Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

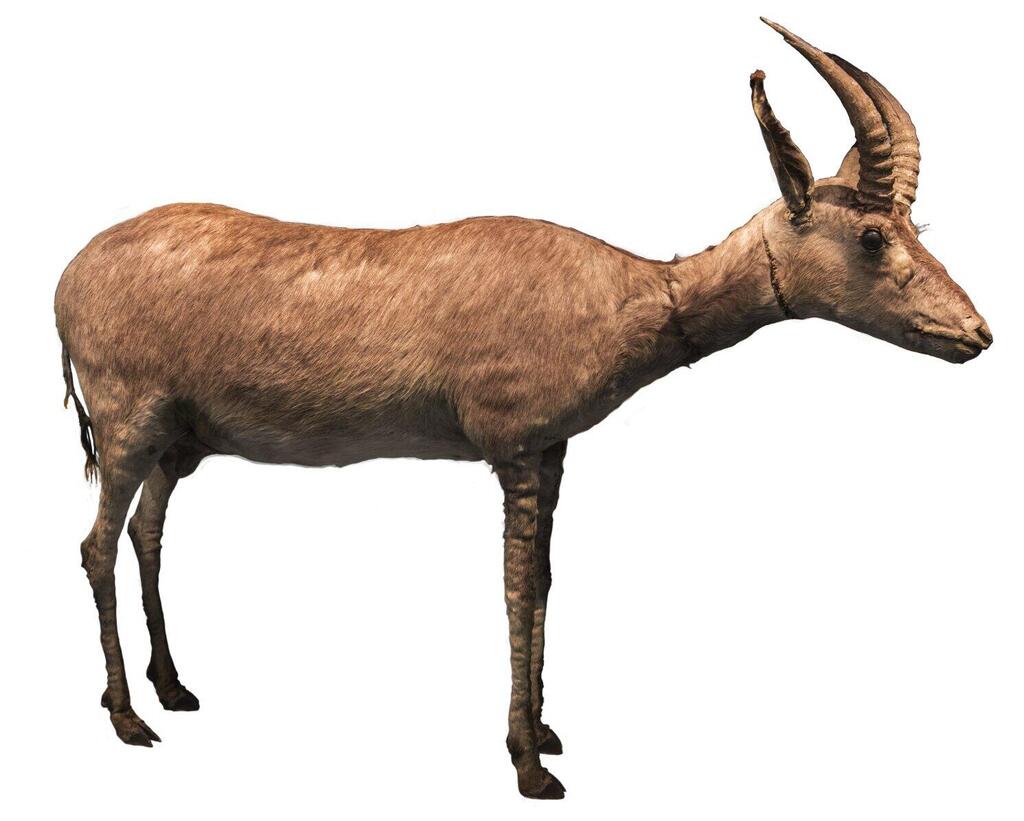

The blue antelope (Hippotragus leucophaeus), also known as the bluebuck or blaubok, was first documented in 1719 and classified under the subfamily Hippotraginae by the German zoologist Peter Simon Pallas in 1766. Less than 40 years later (by 1800), it went extinct, resembling closely related species like the black wildebeest (gnu) and the roan antelope.

It received its name due to the color of its fur, described as a color between grayish-blue to slate-gray. These antelopes were especially endemic to western South Africa, but archaeological evidence suggests they were once more widespread, even in eastern regions.

With the arrival of the Dutch settlers in the Cape of Good Hope, there was a drastic decline in the population of these rare antelopes, which was already small. The establishment of settlements, expansion of agriculture, spread of livestock diseases, and the introduction of firearms by new settlers rapidly led to the extinction of the remaining blue antelopes, with the last specimen recorded in 1800.

In a recent study published in the Current Biology journal, a team of evolutionary biologists from the University of Potsdam, led by Dr. Michael Hofreiter, successfully extracted high-quality DNA from a museum specimen at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, one of five historical samples of the blue antelope approved for ancient DNA analysis.

3 View gallery

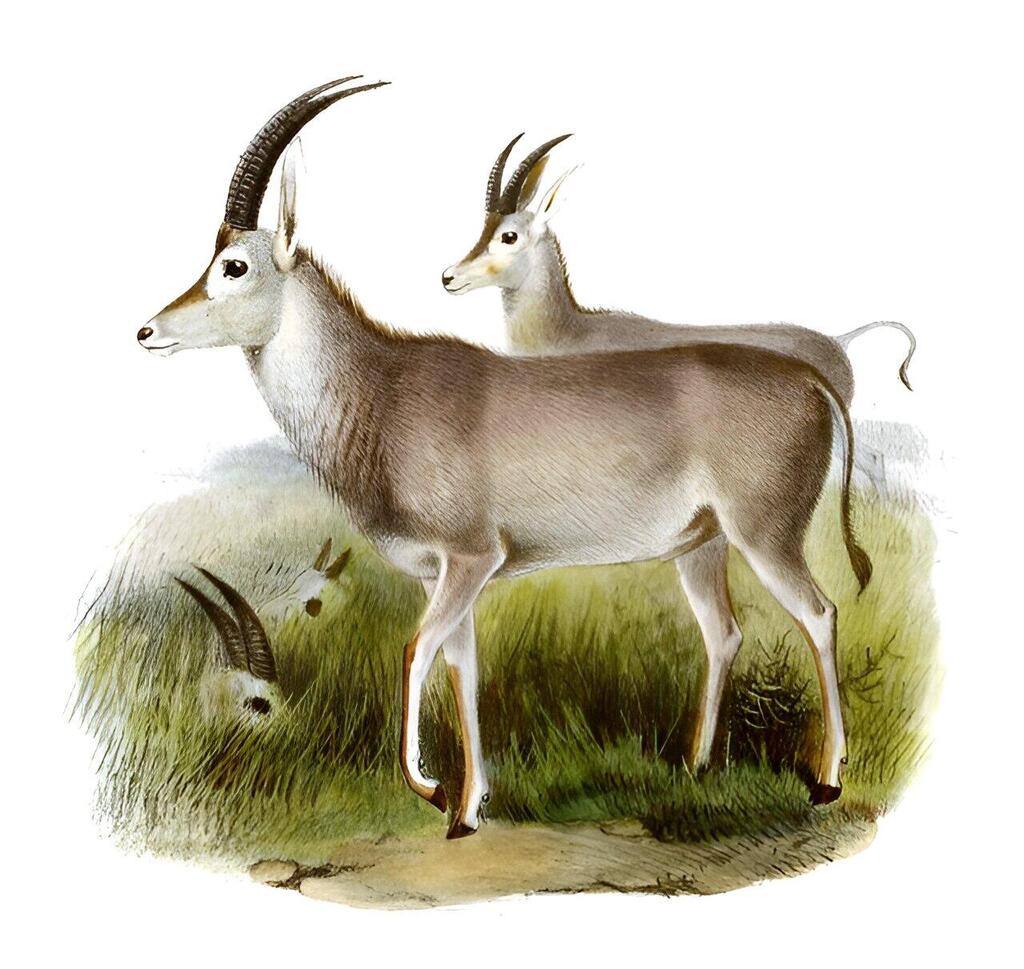

Blue antelope (Hippotragus leucophaeus)

(Illustration: Biodiversity Heritage Library, P. L., Thomas, O. The Book of Antelopes, vol. 4. – London: 1899–1900. Pl. LXXVI)

Low genetic diversity and a small population size are generally considered disadvantages as they may hinder a species' survival and adaptation to environmental changes. However, Dr. Hofreiter emphasized that the blue antelope had a small population size for thousands of years until its extinction around 1800. Long-term population size analysis showed that climate fluctuations during the Little Ice Age did not significantly impact its population, which was unexpected for a large herbivore, suggesting that such environmental changes were unlikely to affect its food sources.

Therefore, researchers concluded that species can survive for extended periods with a small population size as long as they are not exposed to various threats, such as the sudden human impact during the European colonization of South Africa in the 17th century, which played a central role in the extinction of the blue antelope, whose distinguishing feature was its two long and heavy horns shaped like a twisted sword.

During the DNA analysis, two genes responsible for the blue antelope's coloration, which gave rise to its name, were identified. This was made possible through the use of a novel computational analysis tool developed by Colossal Biosciences, a biotechnology company primarily known for its attempts to revive extinct animals.

"As part of Colossal's continued focus on ancient DNA, genotype to phenotype relationships, and ecosystem restoration, we were honored to collaborate on the groundbreaking work of Professor Hofreiter and his team. The research objectives for the project allowed our teams to work together applying some of the latest Colossal ancient DNA and comparative genomic algorithms to learn what truly made the blue antelope the unique species it was," said co-founder and CEO of Colossal Bioscience Ben Lamm.

This research not only shed light on the extinction of the blue antelope but also contributed to understanding the broader impacts of humans on wildlife. The findings of the study may help understand how human actions can disrupt long-term natural balances, leading to irreversible changes in biological diversity. The story of the blue antelope, which survived the Ice Age but not the intrusion of humanity in its territory, serves as a poignant reminder of that.