Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The Dead Sea is a highly dynamic system, with its water level dropping by about one meter annually for over 50 years. Disconnected from major tributaries and losing vast amounts of water to evaporation due to drought and heat, the surface has sunk to approximately 438 meters (1,437 feet) below sea level.

This decline has far-reaching consequences, particularly on groundwater levels, which are becoming harder to access. For years, Dr. Christian Siebert, a hydrogeologist from Germany’s Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research, has studied how the region’s groundwater dynamics are changing. His latest research, published in Science of the Total Environment, uncovered chimney-like vents on the Dead Sea’s floor emitting a plume resembling white smoke.

“These vents bear a striking resemblance to the black smokers found on oceanic ridges, although the systems are entirely different,” explained Dr. Siebert.

A multidisciplinary effort

Dr. Siebert and his research team, drawn from 10 institutions specializing in mineralogy, geochemistry, geology, hydrology, remote sensing, microbiology, and isotope chemistry, conducted a deep analysis of the phenomenon.

While black smokers at oceanic ridges release hot, sulfide-rich water at depths of thousands of meters, the Dead Sea vents expel highly saline groundwater through the lakebed.

The researchers found that groundwater from surrounding aquifers infiltrates the Dead Sea’s thick, salt-rich sediment layers, dissolving deposits primarily composed of the mineral halite. This process flushes the dissolved salt into the lake, forming brine plumes.

“Because the brine’s density is slightly lower than the Dead Sea’s water, it rises like a jet,” said Dr. Siebert. “It looks like smoke, but it’s actually salty liquid.”

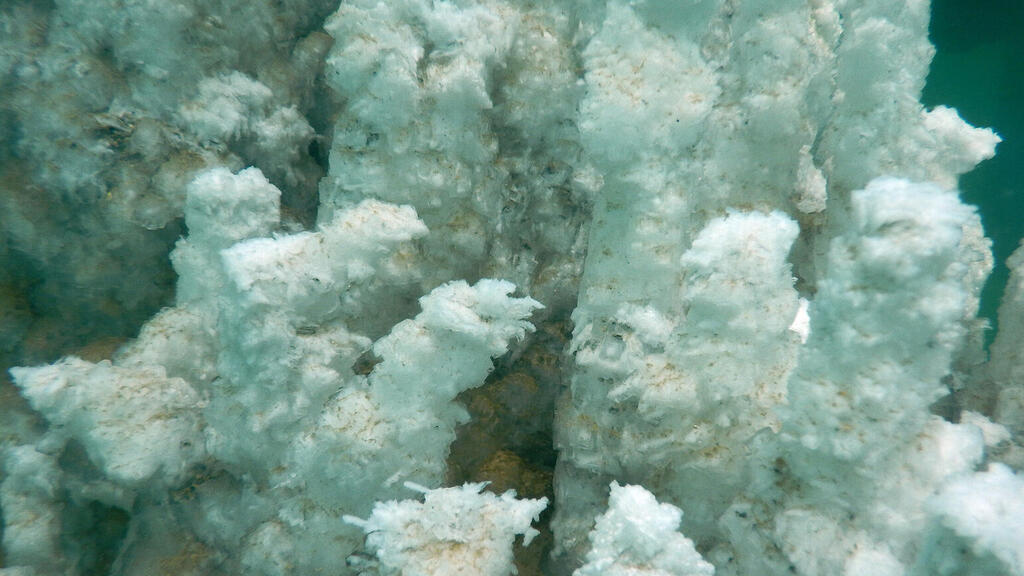

When the brine interacts with the Dead Sea’s waters, dissolved salts—mainly halite—crystallize, creating vents that can grow by several centimeters in a single day. Most of the vents observed were 1 to 2 meters tall, though some reached over 7 meters in height with diameters of 2 to 3 meters.

A new tool for predicting sinkholes

According to the researchers, these “white smokers” are particularly significant because they serve as early indicators of sinkhole formation. Sinkholes, which can reach widths of 100 meters and depths of 20 meters, have proliferated around the Dead Sea in recent decades.

The phenomenon is linked to karst processes, where layers of gypsum and limestone dissolve, accelerated by the erosion of subsurface salt deposits. This faster dissolution creates sinkholes—a hazard to lives, agriculture, and infrastructure.

“Until now, no one could predict where the next sinkhole might form,” Dr. Siebert said. His team demonstrated that these vents consistently appear where ground collapses occur as part of the sinkhole formation process.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

“This makes the white smokers an extraordinary predictive tool for identifying high-risk collapse areas,” Dr. Siebert noted, emphasizing that mapping and monitoring these vents is currently the most effective method for detecting zones vulnerable to imminent sinkhole formation.