Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The mission: Searching for life on Europa

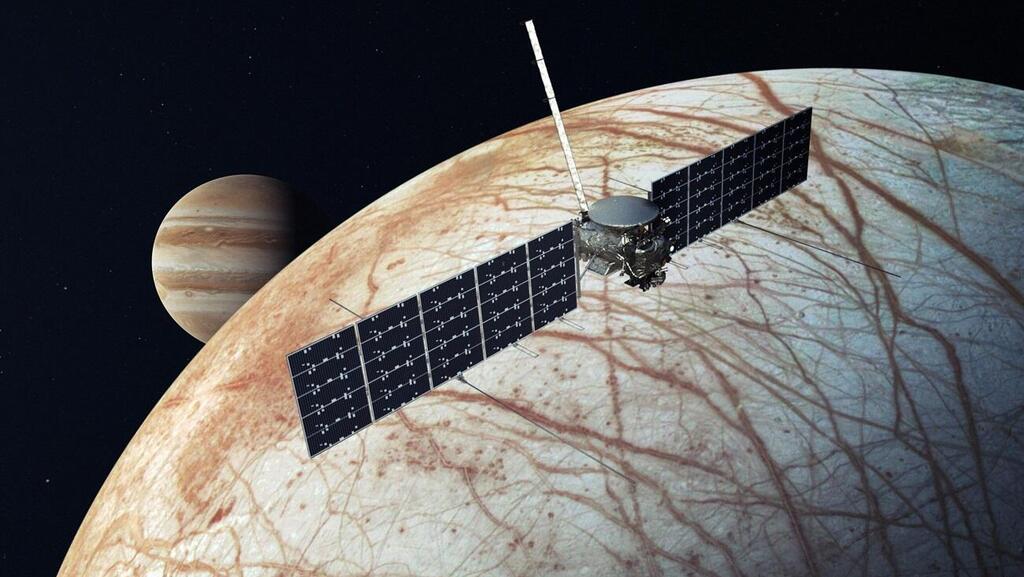

NASA, the United States Space Agency, successfully launched its Europa Clipper mission, an unmanned spacecraft aimed at studying Europa, one of Jupiter's largest moons. The mission's primary goal is to investigate whether conditions beneath Europa's frozen surface - where a liquid water ocean likely exists - could potentially support life.

Originally scheduled for launch on October 10, the mission was postponed due to Hurricane "Milton," which struck Florida. With the launch window for Jupiter open only until early November, NASA rescheduled the mission, and it successfully lifted off on October 14 from Kennedy Space Center.

The Europa Clipper is the largest spacecraft ever developed for planetary exploration. Without fuel, it has a dry mass exceeding 3,000 kilograms and is equipped with solar arrays spanning over 30 meters (~100 feet) when deployed – about the length of a basketball court – enabling it to generate enough power to operate even far from the Sun.

The spacecraft was launched aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket, marking only the 11th launch of the heavy-lift rocket since it began operating in 2018, which has maintained a 100% success rate thus far.

Similar to the European spacecraft JUICE, which was launched to Jupiter approximately a year and a half ago, the American spacecraft will embark on a long journey that leverages planetary gravity to conserve fuel. It is expected to perform a flyby of Mars in February 2025, pass within about 3,000 kilometers of Earth in December 2026, and then proceed to Jupiter, entering orbit around the planet in April 2030 after a five-and-a-half-year journey.

Once in orbit, its mission around Jupiter is expected to last at least four years, during which Europa Clipper will perform around 50 flybys of Europa, some as close as 25 kilometers from the moon's icy surface.

The Europa Clipper spacecraft is equipped with a suite of scientific instruments, including advanced cameras for detailed surface imaging, spectrometers to analyze chemical composition, ice-penetrating radar, and instruments to measure surface temperature, magnetic fields, and gravitational forces.

These instruments will help scientists confirm the presence of a liquid water ocean beneath Europa's icy crust, estimate the ice's thickness, and assess the potential for these waters to support life – probably not complex organisms like fish or mammals, but possibly bacteria, algae, or other simple life forms.

Planetary defense – a late follow-up

Last week, the European Space Agency (ESA) successfully launched the Hera mission – an unmanned spacecraft designed to assess the effectiveness of NASA's asteroid deflection experiment conducted two years ago. In that experiment, known as the DART mission, a spacecraft collided at high speed with the asteroid Dimorphos, which measures about 160 meters in diameter and orbits a slightly larger asteroid called Didymos.

Impact of DART spaceship with asteroid

(Video: NASA)

The collision, occurring at a velocity of approximately 22,000 km/h, ejected around 1,000 tons of soil and rocks into space, some the size of a bus, and created a crater 50 meters wide. Follow-up studies revealed that the impact shifted Dimorphos slightly off its course, shortening its orbit around Didymos by 33 minutes, from its original 12-hour orbit time.

The Hera mission was originally planned to run parallel to DART, with the European spacecraft documenting the collision up close and continuing to capture detailed images of the system to analyze the results. However, in 2016, ESA canceled the mission, only to decide three years later to proceed with it.

By then, it was too late to launch the spacecraft in real-time alongside DART. This week, Hera was launched aboard SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket and is expected to reach Dimorphos in about two years. “It would have been better to have the full characteristics, but we can live with that," said planetary scientist and Hera’s mission lead, Patrick Michel. "Fortunately, the outcome of the impact will [still] be there."

Hera is expected to enter orbit around both asteroids, then gradually reduce its distance to capture images of Dimorphos from as close as one kilometer. “This is the first rendezvous with a binary asteroid,” Michel added. “Hera is a detective, like Colombo. It’s going back to the crime scene and telling us what happened, and why.”

For its detective work, the spacecraft is equipped with visible light and infrared cameras, enabling it to transmit high-quality images of the system, particularly the collision site. Additionally, Hera will deploy two small satellites that will also orbit the asteroids.

4 View gallery

Detectives at the crime scene. The Hera spacecraft (left) with two small satellites around the asteroids Didymos and Dimorphos

(Illustration: ESA)

At the end of the mission, these satellites will attempt to land on Dimorphos to gather data on its surface composition and gravity. Hera itself is expected to orbit the system for about six months, after which scientists may attempt to land it on the larger asteroid, Didymos, to obtain further information about the entire system.

Bringing samples from Mars

NASA has added Rocket Lab to the list of companies awarded contracts for the preliminary development of a Mars sample return mission. The space agency announced that Rocket Lab will receive $625,000 to develop a sample collection mission at a significantly lower cost than the previously estimated $11 billion plan. The goal is to bring the samples back to Earth by 2040.

The Martian soil samples were collected by the Perseverance rover, which has been operating on the red planet for nearly four years. These samples are stored in sealed metal cylindrical containers, placed at various locations along the rover’s route.

Originally, NASA planned to collaborate with the European Space Agency (ESA) on a dedicated mission to retrieve the samples, but the project was canceled in April this year due to high costs. Subsequently, NASA announced it would invite private companies to submit alternative plans for sample collection. In June, NASA selected the first seven companies, including SpaceX, Lockheed Martin, Blue Origin, and Northrop Grumman. Each received up to $1.5 million to develop an initial proposal.

It is unclear why NASA decided to add another company to the contract or how Rocket Lab's current proposal differs from its original submission, which was not initially selected. So far, Rocket Lab and the other seven companies have provided little information about their planned missions, though SpaceX has indicated that it intends to use its Starship spacecraft for the mission.

The pandemic that cooled the moon

The lockdowns that accompanied the global COVID-19 pandemic, before vaccines were developed, led to significant changes in human activity patterns during that time.

Among other things, these changes resulted in a substantial reduction in carbon dioxide emissions, primarily due to decreased transportation, reduced air pollution, altered wildlife behavior, and even a decrease in background seismic noise. A new study has found that the effects of the lockdowns extended even further, causing a drop in the Moon’s surface temperature.

During the lunar day, the Moon's surface temperature is mainly influenced by the Sun and can reach up to 120 degrees Celsius near the equator at midday. With no atmosphere to retain heat, temperature fluctuations on the Moon's surface are extreme, dropping to about -130°C at night near the equator and even lower at the poles.

At night, the primary factor affecting the Moon's surface temperature is radiation reflected from Earth. Our planet is exposed to solar radiation, some of which is reflected directly into space by the atmosphere, while some reaches Earth's surface. A portion of this radiation is then reflected back into space.

4 View gallery

Changes in Earth's atmosphere affect the Moon's surface temperature. Illustration of the LRO satellite above the Moon, with Earth in the background

(Photo: NASA/GSFC)

The amount of reflected radiation depends on various factors, including atmospheric composition, cloud cover, and surface brightness. Many studies conducted during the pandemic indicated that the changes in human activity also led to a reduction in Earth's radiation emissions, particularly in April-May 2020, when many countries imposed lockdowns.

Researchers from the Physical Research Laboratory in Ahmedabad, India, examined changes in nighttime temperatures at six sites on the Moon’s surface. They used measurements from the radar of NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which tracks surface temperatures based on radiation reflection. Analyzing nighttime temperature data from early 2017 to early 2023, they found a drop of 8 to 10 degrees Celsius in the average temperature during April-May 2020 at all sites.

The average temperature across all six sites returned to pre-pandemic levels within a year and even increased afterward, suggesting a rise in air pollution and cloud cover on Earth. The researchers ruled out the possibility that the change was due to variations in solar activity during the studied period, as reflected in atmospheric radiation.

In their paper, the researchers note that the drop in lunar temperatures following Earth’s lockdowns not only highlights the close connection between the two worlds but also suggests that such measurements could be used to track global atmospheric changes on our planet through remote observation.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: