Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Permafrost soils possess remarkable preservation capabilities due to their low temperatures. About four years ago, a remarkably well-preserved specimen was discovered on the banks of the Badyarikha River in the Sakha Republic, a northeastern region of Russia bordering the East Siberian Sea in the Arctic Ocean.

This finding provided a rare opportunity to examine an extinct predator that roamed Eurasia during the Late Pleistocene, as reported by LiveScience.

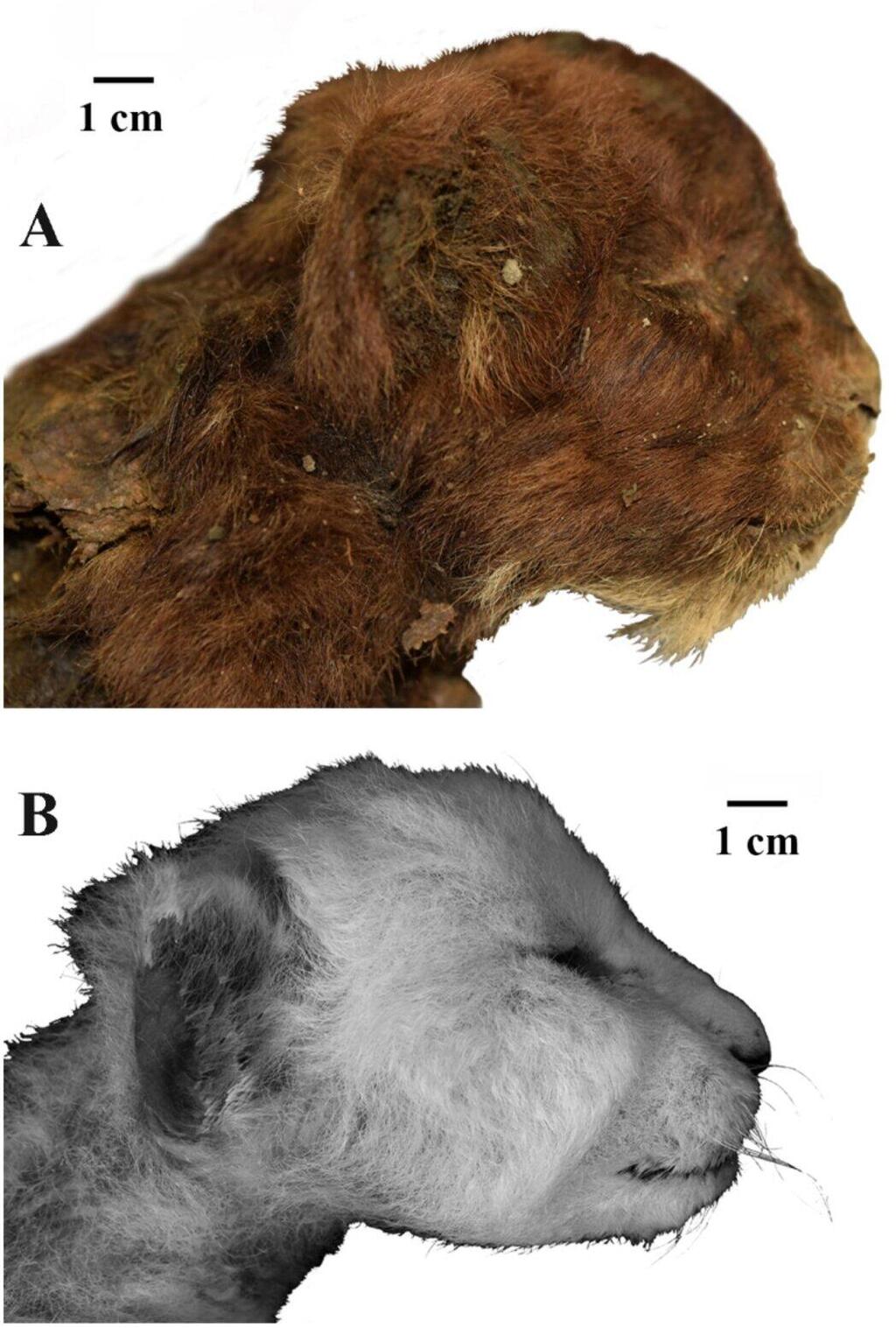

The specimen is a cub with thick, dark brown fur. Its paw structure was adapted for walking in snow, featuring sharp, curved claws similar to those of modern cats. A team led by the Borissiak Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences identified it as a cub of a Homotherium—a member of the saber-toothed cat subfamily, which became extinct after the last Ice Age.

The cub, which died at least 35,000 years ago, is attributed to the species Homotherium latidens. This is only the second known evidence of this species from the Late Pleistocene in Eurasia, following the discovery of a lower jaw in the North Sea area several years ago.

In a study published in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers conducted radiocarbon dating, morphological analyses, and tomographic studies of the mummified cub, comparing it to modern lion cubs of a similar age. The cub's remains, preserved in ice, include its head and upper body, as well as part of its pelvis and limbs.

The Homotherium cub exhibits significant anatomical differences from modern lions, including a more massive neck, elongated forelimbs, smaller ears, and a mouth capable of opening wider. Its paw structure was adapted for navigating snowy environments (broad paws without the pads found in today's cats), along with its thick fur, suggesting it lived for extended periods in cold climates and developed hunting strategies very different from those of contemporary big cats.

Comparative measurements by the researchers indicated that the skull and forelimbs of the Homotherium cub are relatively larger than those of a lion cub of a similar age, confirming that the extinct species had its own unique developmental path. Notably, one of the unique findings of the study on the mummified cub was that all identified traits were present from a young age—just three weeks old—and not only in older individuals.

Historically, species of Homotherium, including Homotherium latidens, roamed across Eurasia, Africa, and America millions of years ago until they became completely extinct. Most Homotherium fossils dated to the Late Pleistocene have been found in North America, with over 30 sites yielding samples of the Homotherium serum species.

Genetic analyses have since revealed that the Homotherium latidens species from the North Sea is genetically identical to the Homotherium serum species. The mummified cub discovered about four years ago in Siberia significantly expands the known geographic range of the species it belonged to, providing valuable insights into its physical characteristics and adaptations to the environment in which it lived.

Researchers plan to continue in-depth analysis of the anatomical features of the mummified cub, which may further illuminate the animals that roamed the Earth so many years ago. It is noteworthy that this is not the first time a well-preserved ancient mammal has been discovered in Siberia, as the region's cold and dry conditions make it an ideal place to find complete fossils from ancient times. The dry air desiccates the animal's soft tissue, and the freezing cold creates a perfect time capsule for research, even after many years.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: