Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The evolutionary history of early humans is a complex narrative, characterized by a diverse array of hominin species and adaptive processes that culminated in the emergence of Homo Sapiens.

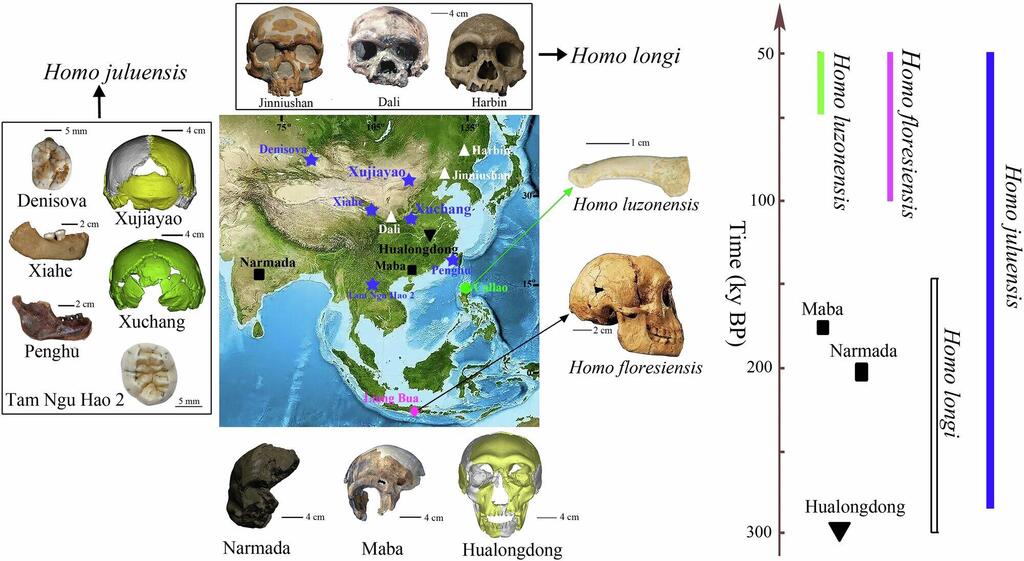

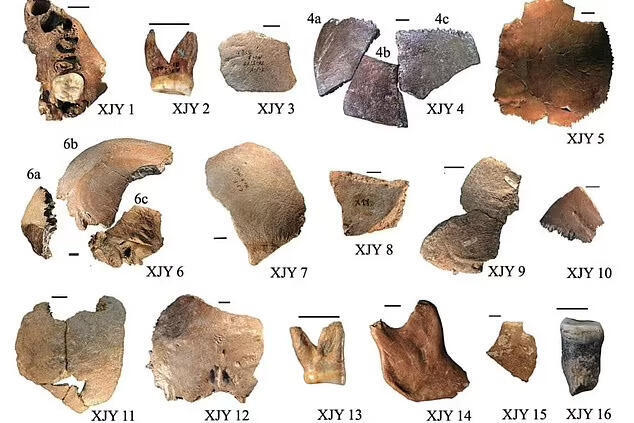

A groundbreaking new study analyzing the fossilized remains of 16 subjects—including cranial fragments, mandibles and teeth—has identified a previously unknown hominin species, Homo Juluensis. This species inhabited the forested regions of northeastern China approximately 300,000 years ago during the Middle Pleistocene.

Morphologically, it was notable for its robust cranial structures and unusually large dentition, which were significantly larger than those of Neanderthals or modern humans.

Korean anthropologist Prof. Christopher J. Bae from the University of Hawaii at Mānoa, a leading expert on Asian paleoanthropology with over three decades of field experience, spearheaded this research. Published in Nature Communications, the study contributes to resolving long-standing questions about the diversity and coexistence of hominin species in East Asia during the Late Pleistocene.

Ecological adaptations and extinction dynamics

Homo juluensis emerged around 300,000 years ago and demonstrated a range of ecological adaptations that highlight its capacity for survival in challenging environments. These hominins hunted wild horses in small, cooperative groups, manufactured lithic tools indicative of advanced technological capabilities, and processed animal hides to create clothing for insulation against the harsh winters. Despite these adaptations, the species eventually became extinct approximately 50,000 years ago, likely due to a combination of environmental pressures and demographic vulnerabilities.

"Life in northern China is not exactly easy; especially in winter, it gets very cold. They processed the hides of hunted animals with stone tools," Bae further hypothesized that the small, isolated social groups characteristic of this species may have contributed to their relative vulnerability, especially when compared to larger, more interconnected populations. Additionally, recurrent glacial cycles during this period, marked by exceptionally cold and arid climates, likely played a role in their population decline and eventual extinction.

Cranial and dental morphology

One of the most distinctive traits of Homo juluensis is its exceptionally large cranial capacity, estimated to range between 103 and 110 cubic inches—significantly larger than the average cranial capacity of modern humans (~73 cubic inches). However, Professor Bae cautions against equating this anatomical feature with superior cognitive abilities, noting that brain size alone is not a definitive measure of intelligence or adaptability.

The species’ large molars and robust mandibles have also drawn comparisons to the enigmatic Denisovans, a hominin group primarily identified through ancient DNA extracted from remains in Siberia, as well as limited fossil evidence from Tibet and Laos. Both Homo juluensis and Denisovans share the characteristic of hypertrophied molars and jaws, suggesting potential phylogenetic links between the two groups. Professor Bae, alongside his research collaborator Professor Shiyou-Ji Wu from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, posited that Homo juluensis may represent a regional adaptation within the broader Denisovan population or a closely related lineage.

Implications for human evolutionary models

According to Prof. Bae, the new fossil evidence from East Asia underscores the complexity of human evolution and highlights the need to reevaluate existing evolutionary models, adding that modern understanding of human ancestry must better align with the expanding fossil record, which continues to reveal unexpected diversity. He likened this process to organizing a family photo album, where some images remain blurry or difficult to identify. Together with Professor Wu, Bae has developed a more refined framework for classifying and interpreting ancient hominin fossils from East Asia, including specimens from China, South Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia.

A breakthrough in understanding morphological and genetic diversity

The discovery of Homo juluensis represents more than a mere addition to the hominin fossil record—it is a significant breakthrough that expands our understanding of the morphological and genetic diversity of Pleistocene-era hominins in Asia. With its unique anatomical features, survival strategies, and potential genetic links to other hominin groups, this species enriches the narrative of human evolution and provides invaluable data for future research.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

"This study clarifies a hominin fossil record that has tended to include anything that cannot easily be assigned to Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis or Homo sapiens,” Bae said. “Although we started this project several years ago, we did not expect being able to propose a new hominin species and then to be able to organize the hominin fossils from Asia into different groups. Ultimately, this should help with science communication."