Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

A nurse peeked out of the entrance to Ghana’s Mother and Child Hospital. She wore a muted green dress and a crisp white apron—like something from a 1920s film. The chipped yellow paint of the building behind her made the colors pop against her dark skin.

10 View gallery

A nurse peeks through the door at Ghana’s Mother and Child Hospital

(Photo: Maayan Hoffman/The Media Line)

Inside, patients waited to be seen. Rows of wooden benches lined the corridors, crowded with people—some slumped in exhaustion, others fast asleep. A few moaned as flies hopped between their legs. Outside, a donkey trudged down the dirt road. A yellow taxi with no doors followed, kicking up thick dust clouds that clung to the air—and to the people.

It was hot. Very hot. Upstairs, three Israeli volunteers worked through the stifling heat, their clothes soaked in sweat. They were trying to assemble an infant mechanical ventilator.

“We need the part today,” one told the hospital’s head, who phoned the biomedical engineer. The engineer promised to help—but moved slowly, uncertain whether he had the part or even knew what it was.

The room was nearly ready. A baby-sized bassinet stood beside a large oxygen tank. Inside it, a tan infant mannequin waited for the next day’s training.

10 View gallery

People sleep on the benches while they wait for service at Ghana’s Mother and Child Hospital

(Photo: Maayan Hoffman/The Media Line)

Kasoa, where the hospital is located, is one of the poorest regions in Ghana. People walk barefoot. Spoiled fruit is sold along the roadside. The hospital struggles to stay clean, let alone safe. Women give birth on rusted gurneys.

Still, babies are born, just like everywhere else. And about 10% of them struggle to breathe at birth. Their lives—or lifelong health—can depend on what happens in the first 60 seconds. That’s why the Israelis came.

After a 15-hour journey—five hours to Addis Ababa, five more waiting in the airport, and another flight to Ghana—a team from Neonatologists for Africa (NFA) arrived to help. Its mission: train midwives, nurses and doctors in modern neonatal resuscitation. To give newborns a better chance. To save lives, one breath at a time.

Why newborns die in Africa

Infant mortality rates in Africa remain alarmingly high compared to those in wealthier countries. In 2022, Sub-Saharan Africa recorded the highest neonatal mortality rate in the world: 27 deaths for every 1,000 live births, according to the World Health Organization. In contrast, Israel’s rate was 2.7; in the United States, it was 5.6.

The leading causes of death among children under 5 are infectious diseases and complications during the newborn stage, UNICEF reports. Around 79% of newborn deaths are linked to issues such as premature birth, trauma or lack of oxygen during delivery, birth defects and respiratory infections. According to the organization, nearly 80% of these deaths could be prevented with effective interventions and proper care.

In Ghana, the infant mortality rate is particularly high. A recent report from the Ghana Statistical Service estimated 59 deaths per 1,000 live births—more than double the Sub-Saharan African average.

“When a baby struggles to make the change from the life inside the womb to the outer life where he needs to breathe air, 10% of the babies do not make this transition smoothly, and they will face some kinds of challenges,” explained Dr. Meir Ezra Elia, founder of Neonatologists for Africa. “This could end in asphyxia either because the blood isn’t flowing or because there’s no oxygen. Asphyxia is when the brain cells do not get oxygen.”

According to Ezra Elia, proper ventilation is the key. “Once we solve the ventilation problem, the heart usually recovers on its own,” he said. “That’s why we focus on breathing first. In 90% of cases, everything else follows if you get that right.”

He added that even in developed countries, about 10% of newborns need help breathing immediately after birth.

A spark in Chad

Ezra Elia is a pediatrician who runs a Maccabi clinic in Tel Aviv. He’s also a certified Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) instructor. In 2022, he traveled to Chad with an Israeli Flying Aid medical delegation. What he saw there shocked him.

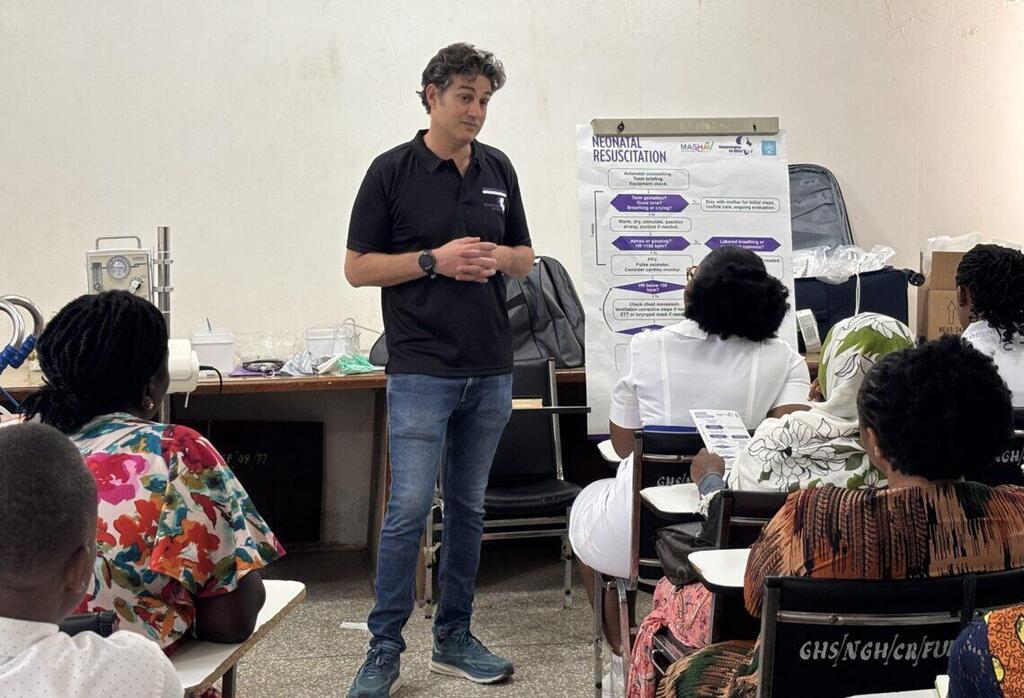

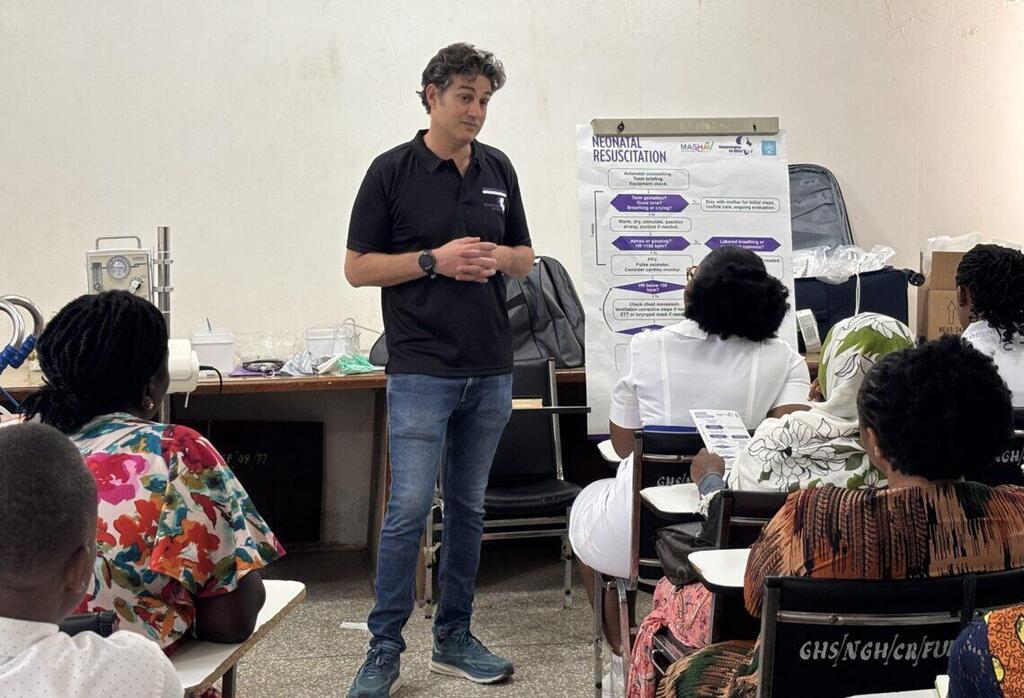

10 View gallery

Dr. Meir Ezra Elia, founder of Neonatologists for Africa, provides a NRP course for about two dozen local staff at Nsawam Government Hospital

(Photo: Maayan Hoffman/The Media Line)

When a newborn faced a respiratory complication and oxygen didn’t reach the brain, there was almost nothing the midwives or doctors could do. There were few working electrical outlets, no built-in oxygen or air supply, and—perhaps most troubling—a lack of knowledge and motivation to intervene.

“I went to the delivery room to see what was happening,” Ezra Elia recalled. “There was basically nothing. If an infant breathes, it breathes. If it doesn’t breathe, it doesn’t breathe. That was very frustrating.”

He called for the local bioengineer and asked, if he brought the necessary equipment, could it be connected? He snapped photos and took notes. The more he saw, the more convinced he became that real change was possible—with just a bit of effort and a modest investment.

Back in Israel, Ezra Elia decided to act. He posted on Twitter, hoping to raise $10,000 to purchase respiratory equipment and training tools. His goal: to return to Chad, install the machines and teach local staff how to use them.

The response was immediate. The campaign reached its goal in under an hour.

Soon after, Ezra Elia gathered a team of medical, operational and strategic professionals and officially established NFA. Charismatic and connected, Ezra Elia quickly built a strong and engaged board of directors. The organization now receives most of its funding through ImpactWell, JDC’s partnership with the Ruderman Family Foundation, to address last-mile health challenges through life-saving medical care among rural and underserved populations in Africa.

10 View gallery

A young Muslim woman awaits care outside of Nsawam Government Hospital

(Photo: Maayan Hoffman/The Media Line)

In 2023, Ezra Elia returned to Chad for NFA’s first mission. Since then, the team has completed missions in Ethiopia, Burundi, Malawi and Ghana.

“I saw this is relatively easy to solve—maybe not on the scale of a continent, but on the scale of a hospital,” Ezra Elia said. “Maybe not solve, but manage.”

Ezra Elia radiates energy and urgency—but always with a smile. It’s clear that even before founding NFA, he knew how to spot a need and seize the moment.

While in Ghana last month, he led an NRP course for about two dozen local staff at Nsawam Government Hospital in Nsawam. As he stood in front of the class, cracking jokes and engaging with the students, he told them, “This equipment is not very expensive, but it’s the top-of-the-art equipment. It’s the same equipment as in Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. The algorithm I am teaching you is the same algorithm they use. You have exactly the same knowledge. Now, the question is motivation.”

"A child born in Africa does not know he was born in Africa. His physiology is the same as the physiology of all babies around the world."

He reminded the group that babies born in Africa are no different from those born elsewhere.

“A child born in Africa does not know he was born in Africa,” he said. “His physiology is the same as the physiology of all babies around the world.”

Now, he told them, they have the tools and the training. The rest is up to them. The first minute of life—what he calls “the golden minute”—is the most important. It is the brief window in which a baby’s life can be saved or forever changed.

“We have one minute to intervene,” Ezra Elia told the class.

Tools and teamwork matter

The team brings two neonatal resuscitation devices to Africa: the Neopuff and the Neo-T. Both are sourced abroad and shipped in advance. The equipment is arranged by the team’s technical expert, Ezer Arava, a bioengineer who joins each mission to set up the machines. In the first few days, Arava moves between hospitals, classrooms and neonatal intensive care units to make sure everything is installed for training and functional for real-life use.

“In Israel, we have four lines in the hospital: air, oxygen, vacuum and the last one removes all the toxins,” Arava explained. “Here, they have nothing. In a few minutes, they are going to bring a cylinder of oxygen, and we will connect it to the machines with a flow meter and valve.”

10 View gallery

Dr. Meir Ezra Elia talks about the 'golden minute' at Nsawam Government Hospital

(Photo: Maayan Hoffman/The Media Line)

He explains that the machines blend oxygen with nitrogen and other gases to simulate room air. Natural air contains 21% oxygen, 78% nitrogen and traces of different gases.

“You want to give them natural air,” Arava said. “But you can change the blend to increase the oxygen if needed, slowly.”

The doctors on the trip—Dr. Michal Molad, a senior neonatologist at Carmel Medical Center; Dr. Adir Iofe, a physician at Bnai Zion Medical Center; and Ezra Elia—led medical instruction.

At the University of Ghana Medical Centre (UGMC), Molad conducted a day-long training session.

“Here comes the baby,” she said during the demonstration. “But he is not crying.” She then showed how to wipe the baby down, warm him up and gently massage him to stimulate breathing. Then, she suctioned fluid from his mouth and nose.

If the baby still wasn’t breathing, she placed a small mask over the baby’s mouth: “Finger on the valve for one breath, lift and count two-three, one breath, lift two-three.” She instructed the students to repeat the process until the baby’s chest visibly rose and fell.

“At this stage, most babies will start crying and moving,” she told them.

The students practiced using a brown-skinned infant mannequin, chosen intentionally after previous training sessions with white mannequins, which local staff felt less connected to.

10 View gallery

Dr. Adir Iofe prepares for training at Ghana’s Mother and Child Hospital

(Photo: Maayan Hoffman/The Media Line)

Occasionally, Molad jumped in to assist: “The baby is still not breathing?” she asked. She reminded them to check the mask seal, adjust the pressure, or increase the oxygen level.

“Still not breathing or crying? I go back. Is the mask properly sealed over the mouth? Maybe more pressure is needed. I add some, maybe increase the oxygen level. I do, and now the chest rises and falls, and the baby cries. The mask can be removed.”

She emphasized the importance of the “three Ps”: preparation, positioning and positive pressure ventilation (PPV).

“When the delivery happens and the baby needs help, I am not starting now to find where is the mask and where is the bed,” Molad said. “We want to be prepared.”

Next, she explained, the baby must be placed in the optimal position—flat, with no pillow—to support breathing. Then comes PPV: using the machines to deliver life-saving breaths.

UGMC is a modern facility in one of Ghana’s more affluent areas. But, an hour away at the Mother and Child Hospital, Dr. Iofe teaches the same class under very different conditions. Two hours farther, Ezra Elia runs the course in another packed, poverty-stricken classroom.

10 View gallery

Heaven David of Neonatologists for Africa shows the brown mannequin used by the team

(Photo: Maayan Hoffman/The Media Line)

Unlike the clean, air-conditioned classrooms at UGMC—equipped with state-of-the-art recording systems—the rooms at Mother and Child Hospital and Nsawam Government Hospital are small, outdated and stiflingly hot. The desks are worn and unstable.

The maternity wards have little running water. Faucets are attached to barrels filled for basic handwashing. The faux leather gurneys are rusted and barely mobile. The internet doesn’t work.

Despite the heat and harsh conditions, Ezra Elia’s students are attentive. Most wear the vibrant colors and bold patterns typical of the region. In jeans and T-shirts, the Israeli team looks slightly out of place in the Ghanaian heat.

A lasting impact

Dr. Richard M. Letsa of the Nsawam Government Hospital explained that many patients travel long distances for care. Most are farmers from rural areas.

The hospital handles between 350 and 550 births each month. According to Letsa, the leading cause of infant mortality is infectious disease, followed by complications from prematurity, and, of course, asphyxia.

“The training is going to make a big difference,” Letsa said. “We’ve been trying a lot of things to help reduce our mortality rate at this facility, and we think this will go a long way because when you have a good resuscitation station, you can increase survival and reduce the morbidity associated with the condition.”

He added that the hospital plans to compare its current data with data collected over the next six months once the new equipment is used regularly.

The students agreed. At the end of the training, Ezra Elia asked how they felt. One young woman in a large hijab beamed with gratitude. “I now know our babies are going to get the best of care. So we are grateful in Ghana. God bless you.”

Another young nurse praised Ezra Elia’s teaching style, calling it “relaxing and stress-free.” But what stood out most to her was how “practical” it was. “You took your time to really teach us, and no question was not relevant to you. You had the patience to explain everything to us, and then you made the lecture or the training so exciting.”

The volunteers’ view

But the work feeds the souls of the volunteers, too. Dror Schlafman, NFA’s accountant, joined the mission to help manage logistics. He is also a volunteer.

“It puts proportion on life,” he told The Media Line. “We’re coming from Israel, and with all the trouble we have there—the war and everything—it still puts everything in different proportion. You know your life is honey compared to what is going on here.”

“It is amazing to see that in such a relatively small effort, you can make such a huge difference."

What surprised him most, he said, was how much impact a small effort could make.

“It is amazing to see that in such a relatively small effort, you can make such a huge difference. … They wanted the equipment and the instruction, and they’re really, really into it,” Schlafman said.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

During lunch breaks, the students didn’t leave the room. Instead, they stayed behind to practice and ask more questions.

“I feel like I get even more than I am giving,” Schlafman said. “I think that my kids back home know that I’m going to Africa to help someone thousands of miles away from me—it’s the best education for my children.”

Challenges and culture

It also teaches patience. On the second day, one of the drivers’ cars broke down. He tried to keep driving, then walked a long way to fetch water and revive the engine. Finding a cab was nearly impossible, and the team stood waiting on the roadside.

10 View gallery

On the road in Ghana, where some people live in extreme poverty

(Photo: Maayan Hoffman/The Media Line)

The next day, heavy rains flooded the streets. After an already exhausting day, it took the group an extra hour to get back to the hotel.

Ezra Elia knows the missions won’t run like clockwork. “The culture is just different—slower,” he said. His goal isn’t to change that. What he hopes to do is influence how newborn care is approached and show that better outcomes are possible.

“I believe that if you build it, they will come,” Ezra Elia concluded. And now, they are.