Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

“I recovered from breast cancer eight years ago,” Israeli-American scientist, Prof. Regina Barzilay from MIT, tells us over a Zoom interview.

"When I was diagnosed, I felt cheated and deceived both by my body and by the system. I didn’t know I was at risk. There was no cancer in my family, no genetic mutations, no risk factors such as smoking. It was a genuine shock."

"I was also single and it was all very frightening. My situation was very precarious and I wasn’t getting decent answers – definitely not the kind of answers I’m used to as a computer science researcher. Sometimes, I wasn’t getting any answers at all. I had three mammograms and I was only diagnosed on the third," Barzilay says.

"In hindsight, you could see that the cancer was already present in the first test. I remember feeling such a sense of desperation. When I was fully recovered, I decided to move away from my research in natural language processing and dedicate the rest of my career to solving this problem. It makes no sense that we have such amazing artificial intelligence (AI) technology that helps us fly and buy, but when you really need it, it’s not there.”

She did exactly that. The world renowned professor built an AI algorithm called Mirai, which analyses mammogram x-rays and detects details in the x-ray pictures unseen to the naked eye that appear in the very early stages of the disease, before the tumor becomes cancerous.

Her system then provides statistic predictions gauging the woman’s risk level of developing cancer in the coming five years. The recently published results look very promising: the system which, has so far analyzed close to 130,000 mammograms, boasts a success rate twice that of the system presently used to assess mammograms.

Barzilay’s system is currently undergoing clinical trials in a number of countries, including in Israel in conjunction with Maccabi Healthcare Services and Assuta Hospital. It’s considered a gamechanger in predicting women’s risk of developing breast cancer in the future.

Testing frequency can therefore be adapted for each woman. This would not only improve detection and treatment of the disease, it would also serve to alleviate the workload of health services.

Unlike many other existing systems, Barzilay’s revolutionary system doesn’t find cancerous tumors: “What we’re doing is estimating the risk factor at a stage when there’s still nothing to see. Our system identifies double the types of cancers.”

This is just one way in which AI systems help battle the most widespread and lethal form of cancer among women. Out of Israel’s two and a quarter million Israeli women, about 5,000 are annually diagnosed with breast cancer – about one third of all new cancer diagnosis among women.

Most recent data records around 1,000 women dying of breast cancer annually. One in eight women is likely to have breast cancer at some time in her lifetime.

Public health awareness, mammograms and early-stage scanning, along with marked improvements in treatment methods over the past 30 years, have proved very successful. The percentage of women in Israel recovering from breast cancer is on the rise – in cases of early-stage detection, recovery rate has reached 90% and the percentage of women dying of the disease also is decreasing, albeit in small numbers.

Clearly, this still isn’t enough. The primary, essentially only, technology for detecting breast cancer tumors is the time-honored mammogram - an x-ray taken by pressing the breast between two panels and photographing the breast from various angles.

It’s unpleasant, but at least it’s quick. The mammogram has saved the lives of thousands of women. Fatalities have fallen by 30%, which is far from perfect. The mammogram is prone to errors. Dr. Shalom Strano, Unit Director at Shaarei Zedek Medica Center’s Breast Imaging Institute says: “37% of cases are missed. That’s very high.”

“Mammograms aren’t always precise. It very much depends on the person reading the x-ray. The test isn’t suitable for younger women or women with high density breast tissue, and it misses breast tissue changes that occur with age. This means that not only are we missing early-stage cancerous tumors, we’re also getting false positives, clogging up the health system," Strano says.

"Half a million women undergo mammogram tests every year. We only detect cancer in 5,000. We obviously welcome early detection, but this only applies to one percent of women. This means that 99% of tests are conducted 'for no good reason' and are congesting the health system. Some women are sent off for stressful and painful treatments, diverting resources from women who really do need the scans and making too many false positive diagnoses. Our greatest challenges are improving mammograms and increasing the detection precision.”

Prof. Barzilay tells us that the first problem she addressed was missing tumors in mammograms: “We were missing about one third of tumors when they were already cancerous. That’s what happened to me. The problem is that, like myself, most women who develop breast cancer hadn’t been classified as at-risk. Although we don’t feel we’re in danger, it’s clearly not always the case.”

Barzilay emphasizes, “We aim not only to detect the cancer in its early stages, but to see pictures without tumors and ascertain whether, and to what extent, the woman is likely to develop breast cancer in the future. These women can be then given the more accurate, less unpleasant, MRI test."

She adds: "There’s also medication that, if taken in time, can decelerate and even prevent cancerous tumors. If we know who is in danger of developing cancer, we can develop better medication designed for earlier stage detection, preventing hair loss and further undesirable treatment side effects.

“I also asked whether we were conducting too many scans. The problem is that while so many resources are allocated to standardized scanning at uniform regularity for the population at large, those actually at risk aren’t getting the resources they need. With the exception of women carrying the BCRA gene mutation, all women are presently given the same tests.

"I asked if the mammogram could provide me with a personal risk assessment. When should I come back for another test? In a year’s time? Two years’ time? Five? The present risk assessment uses an extremely outdated system for testing breast tissue density.”

“Mammogram technology is a thing of the past. It’s like putting lipstick on a corpse. It doesn’t solve the problem of early detection. At the moment, it’s the only widely-used technology and it looks like we’ll be using mammograms for some time to come.”

I’ve read that you say that you yourself don’t understand how the algorithm reaches its answers

“Yes. Do you fully understand your own microwave? Do you know exactly how your car works?”

No, but I didn’t write the algorithm

“I can explain the algorithm and how it creates data, but I couldn’t say how or why it produces its results. It’s like asking a calculator how exactly it multiplies 7,547 by 2,636 – it has different models and cognitive capabilities than you do. If anything, the question we should be asking is how to teach the machine to say that it doesn’t know the answer. As the machines improve, it’s harder for us to understand them – we don’t have those cognitive skills, like your dog smells things you don’t. That’s how I see the system’s cognition. You do what you can and then trust the system you’ve built.”

Great

“Also, the model we have now is terrible and I’d say close to random. Doctors make critical decisions based on insufficient information. Is our system perfect? No. Can it be improved? Definitely.”

Barzilay’s system is currently undergoing trials at eight locations all over the world, testing around 200 thousand women. The trials will only be completed in two years’ time, but the interim results are very promising.

Dr. Strano describes Barzilay’s system as “enormously innovative, a genuine breakthrough. She’s the first to assess risk from information embedded deep inside the pixels. Instead of wasting time questioning women about their height, weight and pregnancies, I look at my screen, I see a mammogram x-ray with a risk factor number. A woman may be at low-risk of developing cancer in the coming two years, high risk over the next ten years and so on."

She adds: "Barzilay’s calculations tell me when to call the woman in for her next test, what imaging methods to use etc. If we know the chances of problems arising in the future, it can greatly ease the strain on the health system. This is the future. It’ll very soon be on the market. I believe this is a greater breakthrough than early detection.

“The system can be everywhere within the year. Then health professionals just need to learn how to use it," he says.

“Within five years, mammography will undergo great changes worldwide. There’ll be more and more companies using early detection AI systems entering the market. Algorithms assessing risk will also be used more. The whole process will become much more efficient and the mammogram test will be used verification rather than detection. We’re no longer looking only at early detection, but rather at what tools to use for which women, and at what stage. The AI allows us not only to detect the cancer early on, but also to manage risks.”

“I think that within five years, 30% of women will be tested by MRI rather than mammogram. I’m very optimistic. It’s very hard to change the Health Ministry's directives, but the present detection indicators are outdated. In mammography, I’m considered very radical. Barzilay’s information is there and it can change the whole system. We mustn’t wait.”

Prof. Barzilay made Aliya, completed two degrees at the Ben-Gurion University in Be'er Sheva and continued onto post-doc research in the United States where she still lives. Her research focuses not only on early-stage detection, but it also deals with treatment.

“Amazing things have happened in the field in over the past six years. Everyone knows about the AI. There’s also been a change in molecular imaging and in the understanding of what each molecule can do. It’s transformed pharmaceutical production. We’ve already demonstrated that we can identify new antibiotics and develop new medication for different types of cancer. We’re now beginning to focus onto breast cancer. It’s definitely personal for me.

“The technology allows us to better understand how the current medication works. For example, like many other cancer survivors, I was given Tamoxifen, a very old and established medication, but it has multiple side effects. Macro data tells us that the medication helps, but did I personally benefit from it? Was it the right medication for me? We don’t know. It's been prescribed for years.”

What’s the difference between developing risk assessment tools and developing new medication?

“When we began with Mirai, we already had calculation tools. We weren’t starting out from nothing. When we started working on molecular imaging and developing personally tailored medication, there was almost nothing.

"Over the past five years, that’s almost all we’ve been doing – building algorithms to understand the molecular behavior. We need to develop a great deal of tools before we can create research that will allow us to confidently make fully informed decisions," she explains.

"That’s why we go for the most conservative solutions: research for developing medication takes over decade and in the meantime, we’re relying on outdated information. We must find a faster and more dynamic mechanism to understand whether the medication works. Once we understand this, we’ll be able to help many more women.”

What have you learned from your personal battle with cancer that you think can help other women?

“I remember the feeling of despair, the sense of fear and betrayal. I want to tell women that, looking at the statistics, for most women, it’ll be a very unpleasant year, but that you’ll emerge stronger. The treatments work and there’s light at the end of the tunnel. They’re not perfect but they’re improving. Survival rates are also very good. The most important thing is remaining hopeful.”

Barzilay is also developing blood tests designed to detect cancer that could replace the unpleasant breast cancer detecting procedure of biopsies and mammograms. We’ll come back to the blood tests later.

To understand and truly appreciate Barzilay’s breakthrough, we must look at the leading comparable initiative assessing personal risk: MyPeBS (My Personalized Breast Screening) is a large international research project funded by the EU, aiming to test 85,000 women worldwide.

The research is being conducted simultaneously in England, France, Belgium, Italy and Spain. Israel is partnering with the research project at Assuta Hospital and Maccabi Healthcare Services - who are surveying around 10 thousand women. To identify at-risk women, this research project also goes beyond blind surveying of the general female population.

The project (chaired in Israel by Dr. Michal Guindy) aims to examine whether using surveys, personalized to each woman’s risk level, would cost more than the standardized tests currently used, and whether it would be worth expanding the survey.

Mammogram testing every two years is presently included in Israel’s healthcare “basket” for women classified as at regular risk, aged 50-75 and for younger for at-risk women. “The decision as to when to conduct the mammogram relies on global data,” Dr. Guindy, Head of Ventures & Innovation, Director of Imaging Services says. “We’re striving to create an early detection test to give personalized recommendations to each patient.”

This large-scale project that will take a decade to complete divides women over 40 in two groups: Women in the first group are given mammogram tests in compliance with regular directives; Women in the second group have their specific risk factor of developing cancer in the next five years calculated based on personal details, such as age, family history, pregnancy history, breast tissue density, genetics, lifestyle etc. This process relies solely on x-rays and is longer and more complex than Barzilay’s system.

Guindy tells us: “The research is in its early stages, but we already have initial results showing that the current system is suitable only for one third of women: Another third is diagnosed as at low-risk and a further third is classified as at higher risk, recommending more regular testing. We can conclude that we need to categorize the general female population.”

This is where the AI that can quickly collate vast data, using more precise statistics and analyzing various population groups, comes in.

Dr. Strano calls this innovation “the bomb”. The plan is that it’ll eventually apply to other types of cancer: Imaging by personal risk – to better know the personal risk of breast cancer in each woman, and to utilize the correct form of imaging for her and the appropriate testing frequency. This will alleviate pressure from the health system and improve both earlier detection and treatment.

“It’s amazing when you think about it,” says Dr. Guindy.” We’ve been doing surveys for over twenty years and there are still so many unanswered questions about understanding cancer and its various factors. The only risk factor that correlates to breast cancer is the BCRA gene mutation – and even that’s a bit of a mess. We have conflicting trends and although the problem is as yet unresolved, we now understand much more. The problem is that we still don’t know how to get to young women with breast cancer. The survey only begins with 50-year-olds.”

Prof. Barzilay’s use of AI to battle cancer seems to be the most bright and promising, but it’s not the only one. We see AI in further fascinating research striving to replace or complement the old mammogram tests. Most of these tools are still in the clinical trial stages and are not widely used. Skepticism, however is gradually falling away as these advanced new tools are gradually coming into use.

While imaging currently uses x-rays, the much older technology of thermography is making a come-back: Thermography produces information based on the body’s blood flow and infra-red radiation emissions.

Any infectious activity in the body, cancerous or otherwise, creates a certain kind of discernable heat. The advantage of thermography is that no radiation is involved in the test, and it’s less unpleasant. In the past, thermography was considered problematic because of difficulties in reading and breaking down the body’s thermal map. But now we have AI with much more advanced processing and analysis capabilities.

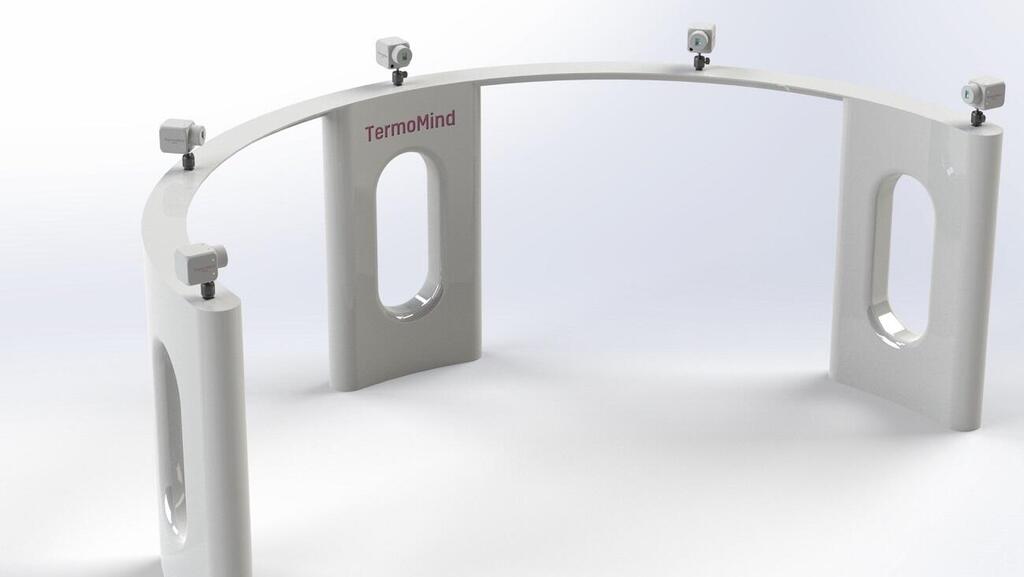

ThermoMind is a Haifa-based start-up that has developed thermal scanning technology to identify disturbances in blood cells caused by cancerous tumors. It also aims to replace mammograms. ThermoMind’s technology combines extremely sensitive infra-red cameras that can identify the tiniest temperature discrepancies and AI algorithms that analyze thermal patterns.

Najeeb Ayoub is ThermoMind CEO and Dr Larisa Adamyan is the company’s head of research. Adamayan is an ethnic Armenian Israeli with a background in Fintech and AI. She left Israel to study in Germany twelve years ago.

Ayoub is a cyber-security entrepreneur. They met during the COVID pandemic when their offices were located in the same building. Adamayan tells us that during the pandemic, they both felt a profound feeling that they wanted to make a meaningful contribution to society. “We decided look into healthcare what we could bring to the field of breast cancer that had potential.”

The pair chose breast cancer because of their own family histories. Adamayan’s mother and aunt and Ayoub’s mother and further family members had had breast cancer. “It was hard to watch my mother undergoing various treatments, going from one place to another, with all the side effects. I saw how it drained her of energy. It’s personal for us.”

Ayoub tells us: “I was devastated watching what happened within the family and at the hospitals.” .

During their research, the pair looked into thermography. “It’s not new,” Adamayan says. “It’s existed in research since the 1980’s, but it’s not in public use. There isn’t currently much confidence in thermography, but that’s because I the past the sensors weren’t sensitive enough, no AI tools were applied and there wasn’t any large-scale research.”

“We’ll be the first to do it,” Ayoub explains. “The difference is that in the past, the picture quality was terrible. The doctors themselves couldn’t analyze the pictures. They couldn’t identify the cancer or the activity of the cells creating movement and heat in the body. It’s a different story today. Our product has the world’s most sensitive sensor, combined with advanced AI.”

Ayoub shows me the sophisticated sensors.

Does breast cancer give off a special kind of heat?

Adamayan: “It’s a bit more complicated than that… several processes create heat in the body. There’s one specific pattern that’s caused by cancerous tumors, around which more blood cells develop. When you look at the blood mapping, there’s asymmetry in the blood."

"As the blood flow increases, the temperature goes up. Furthermore, the cancerous tumor is also hot and we can identify this temperature. It’s a multi-level approach only possible with AI. Our system can be used on patients from the age of 18. Because of the breast tissue density, mammograms can only be used on women aged 40 and above.”

Another advantage of thermography has over mammograms is that mammogram tests only finds lumps that have already formed. The blood system changes long before the cancer forms a lump and it can be caught earlier. Ayoub further claims that mammograms only recognize lumps 5mm and larger, while ThermoMind’s device can identify tumors from 2mm. “It can be done” he tells us confidently.

A year ago, the pair decided to return from Germany to found a company in Israel. To be precise, Ayoub returned and Adamayan simply came. They’ve been here for several months and they seem rather contented.

How is it to be back?

“Listen,” Ayoub says, “It’s amazing. I was a child when I left. To initiate something in Israel is ‘Wow’. I’d advise anyone to give it a try. It’s not easy. You don’t sleep much, but it’s all very exciting. I love it.

“Everyone here knows each other,” Adamayan says. “There’s a high degree of confidence between Israelis. It’s a great vibe of building something together.”

This is how ThermoMind’s imaging device works: The woman sits in front of the machine. There’s no contact, no pain and no radiation. The test takes about 15 minutes, most of which is spent cooling down the body to room temperature.

There’s presently only one machine, but 18 machines are to be manufactured in the coming month for research purposes. These machines will be sent to international locations in hospitals: The United States, Germany, France as well as to Sheba and Assuta hospitals in Israel. The trial is to include 30 women.

The duo presently live and develop their product in Haifa. “We started out in Tel Aviv,” Adamayan tells us, “But our manufacturers who create the sensors are based in the north of the country, so we came to Haifa and we’re very happy here.” ThermoMind’s thermal technology is based on military technology designed to detect enemies behind walls, which has been adapted and finetuned for precision purposes.

“That’s why we came back to Israel,” Ayoub explains. “SCD (Semiconductor Devices, a Rafel spin-off company), the world’s biggest sensor manufacturers, are here in Israel. Israel is a country of innovation. People move things here. It’s the best country for start-ups. There’s nowhere else like it.

“Our vision is to create new imaging standards – thermography." It can be used on various types of cancer, including skin cancer and cancer of the throat, diagnosing headaches and more. Almost everything that happens in the body - diseases, infections etc. - can be read in the blood: "At first it complemented mammograms, but “in the fullness of time,” Ayoub explains. “Our machine will replace the mammogram.”

It should be noted that a decade ago, Prof. Hadassa Degani of the Weizmann Institute developed a system to detect cancer by using temperature. She even got FDA approval, but her system was not adopted by the market.

Vayyar Imaging is another Israeli company emerging from military technology that’s interested in creating machines to circumvent (or at least complement) mammograms. Whereas ThermoMind works on heat, Vayyar works using motion sensors based on radio-waves.

The company was founded over a decade ago and its first product was a bra-like device which detected breast cancer. The company has since been active in creating further health related products including a product monitoring elderly people falling down.

Vayyar is also active in the vehicle market with a product reminiscent of Mobileye. In June of this year, the company raised $108 million at a valuation of over $1 billion - making it a unicorn.

The technology is based on a sensor based on radio waves (RF) which uses radio waves that bounce back from the body after hitting body tissue or other materials – but on the road or a child forgotten in the car.

The company was founded 11 years ago by Raviv Melamed, Naftali Chayat and Miri Ratner. The company founders declined to be interviewed for this article, but we emphasize that they are still very active in the field of breast cancer.

Also catching on in Israel are the efforts to detect cancer in its early stages not by imaging but by a simple blood test. This innovation has the potential to make biopsies redundant. There are numerous companies operating in the field: Senseera, headed by Prof. Nir Friedman was founded by researchers at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Their product detects a broad range of diseases using a simple blood test. By testing a single blood sample, Senseera’s method simply identifies dead cell fragments that drift into the blood from various skin tissues and understands where they came from and what disease or inflammation sent them into the bloodstream.

“Our analysis,” Prof. Friedman explains. “Lets us identify the source of the dead cells and the processes that led to them dying (cancer, infection processes, immune system problems, transplant rejection etc.) - thus preemptively detecting diseases.”

The company has now started clinical trials. I discussed the matter with Senseera CEO, Dr. Ronen Sadeh: “The advantage of our testing is that we don’t have to decide ahead of time what we’re looking for. We see everything and calculate what to report. Breast cancer is one of our targets and one of the goals in the coming year. We started a clinical trial with Assuta that will test for colorectal, breast, prostate and possibly lung cancer. Breast cancer, for some reason, is quite difficult to detect in the blood."

Why?

“We don’t know. It could be that something in the breast tissue won’t allow signals from the tumor and the dead cells to reach the blood. Perhaps the dead cells are out of the way and don’t reach the blood. We don’t know. We’re just getting started. Still, in studies we do see a signal in the blood in 30-50% of women who have breast cancer."

To overcome this problem, Senseera has come up with a crazy trick: “We’re pinning our hopes on not seeing the cancer early on, but rather seeing the immune system’s response to the cancer,” Dr. Sadeh tells us.

“The immune system tries to attack the tumor in its early stages. The immune cells activate genes that help them get to the tumor and fight it. This is easily visible in the blood. They don’t do this in the tumor’s later stages. So, there’s a window of opportunity when the body is fighting – that’s when we can find the cancer early.“

This system’s great advantage is that tests can be conducted using a simple blood test – much better than surveys and questionnaires. Although this also is being done by several further companies worldwide, Dr. Sadeh claims that Senseera’s technology is more advanced.

What’s your vision for the future?

“I don’t want to be optimistic. I think that in the future, blood tests will become more sophisticated and more accurate, so not all women be given mammograms, and definitely not biopsies. Rather they’ll be referred for blood tests, avoiding a great deal of suffering and discomfort while also taking pressure off health systems.

“Furthermore, our dream is to help breast cancer patients – not just to tell them they have cancer, but also predict how to treat it. Because the information we get from the blood is so rich, it can be classified for therapeutic purposes and contribute to creating personalized treatments. Our tests are precise, sensitive and cheap. We’ll be able to offer it for only a few hundred shekels.”

This is all just the tip of the iceberg. There are numerous further methods and there’s much more research on early cancer detection – as well as post-detection treatment, where they’re also doing crazy stuff:

Dr. Tali Ilovitsh at the Tel Aviv University has developed new, non-intrusive, technology that can destroy cancerous tumors using ultrasound energy on “explosive devices” sent to blow nano-bubbles on the tumor. It had only been experimented on mice, but it has recently announced that it also works on humans.

The Bnai Zion Medical Center in Haifa is using technology that freezes cancerous tumors using equipment developed by Israeli medical device company, IceCure Medical.

Even traditional treatment is improving: Prof Merav ben David who heads the Oncology Institute at Assuta Hospital, Ramat Hahayal tells us, “Thanks to state-of-the-art technology, instead of 25 radiations, we can now give some of our patients only five. Today larger doses can be given. The heart can be protected and breast injuries can be avoided. There are savings in terms of work-days and the woman can return to function fully."

Ben David also tells us of a further important development: “intraoperative radiation”. During the operation, a radiation device is inserted that destroys the tumor. She clarifies that this treatment is not suitable for all patients.

Dr Strano from Shaarei Zedek is optimistic not only regarding early detection but also in terms of treatment. “In the future, fewer women will find themselves on the operating table. Within a few years, surgery via the armpit will disappear. Oncology treatments will also improve and will be so successful that there’ll be no need for surgery. In a few years’ time, 30% of women with breast cancer won’t need surgery.”

“There are four main types of cancer. For two types, the treatment is so successful that 50% emerge fully recovered – so why operate? As treatments improve, there’ll be less and less surgery. Maybe patients could have a minor biopsy instead of surgery. It’s on its way. It’s just a matter of time.”

It's all too easy to get carried away with researchers’ and entrepreneurs’ the optimism. Prof, Ben David isn’t dismissing it. He’s just pouring a little cold water the flames of enthusiasm. She doesn’t see an end to the surgeon’s knife.

“To date, our approach hasn’t changed. Tumors have to come out. We currently have nothing to replace traditional treatment: surgery, complementary treatment, radiation, chemotherapy, biological and anti-hormonal treatment – in various combinations. It’s the only proven course of treatment. All the other things are all secondary. Mammograms, biopsies and radiation therapy aren’t going anywhere.”