Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

More than 50 years have passed since the discovery of a fossilized skeleton, estimated to be about 3 million years old, at an archaeological site in the Lower Awash Valley in the Afar Triangle of Ethiopia.

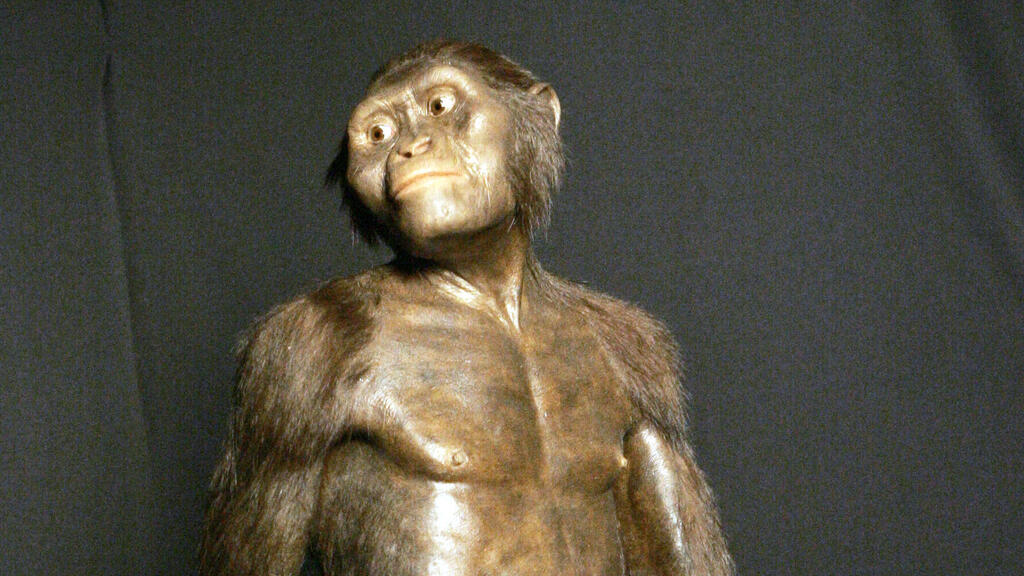

The research team that uncovered the remains on November 24, 1974, led by American paleoanthropologist Professor Donald Johanson, identified the specimen as a female of the species Australopithecus afarensis, one of the earliest species of the now-extinct hominin genus Australopithecus.

3 View gallery

Simulation of running performance of Lucy female Australopithecus afarensis

(Photo: Current Biology (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.11.025)

The discovery occurred while the iconic Beatles song Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds was playing in the background, prompting the team to name the fossil "Lucy." Now, more than 50 years after this groundbreaking discovery, a British-Dutch research team has conducted simulations showing that Lucy likely had the ability to run upright, although at a slower pace compared to modern humans.

Lucy's remains, found in East Africa, were revolutionary, as until that point, Australopithecus fossils had only been discovered in southern Africa. Lucy stood about 1.10 meters tall and weighed around 29 kilograms. Despite her small brain size, her leg bones were remarkably similar to those of modern humans, suggesting she and her species walked upright.

This upright posture required significant physiological adaptations in various body parts, from the toes to the pelvic bones that supported her body weight. Lucy became one of the most important specimens among early hominins, not only because of the preservation of her skeleton but also because her discovery provided strong evidence that modern humans evolved from less sophisticated ancestors.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

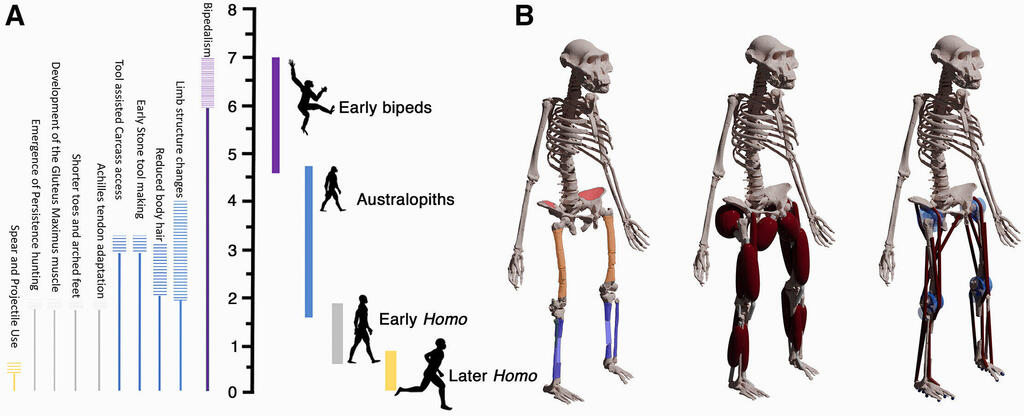

In a new study published in Current Biology, a team of muscle and skeletal experts, along with evolutionary biologists, explored whether Lucy was capable of running, in addition to walking on two legs and climbing trees. According to the researchers, evidence of running could shed light on the evolutionary process that enabled modern humans to become such efficient long- and short-distance runners.

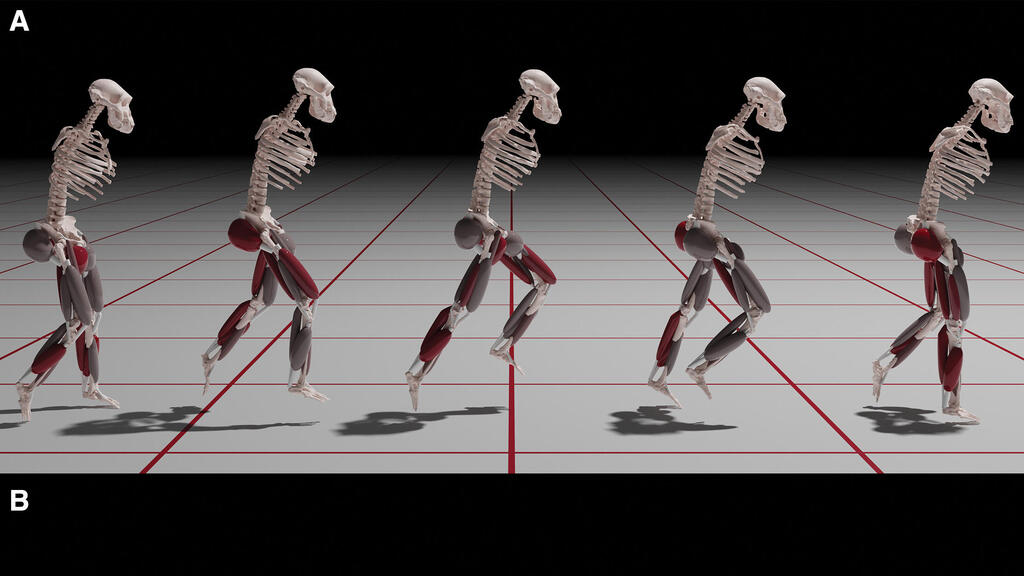

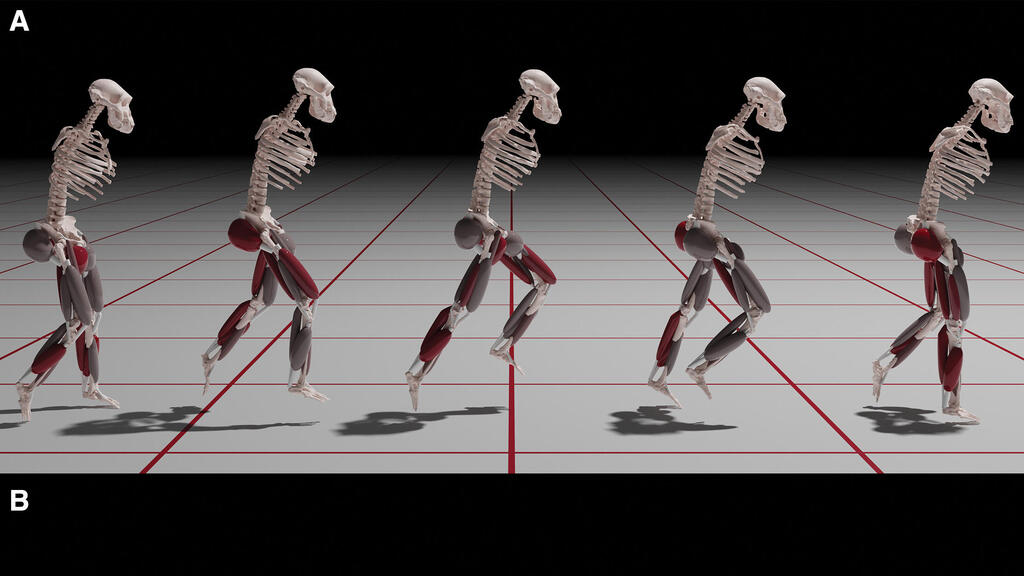

To assess whether Lucy could run upright, the researchers used a simulator developed over time for analyzing movement in both humans and animals. The results from the simulation indicated that Lucy could indeed run upright, despite lacking the Achilles tendon—a strong tendon located at the back of the lower leg, which enables flexion of the ankle joint and forward movement of the body while walking and running. The simulation also revealed that Lucy’s muscle fibers were shorter than those of modern humans, which previous research had shown are better suited for endurance running.

The simulation also showed that Lucy could not run as fast as modern humans, with a maximum running speed of only 5 meters per second. This means she would have completed a 100-meter sprint in at least 20 seconds. The researchers found that body size did not significantly affect Lucy's running speed compared to that of modern humans. They also examined Lucy's energy expenditure during running, discovering that it was taxing for her, suggesting that she likely only used her running ability in specific situations, not regularly.

The researchers concluded that the development of the Achilles tendon and muscle fibers in early humans likely enabled them to run longer distances as they evolved. Therefore, even after more than 50 years since Lucy’s discovery, she continues to provide valuable insights into human evolution.