Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Researchers from the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History have uncovered definitive evidence of cannibalism among evolutionary relatives of humans. A 1.45-million-year-old left tibia discovered in northern Kenya bears nine incision marks, suggesting that these early human relatives engaged in butchering and consumption of each other.

"The information we have tells us that hominins were likely eating other hominins at least 1.45 million years ago," said Briana Pobiner, National Museum of Natural History paleoanthropologist and research lead. "There are numerous other examples of species from the human evolutionary tree consuming each other for nutrition, but this fossil suggests that our species’ relatives were eating each other to survive further into the past than we recognized."

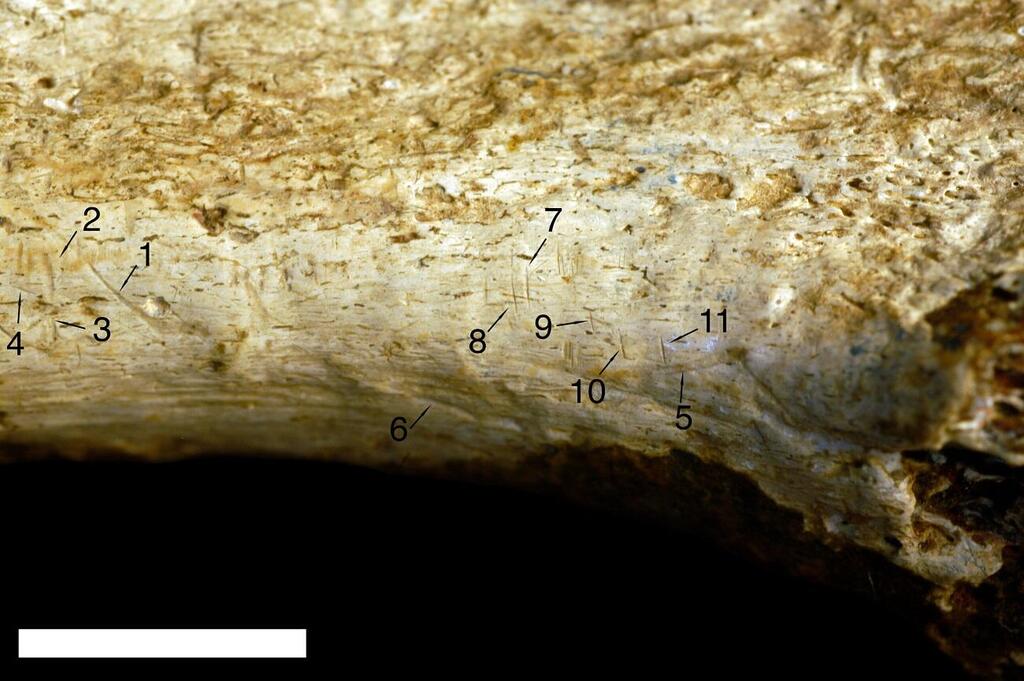

While conducting research on prehistoric predators and their interactions with ancient human relatives, Pobiner came across the fossilized shin bone (tibia) in the collections of Nairobi National Museum. Initially searching for bite marks, she discovered distinct evidence of butchery on the tibia, which immediately caught her attention. Through close examination with a handheld magnifying lens, she recognized clear indications of human-related activities.

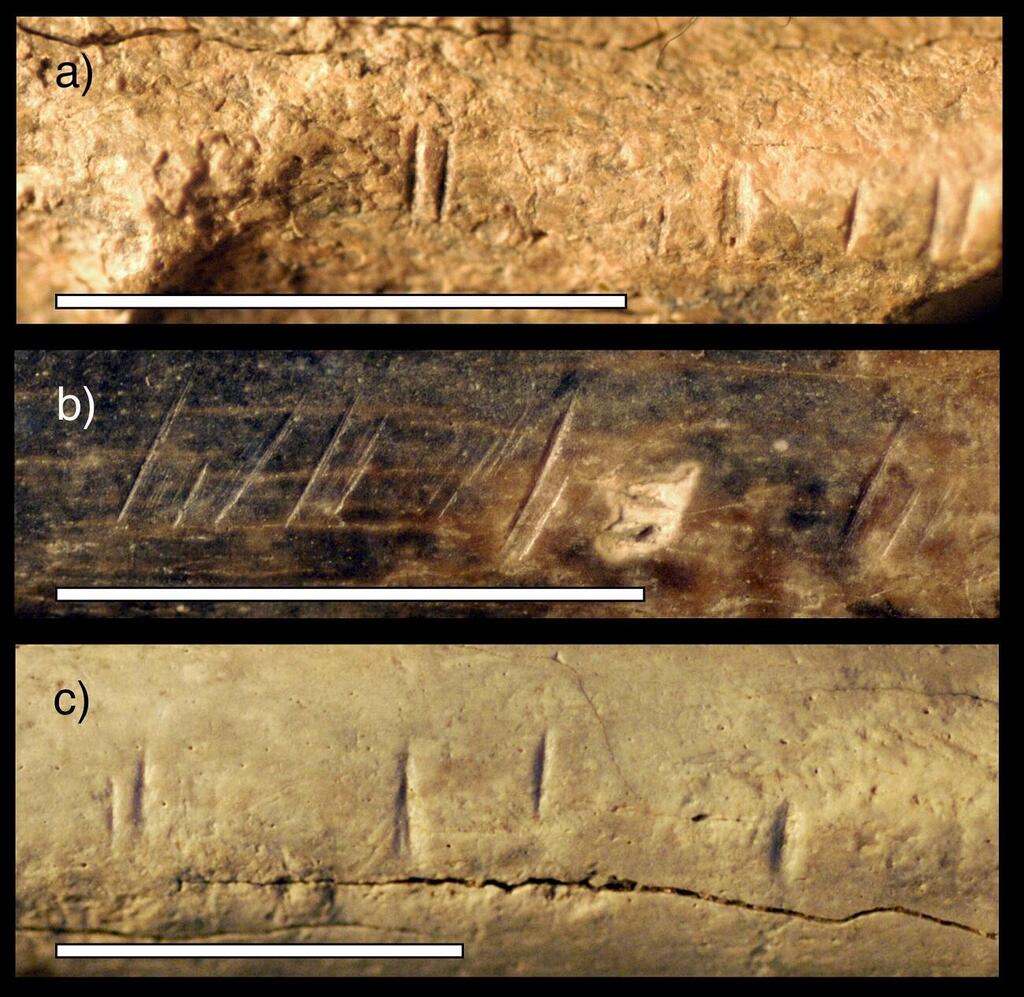

To confirm the nature of the observed marks on the fossil, Briana Pobiner collaborated with co-author Michael Pante from Colorado State University. Pobiner sent Pante molds of the cut marks without disclosing any information about their origin. Using the same material used by dentists for teeth impressions, Pante created 3D scans of the molds. He then compared the shape of the marks to a comprehensive database of 898 marks produced through controlled experiments involving teeth, butchery, and trampling. This rigorous analysis helped determine the origin and nature of the observed marks on the fossil.

Through thorough analysis, nine out of the 11 marks were conclusively identified as matching the characteristics of damage caused by stone tools. The remaining two marks were determined to be bite marks, possibly inflicted by a large feline predator, with a lion being the most likely candidate. Pobiner suggests that these bite marks could have originated from one of the three species of saber-tooth cats that inhabited the area during the time when the individual with this shin bone lived.

"These cut marks look very similar to what I’ve seen on animal fossils that were being processed for consumption," Pobiner said. "It seems most likely that the meat from this leg was eaten and that it was eaten for nutrition as opposed to for a ritual."

According to Pobiner, although this case might initially suggest cannibalism, there is insufficient evidence to definitively establish it since cannibalism involves individuals belonging to the same species acting as both consumers and consumed.

Initially classified as Australopithecus boisei and later as Homo erectus in 1990, the fossil shin bone's precise species remains uncertain due to limited information. Additionally, the presence of stone tool cut marks does not provide sufficient clues to determine the specific hominin species responsible for the cutting.

The absence of overlap between the stone-tool cut marks and the bite marks complicates the interpretation of events. It remains uncertain whether the sequence involved scavenging by a big cat after hominins consumed most of the meat, or if a big cat killed a hominin and was subsequently interrupted before other hominins took advantage of the situation.

A skull discovered in South Africa in 1976 has previously sparked discussions regarding the earliest evidence of human relatives engaging in cannibalistic behavior. The estimated age of this skull varies between 1.5 to 2.6 million years old, adding to the ongoing debate about early instances of intergroup violence among hominins.

To ascertain the validity of the fossil tibia as the oldest cut-marked hominin specimen, Pobiner expressed her desire to reevaluate the skull discovered in South Africa. This particular skull has been previously attributed with cut marks using similar techniques observed in the current study. By examining this skull again, it could provide further insight into the timeline of cut-marked hominin fossils.

"You can make some pretty amazing discoveries by going back into museum collections and taking a second look at fossils," Pobiner said. "Not everyone sees everything the first time around. It takes a community of scientists coming in with different questions and techniques to keep expanding our knowledge of the world."