Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Plastic has become a defining feature of our time. Its extensive use has resulted in us being surrounded by tons of plastic from all directions. It is highly durable and can take hundreds of years to decompose. It breaks down into tiny particles known as microplastics, which are found virtually everywhere and are imperceptible to the naked eye.

Related stories:

Plastic ingestion is an unfortunate reality among animals of all sizes, ranging from plankton to blue whales, and humans are no exception. Studies have linked plastic ingestion to adverse health effects, but the long-term effects remain unclear. Although laboratory studies have attempted to investigate this issue, the plastic particles used in these studies differ from those found in nature, and the impact on wildlife has yet to be fully assessed.

2 View gallery

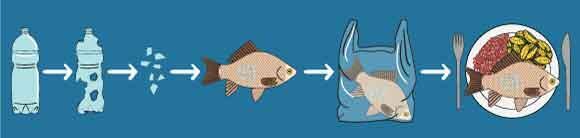

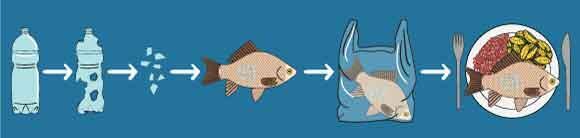

An illustration of plastic entering the body of a fish and eventually ending up on our plate

(Photo: Shutterstock, m.malinika)

In a recent study aimed at investigating the impact of plastic on wildlife, researchers examined the carcasses of flesh-footed shearwater (Ardenna carneipes) chicks that were approximately 90 days old on Lord Howe Island in Australia. At this age, the chicks are young birds that are capable of flight and have left the nest, but are still dependent on their parents for nutrition and survival. The researchers conducted a detailed examination of the glandular stomachs of the chicks to identify any signs of damage caused by plastic ingestion.

Cumulative damage caused by plastic ingestion

Sharp plastic pieces can cause injuries or punctures in the gut or stomach, leading to altered eating habits in animals and sometimes even starvation.

Tiny particles, such as nanoplastics, which are smaller than a micron, can be absorbed by the digestive system, enter the bloodstream, and accumulate in tissues and organs. These particles can cross cell membranes and even the blood-brain barrier. In mammals, they can potentially reach the placenta and affect the fetus in the womb.

In a recent study, researchers conducted post-mortem analyses and discovered scar tissue in the proventriculus, the first stomach out of two in birds, as well as extensive changes and destruction of tissue structure. The researchers measured the change by assessing collagen protein levels.

The body produces collagen fibers in response to the inflammatory process caused by plastic particle injuries, in order to build scar tissue and promote healing. Fibrosis, which is the accumulation of scar tissue, is a disease that impairs the organ's proper functioning, and when the inflammatory cause persists, it may become chronic.

The scientists conducted a comprehensive analysis of the contents of the shearwaters' stomachs, sorting, counting, and weighing the plastic fragments and pumice stones found within. Pumice stones are porous rocks that birds, including shearwaters, ingest in order to aid with the digestion of their food.

The findings revealed a significant correlation between the amount of plastic present in the shearwater's stomach and a decrease in the bird's weight, wing length, and an increase in stomach bloating and collagen content in its tissues.

However, no such correlation was found between the number of pumice stones and the degree of inflammation observed. As a result, the scientists proposed the term "plasticosis" to describe the development of fibrosis due to plastic ingestion.

Premature death

Studies tracking colonies of flesh-footed shearwaters have found that in recent years, the weight of fledglings has decreased, and many more have died before reaching maturity, likely due to the spread of plastic pollution.

When a bird’s stomach is scarred due to plastic ingestion, its function becomes impaired and it loses elasticity and volume. As a result, the bird’s body absorbs fewer proteins and other nutrients, making it more susceptible to infections and increasing the risk of anemia. This is particularly critical for fledglings who rely on their parents for food and the parents only feed them every few days before they fledge.

A scarred and diminished stomach holds less food, increasing the risk of the fledglings’ death before their parents return from foraging to feed them. Even if they manage to fledge, their condition may be compromised due to excessive plastic ingestion, and they may die shortly afterward.

In today’s world, exposure to plastic is inevitable, and we are just beginning to understand its immediate and long-term implications. According to projections, the amount of plastic waste in the oceans is expected to quadruple by 2050. Will wild birds be able to cope with the mounting plastic pollution, or will we be left with only rubber duckies in the bathtub?

Content distributed with permission from Davidson Institute of Science Education