but it doesn't have an organic connection to what happens inside the galleries,” she says.

“In New York, there are plenty of performance halls - Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Radio City - it's not something people need more of. On the other hand, we offer added value. Things that can only happen at the MET," Tomer says.

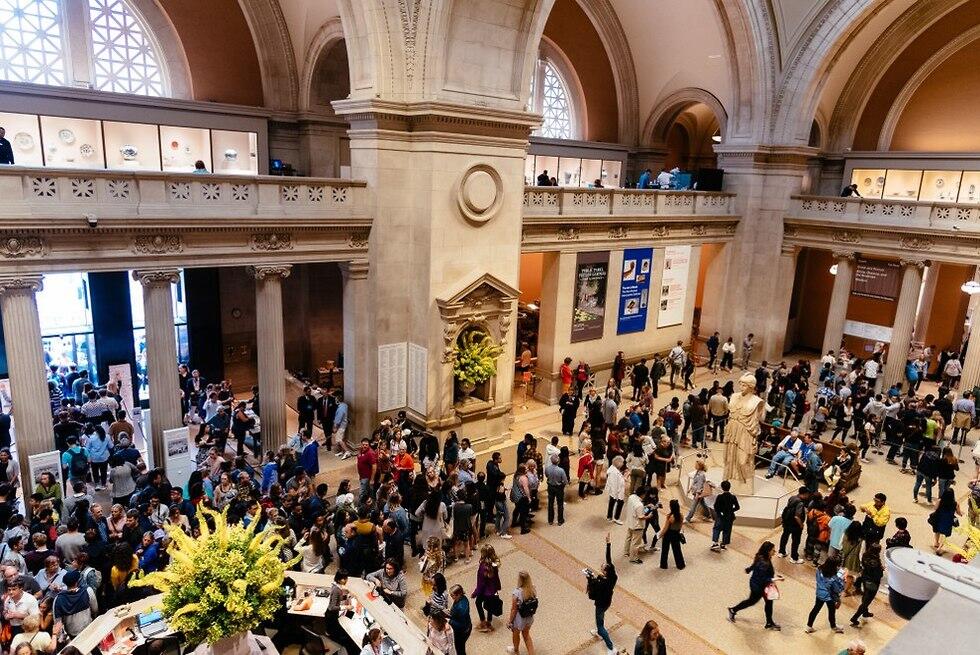

And in truth, many things can only happen in this enormous and resource-rich museum, which attracts over 6 million visitors annually. "That’s right, nothing in the world today compares to it," she says. "Not only museums in Israel but also the British Museum and even the Louvre.

"However, the expectations are high. The MET leads the way because it’s big and comprehensive, and my department is one of the smaller ones in the museum. Our part is small, but we collaborate with all the elements in the museum, and that's why our impact is significant,” she explains.

“We work with live artists, invite them to the museum, and provide them with all the resources they need to promote their art - and that’s truly an unparalleled opportunity. In fact, in recruiting me, the MET showed a very strong commitment to contemporary art and understood the trend of the past 100 years in which artists increasingly use live art to express their ideas and philosophy."

11 View gallery

Nikhil Chopra performing LANDS WATERS SKIES, Metropolitan Museum of Art

(Photo: Stephanie Berger)

'Everyone goes to the MET'

Before coming to the MET, Tomer worked at the Whitney Museum of American Art, another longstanding New York institution, but she says the two can’t be compared. "The power of the MET is that it speaks to everyone, unlike the Whitney, everyone goes to the MET. Most people in the world want to see Greek and Roman history and Impressionist art,” she says.

“They're not looking for some fringe artist from the 70s, and probably wouldn't buy a ticket for a solo exhibition downtown,” she adds. It's an audience that doesn't come with specific intentions. We hope that art will transcend barriers and speak directly to people’s hearts. “That's what has fascinated me so much about the MET – it’s universal and also historical. While the Whitney focuses on the past century in America, the MET goes back 5,000 years and encompasses everything."

Limor Tomer: "I can engage in a dialogue with art from anywhere in the world and from any period; one day in the Middle Ages, the next in ancient Egypt, and the day after in Babylon."

"To be clear," Tomer says, "Everything I know today, I learned at the Whitney Museum. It has a very important legacy. In the 60s and 70s, all the most important and respected artists exhibited in their galleries."

Tomer was the first performance curator of the museum's contemporary art department, and transitioning from Whitney to the MET was, in her opinion, “A very surprising transition. But now I can work on a much bigger canvas. I can engage in a dialogue with art from anywhere in the world and from any period; one day in the Middle Ages, the next in ancient Egypt, and the day after in Babylon."

And what about Israeli art?

"I don't have an agenda to specifically promote Israeli artists. I want to promote artists who are willing to take on the MET, and who have an appetite for it. Of course, I judge works based on the art they contain. “In general, I believe that artists are cosmopolitan. There are artists who come from all sorts of places, but they continue moving and showing their art all over the world.”

Tomer agrees to mention one Israeli artist who particularly interests her these days: Ofri Cnaani. "She deals with video, audio, and text, and her artistic performances are very inclusive, with subjects related to Israel and Judaism. I really love her,” she says.

Tomer was born in Ramat Hasharon to a mother who’s a Political Science professor at Tel Aviv University and Haifa University, and a father whose work in the aerospace industry, led the family on a relocation to New York.

Tomer, who excelled in playing the piano, was only 13 when she was accepted to Juilliard, where she remained until her master’s degree studies. After graduating, she experienced "a bit of a crisis with music, she says. "I realized that I find contemporary music more interesting than classical music. It's not that I don't love Mozart and Beethoven—I like to think about who they’ll end up being today. So, I also understood that I'm less interested in being on stage, but rather in helping contemporary artists reach a wide audience."

After finishing her doctorate in Art and Visual Aesthetics, she got her first job at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) where she worked in various positions and focused on contemporary performances of music, opera, ballet, and dance.

From there, she arrived at the Whitney Museum and eventually landed at the MET. During her journey, she met her husband, originally from Texas. "He doesn't speak Hebrew, and our daughter doesn't either. To this day, she's very angry with me for not teaching her at home, and rightfully so because I regret it a lot.”

Tomer has a simple explanation for her success and achievements. "I was always very focused on contemporary art. That became my expertise and niche." she says, "I don't separate life and work. The term 'work-life balance' is not something I grew up with. My work is my life. Every time I'm abroad, the first thing I do is look for new artists—what they're doing, where interesting works can be found—because that's life for me. When someone tells me they're looking for 'work-life balance,' I always think to myself they have the wrong job."

Goals for the future

However, with all the dedication to her work, Tomer still feels the presence of a glass ceiling in the industry. "While I don't feel a glass ceiling as an Israeli, I do feel it based on gender. There aren't many women museum directors. There are plenty of department heads and curators, but when it comes to the top positions, it doesn’t happen. And not only in my industry but in almost all.”

Is your next goal managing a museum?

"No, I love working directly with artists, and I'm exactly where I belong right now. Managers need to work with employees, and that's not what I want to do. My current goal is for us to achieve success effortlessly knowing that live art is the way forward. Not only at the MET, but other museums like the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.”

If the Tel Aviv Museum of Art called you to lead it, would you take the job?

"I’d consider it. But in any case, I’d try and help them figure it out. All they need is the motivation and ambition to do it. There are so many talented people in Israel including artists, curators, and administrators – who just need a place to show what they can do.”

According to Tomer, her field faces challenges like many others. “Raising funds,” she begins, But also, "the challenge of the live artist to deliver their message from the stage into the gallery itself,” she explains.

"Today, leading museums are increasingly paying consistent attention to their visitors, and that is a very positive trend," says Tomer. "In the past, curators felt they had all the say in the gallery. Today, they're more interested in engaging with the audience, attracting and involving them,” she says.

“Many critics say it lowers the museum’s standards, that it's dumbing down, that it's become commercialized, but it's not necessarily the case. If you use this language, you create an artificial barrier between those who enjoy art and those who aren’t 'sophisticated' enough to participate in it. Curators simply need to work a little harder to attract a broader, non-professional audience.”

Tomer says that today, the new trend of appealing to the audience extends beyond museums: "For example, in concerts - today people clap between movements of a symphony. It used to be a real taboo; you were considered uncultured or out of place if you clapped. Today it happens a lot, and conductors allow it. What's important is to enable audience engagement, to make them feel included. That's the goal.”

What was your favorite performance you brought to the MET?

"The choreography of ballet dancer Silas Farley. I really wanted him to perform here, so I took him to the MET for several hours hoping that something would ignite his creative juices. After 8 months, he suddenly came back to me with an idea - he wanted to create a piece using songs relating to ghosts and souls. A work that would take the audience from loneliness to community. I thought about it for a while and told him I thought the loneliest community can be found in a prison, and we could find prisoners who are musicians and ask them to compose modern works for us,” she says.

“We traveled to San Quentin prison in California for a year and held auditions. There were amazing talents - singers, guitarists, and even a full band. We selected pieces of music and songs performed by people who would probably never leave prison - it was amazing. “We brought the songs to the MET, and Farley choreographed a dance to their songs. It touched on so many historical and contemporary themes in such a sensitive way.”