Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

"I think the sun had risen. I don't remember if the trees bloomed or not, but I assume so," thus described Dr. Thomas Harvey the morning he made his way to the hospital in Princeton, New Jersey, to perform a post-mortem autopsy on the body of Prof. Albert Einstein, who is considered the smartest man in the modern era.

Read more:

What Dr. Harvey meant to say, in his cynical way, is that it was seemingly another normal day. But in fact, it was the day that changed his life forever and also, ultimately, taught humanity a fascinating lesson about the nature of genius.

A few hours earlier, on April 18, 1955, around 1am, Einstein was pronounced dead at Princeton Hospital at 76. Somehow, between that time and dawn, the phone rang at the home of Dr. Harvey, the chief pathologist of the hospital. That phone call found him at a very specific point in his life, with ambitions to leave a mark on the world of science.

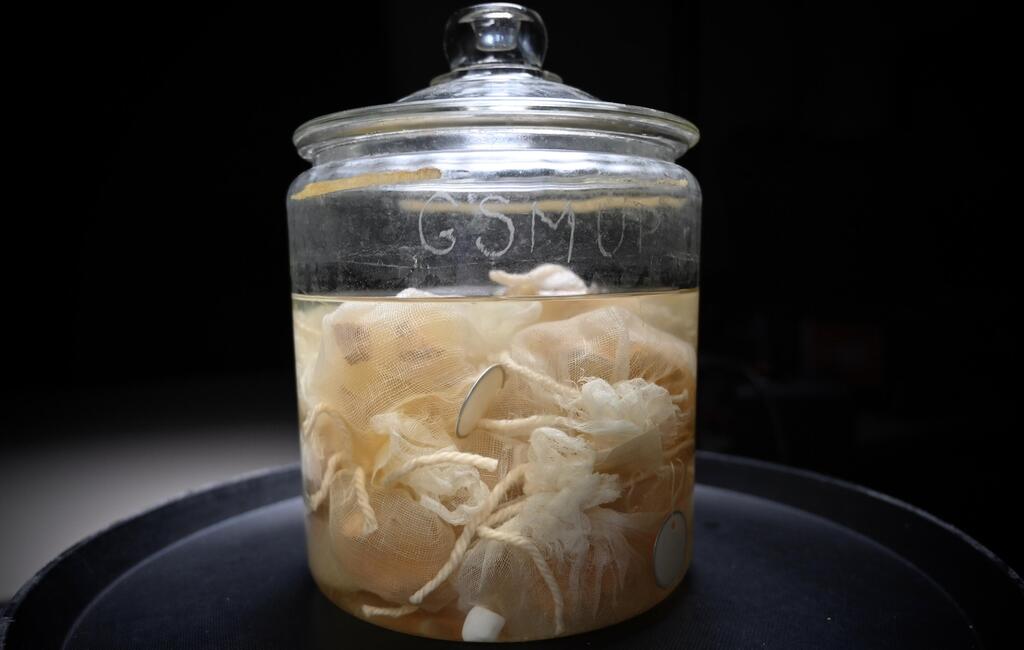

It's not exactly clear when Harvey identified the opportunity to make history, but his following steps led to a series of events that ranged from fascinating to absurd to uncomfortably striking. This was Harvey’s journey with a very important organ, stored in a jar with preservative fluid and a screw-on lid.

Harvey, the pathologist who performed the autopsy on Albert Einstein's body, stole Einstein's brain in the hope that he would be able to uncover the source of his genius and become a star. Instead, his life unraveled as he moved the brain from place to place in cardboard boxes for the next 50 years.

These astonishing events are the subject of a new film, The Man Who Stole Einstein's Brain. The new film, directed by Michelle Shephard (53 minutes, Canada, 2022), reveals archival materials and rare recordings of Harvey, showing how his hubris, over the course of decades, led to the ruin of his professional and personal life, and how his journey quickly became a delusional obsession.

Over the years, he shared tissue samples with leading pathologists around the world, trying to find answers to questions that have occupied humanity, but these provided very few new discoveries, as it turned out that the whole organ was more impressive than the sum of its parts.

Year of wonders

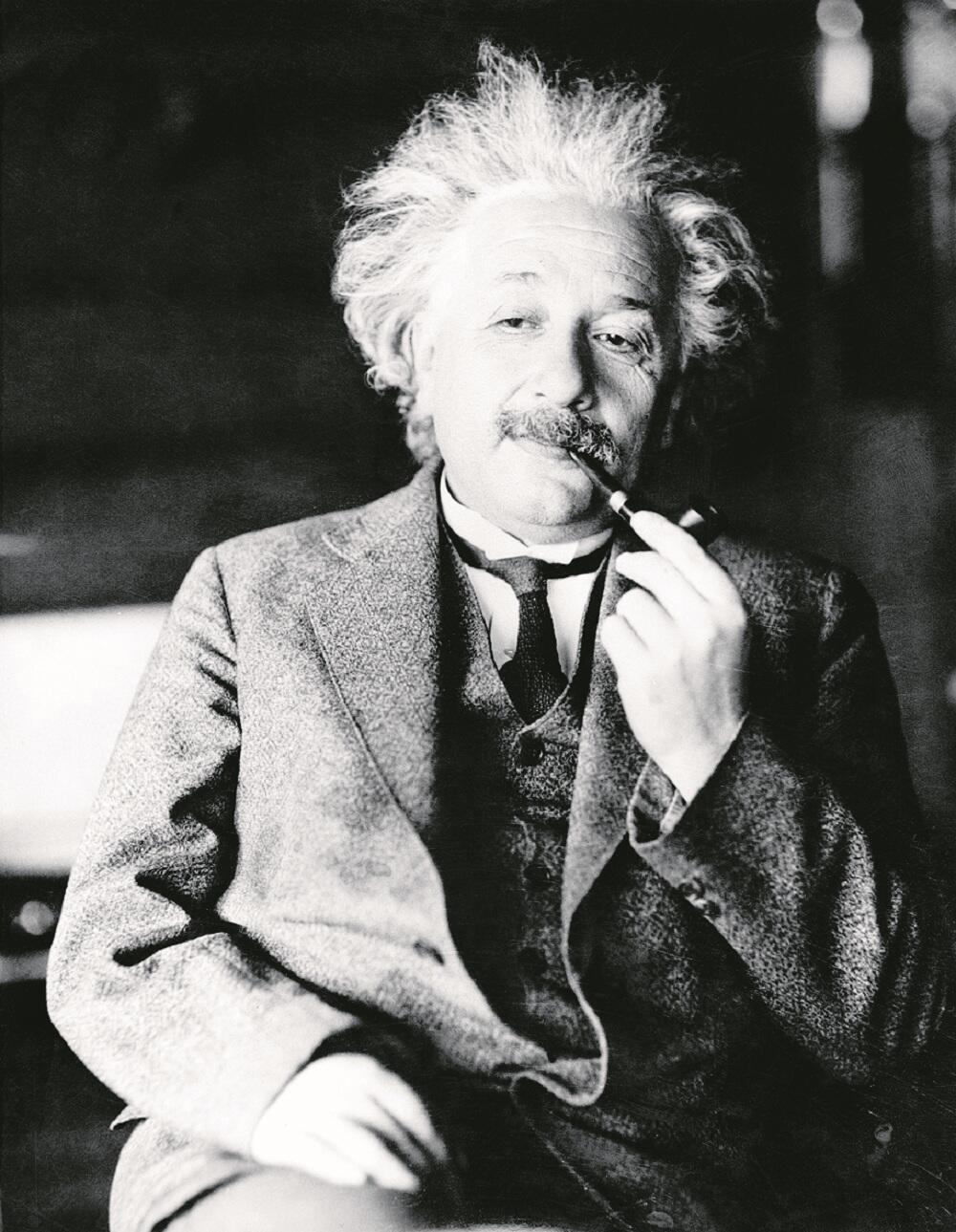

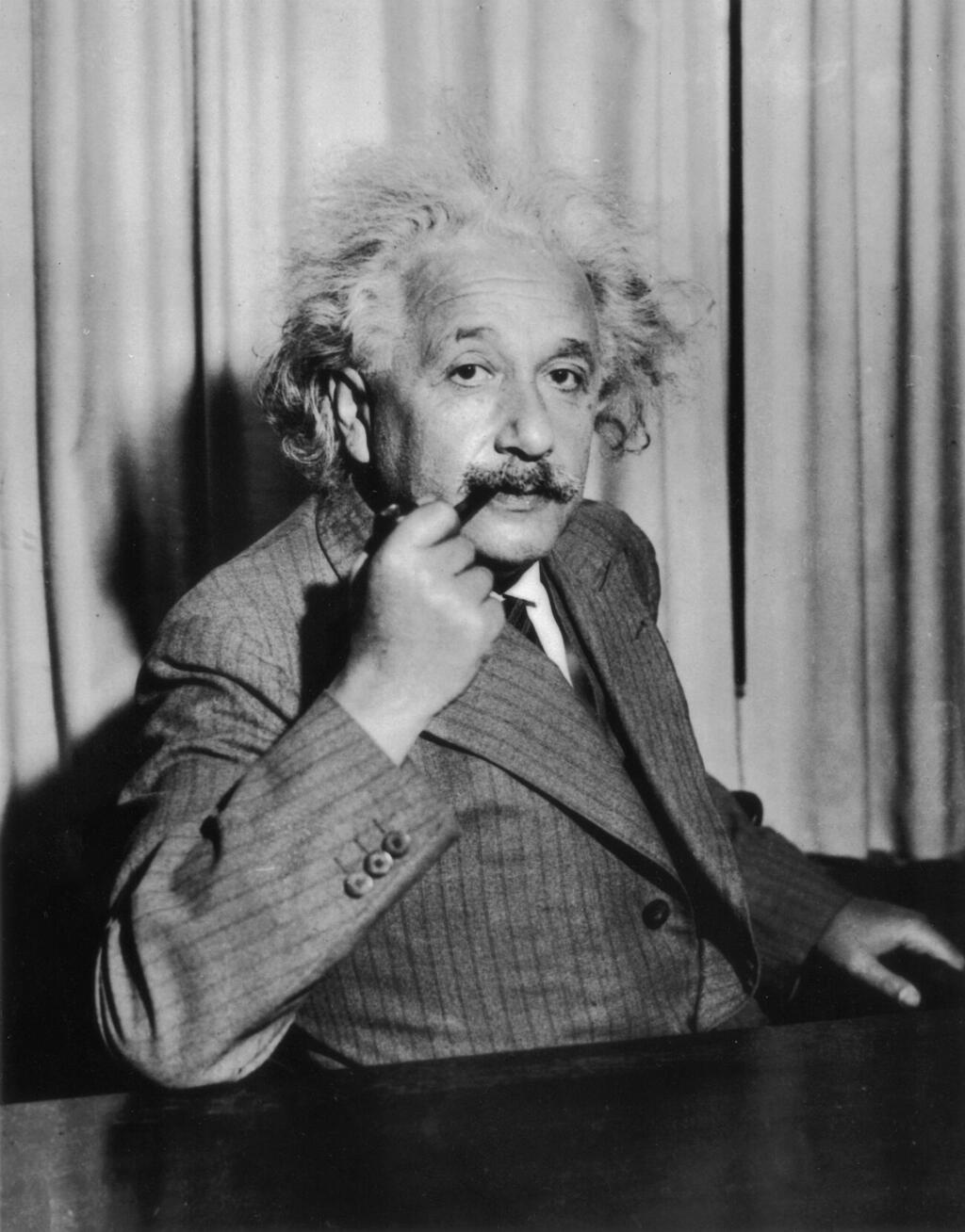

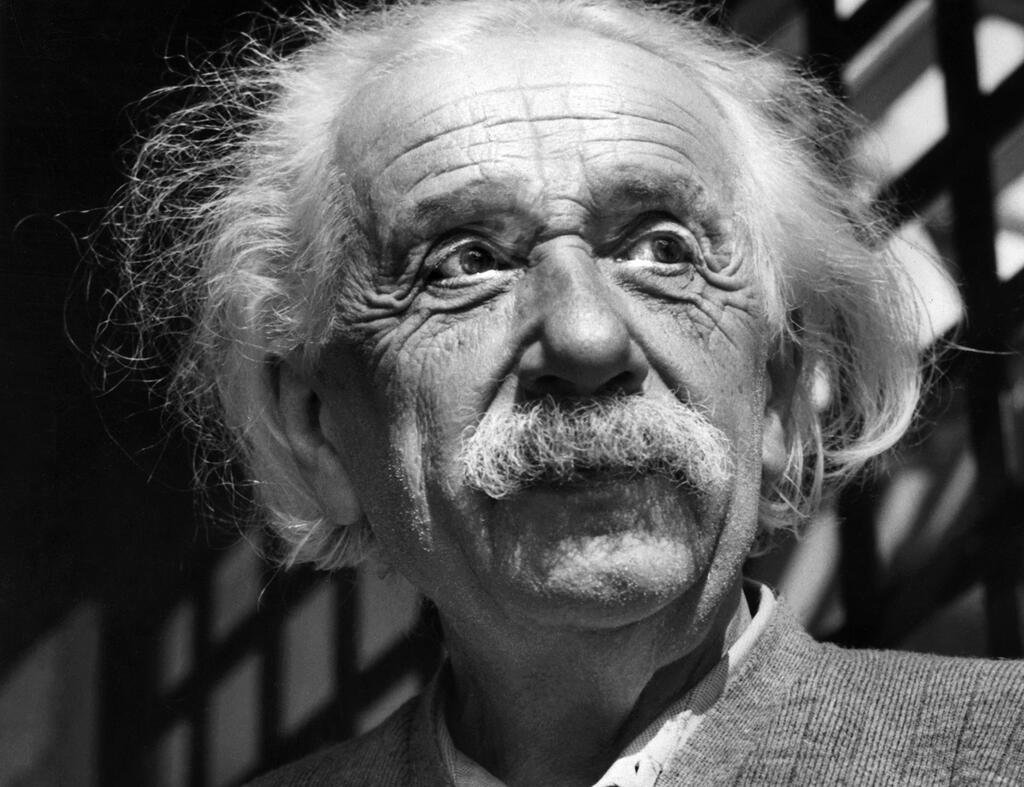

Einstein, arguably the world's most famous Jew and a name synonymous with genius, was born on March 14, 1879, in the city of Ulm in Germany. During his childhood, his family moved to Italy, where he completed his high school education and continued to study to become a mathematics and physics professor at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic.

After receiving his diploma in 1901, he also became a Swiss citizen and was appointed to a position in the local patent office. From that point on, his progress was meteoric.

In 1903, at the age of 24, he already held a Ph.D., and in 1905 he published four important and groundbreaking papers in a scientific journal on physics. The extraordinary significance of these papers earned that year the title “annus mirabilis” or “the year of wonders.” Meanwhile, various universities around the world began competing with each other to offer professorships to the young genius.

In 1915, Einstein published his most famous theory, the theory of relativity, changing the way humanity understands the relationship between time, space and matter. In 1922, at the age of 43, he already won the Nobel Prize in Physics.

In his personal life, Einstein was married twice and had three children. His first daughter was born to his wife Mileva Marić before they were married, but Einstein never met her. It is believed that she either died from illness or was given up for adoption. In 1903, Einstein and Marić married and had two more children. After their marriage ended, he married his cousin Elsa Löwenthal in 1919.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, he was in the U.S. on a work-related mission. The Nazis revoked his citizenship and confiscated his property, and Einstein remained with Löwenthal in America. In 1940, he became an American citizen.

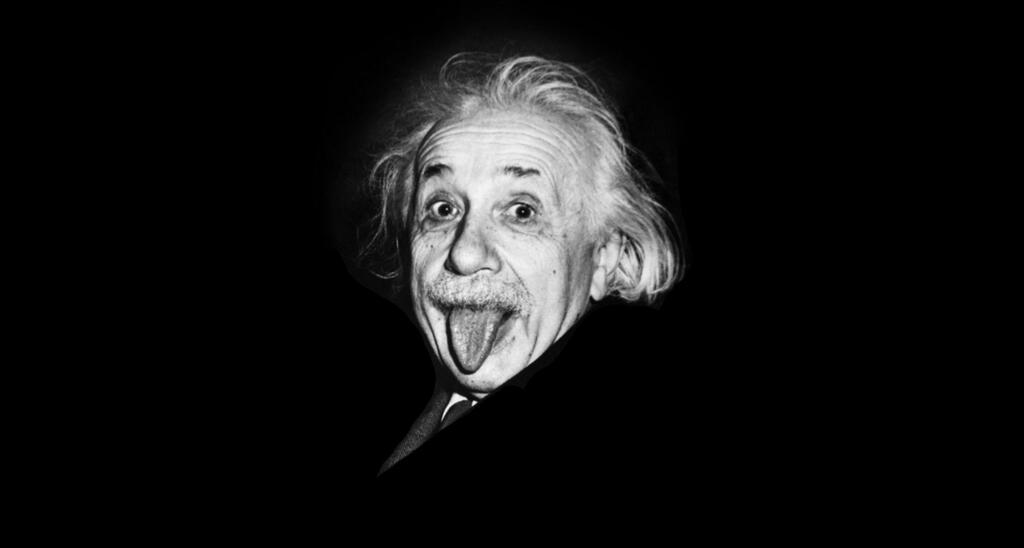

Einstein held a position as a professor of physics at Princeton University, where he was considered an extraordinary figure—a man with minimal social skills who often wandered around the campus with disheveled hair, pajamas and slippers, and who had an unfailing sense of humor.

And let's not forget the Israeli angle: David Ben-Gurion offered the Jewish scientist the role of the second president of the State of Israel, but he declined. Either way, Einstein supported Zionism and worked diligently for the establishment of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

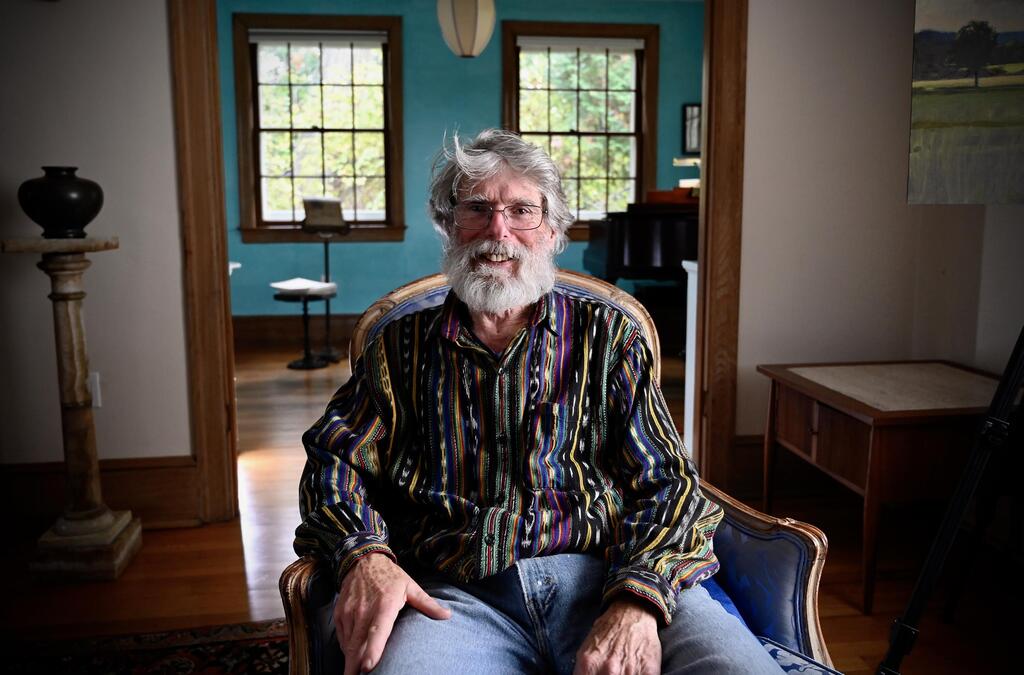

Dr. Harvey Einstein never met Albert Einstein. In fact, their first “encounter” was in 1955, after Einstein's death, when Harvey performed an autopsy on his body. Harvey was born into a family that emphasized striving for excellence. His great-grandfather was a doctor, and his grandfather was a judge. He was expected to follow a similar path and choose either medicine or law for his studies.

He studied medicine at Yale University. During his studies, he contracted tuberculosis and moved to a sanatorium, where he met his first wife, Eloise. A short time after their release from hospitalization, the two married and later had three sons.

The outbreak of World War I was difficult for Harvey, who belonged to the Quaker community, a Christian sect that believes in pacifist values. Instead of fighting on the battlefield, he volunteered to serve in a military pathology lab.

After the war, Harvey quickly realized that pathology was a field where the demand for doctors was higher than in pediatrics, and with the experience he gained in the military, he was put in charge of post-mortem examinations in a pathology lab. This position would change his life.

Surrounded by human organs and body parts

In an interview for a documentary (available on YES VOD, HOT and STING TV), Robert, Dr. Harvey’s son, admits that he had an unusual childhood. He says he grew up surrounded by human organs and body parts. There was even a time when his father invited him to watch an autopsy.

Robert doesn't know quite what to say about that experience. His father always dreamed of making a significant contribution to science and society. He conducted experiments in their home garage and even tried to find a cure for cancer at one point.

However, the defining moment in Dr. Harvey's life occurred in the early hours of April 18, 1955. That's when the phone rang at their home. On the other end was Einstein's doctor, Guy Dean, saying, "Tom, you need to come here. Einstein passed away last night, and we need you to perform a post-mortem autopsy."

Robert recalls that the family was sitting around the kitchen table when this news broke out, and he had no idea what was about to happen.

Harvey made his way to the hospital from his home on Jefferson Street, just like he did every morning. The sun rose as usual, but Harvey likely understood that this was no ordinary morning. All his aspirations and the journey of his career led him to this day.

He started performing the autopsy as he would any other, following the regular protocol. Harvey acknowledged that he was dealing with the body of a distinguished person, but he did not deviate from his standard procedure, which typically started with the heart and moved on to the lungs and so on.

However, Harvey then took an action that was outside of standard protocol. He used a saw to open the skull, reached in, and took out the brain. From that moment on, this human organ became the holy grail of his scientific ambitions.

It's unclear how the media found out about this, but the next day Einstein's family read in the New York Times that their relative's brain had not been cremated along with the rest of his body. Robert says that he understands the family was very concerned about what his father had done, but he trusted his father's judgment.

Somehow, Harvey managed to get permission from Einstein's estate manager to examine the brain. He assured that the organ would only be used for scientific research and that any publications about it would solely appear in scientific journals, not becoming a subject of public fascination or misguided speculation. However, the reality was somewhat different. Even 68 years later, Einstein's brain remains a partially unresolved mystery.

‘I wanted to take it with me to school’

As for preserving a human brain, the method involves injecting formalin into the large blood vessels. After that, the organ is placed in a jar filled with formalin. Dr. Harvey followed this procedure before dividing the brain into about 240 pieces and storing them in separate containers.

He then traveled to distribute these pieces among various scientists, hoping they would undertake the challenge of investigating this rare find. It turns out, however, that there was not a great deal of immediate interest in the research.

The American military did express interest in the brain, but Harvey, a pacifist, was not willing to hand over the brain of the late pacifist scientist to the armed forces. Meanwhile, he became something of a local celebrity.

But his personal life started to unravel. Rumors that he was having an affair with a lab worker reached his wife. The couple separated and reconciled several times until they eventually divorced. Around the same time, he also left his pathology lab in Princeton. It's possible that the rumors contributed to this decision. What is known is that he took Einstein's brain with him.

Harvey's second wife was a researcher at a neuropsychiatric institute in New Jersey, where he began to work. He adopted her children, and in their shared home, in a basement office housing with a wooden desk and dozens of books, Einstein's brain was stored in a transparent jar.

According to their daughter, they were not allowed to discuss it. She once asked if she could bring it to school, but the answer was “no.” Whenever she had friends over, she would take them down the stairs to see it.

Harvey went through his second divorce at 60. The manager of Einstein's estate tried to keep tabs on him and sent him letters inquiring about the research he had committed to publish. The media also didn't forget about the unusual event. Steven Levy, a writer for Wired magazine, was assigned by his editor to track down the celebrated cerebrum.

Levy first reached out to the manager of Einstein's estate, who aggressively turned him away. After extensive journalistic effort, Levy was able to locate Dr. Harvey in Wichita, Kansas.

Harvey welcomed him at the door, and both men were tense. They moved from the lab to Harvey's office for a conversation. Harvey appeared to be quite nervous and seemed hesitant to speak on the subject. Levy felt that he was hearing things that hadn't been heard in 20 years, but Harvey did not answer one key question: where was the brain?

In the end, Harvey acknowledged that he had some tissue samples. The story was featured prominently in the media, making headlines once more. Levy found himself in high demand for interviews.

Even Johnny Carson touched on the subject during his show's opening monologue. He humorously mentioned that parts of Einstein's brain had surfaced in a lab in Wichita, Kansas, and the remains were kept in a jar. What convinced the scientists that it was indeed Einstein's brain was a joke that one morning, they found the brain looking for the first bus leaving Wichita.

Try declaring this to customs

Following the renewed media interest, Tom Harvey's life changed dramatically. Reporters gathered on his lawn, hoping to get an interview with him. He was not pleased with this sudden fame. Virtually overnight, he became known as "the man who holds Einstein's brain," and his actions raised many questions among the public.

The most significant of these was why nearly three decades had passed without him publishing a single scientific paper based on the findings he had obtained.

One of the world's leading scientific journals, Science, published a photo from Levy's article that showed part of the brain being held in a juice box.

Meanwhile, in a lab in Berkeley, someone drew the attention of brain researcher Marian Diamond to the matter, knowing she would take special interest in Einstein's brain.

Diamond's research focused on how the human brain undergoes changes over a lifetime and the influence of the environment on these changes. She discovered a type of brain cell called a glial cell, which essentially acts as a caretaker for neurons. The more glial cells there are, the better the neurons function, allowing the brain to develop.

Upon seeing the picture of the brain in the juice box, the scientist wondered how many glial cells Einstein had. When she reached out to Tom Harvey, he was relieved, as the scrutiny around his possession of Einstein's brain had intensified.

He immediately went to his jars, which contained four pieces of the brain, placed them in a mayonnaise jar, and sent them to Berkeley. Diamond's research found that Einstein had 73% more glial cells than the average person.

Diamond's research was published in the 1980s but faced severe criticism. It was suggested that the scientists involved in this brain research were more driven by the desire for publicity than by the aim of achieving scientific breakthroughs.

An odd documentary on the matter was released several years later. It told the story of a Japanese physicist who was deeply interested in the late Jewish scientist. He befriended Harvey, and in an unsettling scene that also appears in the new documentary, Harvey is seen presenting pieces of the brain to his Japanese guest, who reacts with awe.

The Japanese scientist, looking visibly excited, asks if he can have a small piece. Harvey takes a butter knife and cuts off some pieces of the brain in a scene not recommended for the squeamish.

The Japanese scientist sounds appreciative as he says, "Oh, thank you very much." Thus, the story of Einstein's brain took a somewhat grotesque turn, which continued when Harvey later became acquainted with British writer William Burroughs, who primarily wrote about his experiences with psychedelic drugs.

The story took another twist when a Canadian researcher named Sandra Witelson entered the picture. She had a large collection of human brains and one day received a fax asking if she was willing to study Einstein's brain.

Harvey packed the brain in the trunk of his Dodge and drove to Canada. Upon crossing the border, he tried to declare his unusual cargo to customs. When asked if he had anything to declare, Harvey thought they wouldn't believe him if he revealed what was actually in his trunk, especially since they didn't even ask to see it. He transferred part of the brain to Witelson, who was quite excited to hold the brain of the smartest man in the world.

Journalist Caroline Abraham, author of the book Possessing Genius, explains that science aims to be objective and rise above human weaknesses, but it can't be, as it is conducted by people who are inherently flawed.

Witelson focused on Einstein's prefrontal cortex, where she discovered anatomical abnormalities. Her research showed that the width of Einstein's brain from left to right was 15% larger compared to a control group.

According to Abraham, Witelson found that a specific groove in Einstein's brain differed from those in other brains. The regions separated by this groove are involved in mathematical reasoning and spatial visualization, which aligns with how Einstein described his thought process. He didn't think in numbers or conventional mathematical terms when conducting thought experiments; instead, he was able to vividly imagine himself riding on a beam of light. When Witelson completed her research, she concluded that she had found what made Einstein's brain exceptional.

Years later, Dr. Harvey would say that he had no regrets about preserving Einstein's brain for such an extended period. He acknowledged the significant responsibility he carried, but his full motivations remain unclear to this day.

Harvey passed away at the age of 94 in the same medical center in Princeton where he had initially removed Einstein's brain. Even after his death, he remains an enigmatic figure, and even the latest documentaries have not entirely unraveled his story. The ultimate fate of Einstein's brain and its current location has never been given a definitive answer.