Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Team building in orbit

Space Pharma, an Israeli-founded company that develops microgravity laboratories for space-based research, has secured a substantial grant from the Horizon Europe program’s accelerator, part of the European Union, to produce cancer drugs in space.

The company, registered in Switzerland with a development center in Israel, has received a grant of over 2 million euros to advance its production system.

4 View gallery

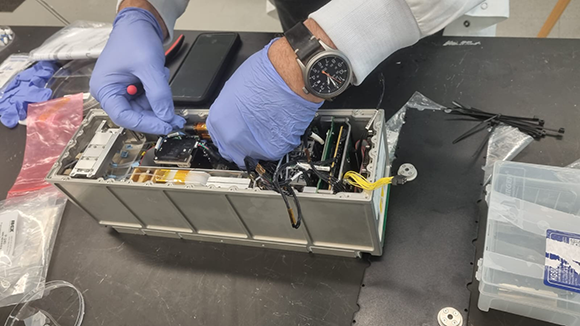

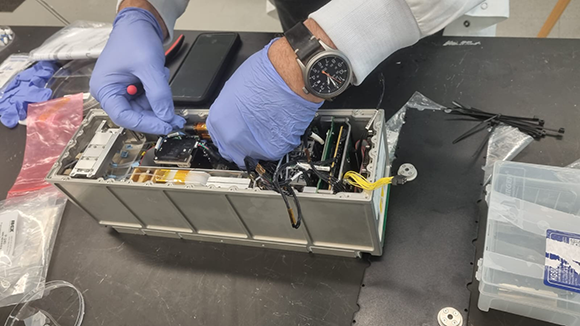

Space Pharma’s laboratories are compact devices, smaller than a shoebox. One of Space Pharma’s experimental systems undergoing final checks before its delivery for launch into space

(Photo: Space Pharma)

Additionally, the European Innovation Council (EIC) accelerator has committed to purchasing shares worth 7.5 million euros, contingent on Space Pharma raising an equal amount from investors. If successful, the company stands to secure a total funding of 15 million euros.

Space Pharma aims to produce two types of monoclonal antibodies—identical copies of a single antibody. One targets several types of tumors, while the other is specifically designed to treat skin cancer.

Partnering with a major pharmaceutical company, Space Pharma launches these antibodies aboard its microgravity labs to crystallize them into three-dimensional structures that cannot be achieved under Earth’s gravity.

“These crystals allow for administration of smaller doses of the drug, which are released gradually into the bloodstream, enabling subcutaneous injections instead of IV infusions and eliminating the need for hospital visits,” said Yossi Yamin, founder and CEO of Space Pharma Israel, in an interview with the Davidson Institute website.

“The crystals are very stable and do not require refrigeration or freezing, and are prepared as a liquid suspension before injection. All of this reduces manufacturing, storage, and transportation costs.”

The company has already conducted preliminary tests to produce a small quantity of crystalline antibodies in a lab launched to the International Space Station (ISS) earlier this year. Several hundred milligrams of antibody crystals were sent for quality, cleanliness and stability evaluations.

In the coming months, the company plans another experiment aboard the ISS, targeting to crystallize twice the previous yield. The substance will be tested on lab animals, assessed for human toxicity, and then move into clinical trials led by a pharmaceutical partner.

“We hope to receive FDA approval for the crystalline antibody formulation within approximately three years,” Yamin said. “Simultaneously, we are developing laboratory modules that will allow us to produce large quantities of crystals, yielding 8–12 kilograms of material per month during a space mission. That amount can translate into hundreds of thousands of doses, sold to consumers at over 100 euros per dose. We have recommendations from about twenty large pharma companies that have pledged to purchase the drugs once we can manufacture them.”

The company’s laboratories are small devices, smaller than a shoebox. They are equipped with miniaturized instruments customized for each experiment, ranging from spectrometers for monitoring the chemical composition, to microscopes that capture images of the processes, to sophisticated fluid pumping and mixing systems adapted to microgravity conditions. Fully computerized, the labs are remotely operated and monitored from Earth, while utilizing the ISS or another spacecraft for power and communication infrastructure.

The company is also advancing three additional projects in collaboration with major European pharmaceutical companies. One project involves creating three-dimensional tissues in microgravity for a company specializing in controlled-release drug implants. Another focuses on three-dimensional imaging of prion diseases, such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, which are caused by misfolded proteins in the brain. The third leverages the company’s expertise in miniaturization to enable rapid diagnosis of biopsies taken from patients in the operating room, enabling near real-time determination of whether a tumor is cancerous.

Space Pharma’s valuation is currently nearing $100 million, and the company is in the process of raising an additional $20 million. “Space Pharma has a strong R&D foundation and extensive experience in space projects that pave the way toward commercializing more R&D and drug manufacturing in space. This is a very reliable starting point,” noted the evaluators who approved the European grant. “[...] The approach Space Pharma offers leverages the advantages of space-based research and manufacturing in an accessible, automated, scalable and cost-efficient manner.”

The new life of the Mars helicopter

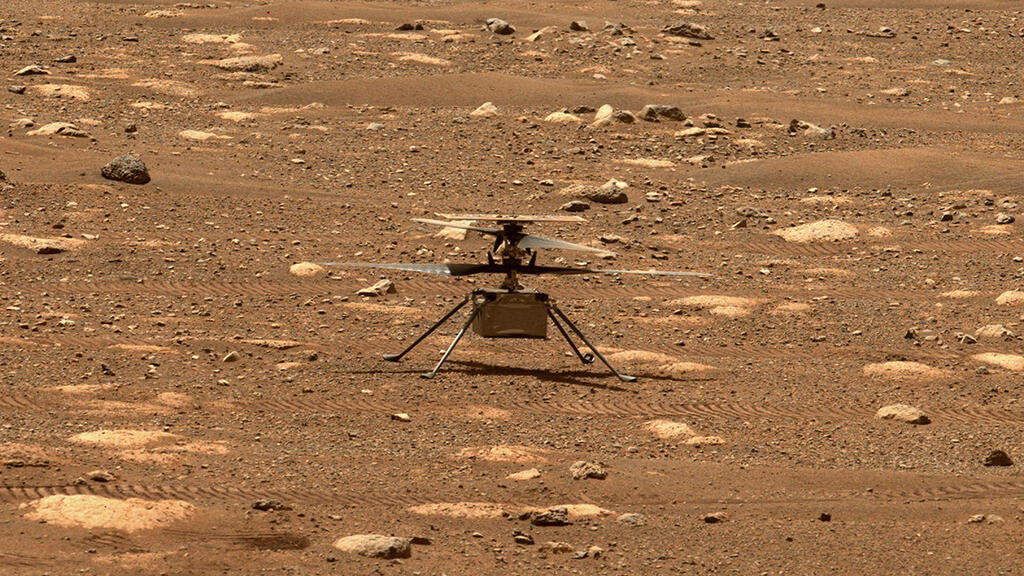

At the beginning of this year, NASA decommissioned Ingenuity, the first Mars helicopter, after one of its rotor blades was damaged. This pioneering aircraft, which worked alongside the Perseverance rover, far exceeded expectations, completing 72 flights over the Martian surface—well beyond its original goal of just five flights. In doing so, Ingenuity not only provided proof of concept for such flights in Mars' thin atmosphere but also demonstrated how these flights could be integrated into a broader mission.

However, about a year after its flights ended, its operators announced that Ingenuity’s mission is far from finished. It will continue to function as a sort of “weather station,” gathering daily environmental data, including a daily photograph of its surroundings. With sufficient memory to store data for up to twenty Earth years, according to the operators’ estimates, it is set to serve this new role for the long term.

This decision to repurpose Ingenuity came after the completion of an investigation into the circumstances surrounding its final crash landing, which damaged the blade. While the team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) could not determine the exact cause of the accident, they concluded that, aside from the damaged rotor blade, all other helicopter components, including its sensors, are intact and still operational.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

“We are very proud to report that, even after the hard landing in flight, 72 avionics battery sensors have all been functional, and she [Ingenuity] still has one final gift for us, which is that she's now going to continue on as a weather station of sorts, recording telemetry, taking images every single sol and storing them on board,” said Teddy Tzanetos, Ingenuity’s project manager at JPL, during a presentation at the 2024 Annual Meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU), which took place last week.

The only downside to this plan is that the grounded helicopter will have no effective means of transmitting most of the data it collects. The Perseverance rover—currently about three kilometers away—is already at the edge of the Ingenuity’s limited communication range. Ingenuity’s tiny radio transmitter was designed to operate efficiently over just a few hundred meters.

“I think it's a good bet that, within the next month, we'll lose contact forever,” said Tzanetos, “or until we come back in 20 years with astronauts, or until we turn back for sample return.”

At the same conference, JPL personnel also presented a preliminary design for the next-generation Mars helicopter, building on Ingenuity’s success. The future helicopter, which has no set mission timeline yet, will be larger than its predecessor and equipped with six rotors. It will be capable of carrying a payload of several kilograms, including scientific instruments capable of collecting valuable data during flight.

Cracks in the shield

After announcing earlier this month that the first crewed flight around the Moon will be delayed until 2026, and the crewed lunar landing until 2027, NASA reported this week that it has finally identified the cause of the extensive damage discovered in the Orion spacecraft’s heat shield during the Artemis 1 mission nearly two years ago.

4 View gallery

The Orion spacecraft’s heat shield from the Artemis 1 mission, shown after its removal for examination at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center

(Photo: NASA)

The Orion spacecraft, designed to carry astronauts to the Moon as part of the Artemis program, was launched on an uncrewed flight around the Moon. After a mission lasting over three weeks, Orion returned safely to Earth.

However, engineers inspecting the spacecraft post-flight discovered large cracks in its heat shield. Initially, NASA’s teams could not pinpoint the cause of the extensive damage, which was one of the factors contributing to the program’s crewed missions.

Orion’s ablative heat shield is designed to protect the spacecraft during atmospheric reentry. As the shield heats up, its outer layer disintegrates, and the detached particles carry away much of the heat generated by atmospheric friction during reentry—reaching temperatures over 1,000 degrees Celsius. This system, combined with additional insulation layers, prevents the spacecraft from overheating during its descent.

For the Artemis 1 mission, NASA employed a "skip" reentry method: the spacecraft entered the atmosphere at an angle that allowed lift to carry it back upward, toward space. Only upon the second re-entry did the spacecraft remain within the atmosphere. This method leverages atmospheric friction to slow the spacecraft but imposes greater demands on the heat shield.

A thorough investigation revealed that the cracks were caused by superheated gases trapped within the shield. Under normal circumstances, such gases escape through natural vents in the shield’s resin material. However, in certain areas, the shield lacked these natural escape points. As the gases expanded due to the extreme heat, they eventually forced their way out, causing the cracks.

“Our early Artemis flights are a test campaign, and the Artemis I test flight gave us an opportunity to check out our systems in the deep space environment before adding crew on future missions,” said NASA deputy associate administrator Amit Kshatriya. “The heat shield investigation helped ensure we fully understand the cause and nature of the issue, as well as the risk we are asking our crews to take when they venture to the Moon.”

Satellites against the wind

The powerful solar storms of the past year could have caused far more extensive damage, as they forced numerous satellites off their orbits. William Parker, a PhD candidate at the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), presented these findings at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

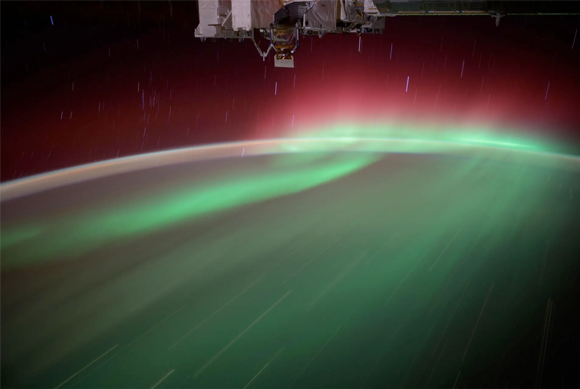

4 View gallery

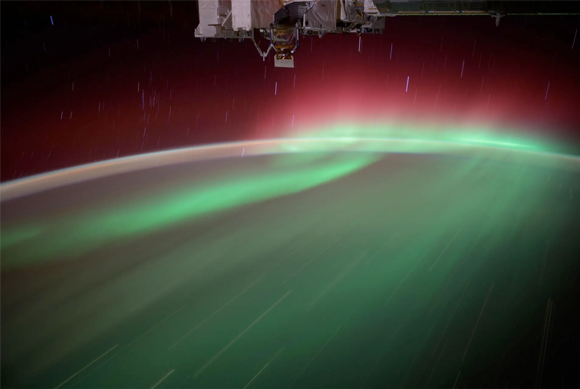

The aurora caused by heightened solar activity, as seen from the International Space Station

(Photo: NASA)

Parker analyzed satellite movement data and explained that after intense solar storms—such as the one in May— the particle density in low Earth orbit (LEO) increased by roughly tenfold. This resulted in significantly greater atmospheric drag, which affects satellite orbits, slowing them down, and pulling them closer to Earth.

According to Parker, following that storm, nearly 5,000 satellites had to perform orbit-raising maneuvers in a single day to correct their trajectories and return to their intended orbit - compared to an average of about 300 satellites performing similar adjustment maneuvers on an ordinary day. Almost all of these were Starlink satellites, part of SpaceX’s vast communications network.

“This is half of all active satellites deciding to maneuver at one time. This makes it the largest mass migration in history.” An even larger “migration” occurred after another powerful solar storm in October, following the launch of several hundred additional Starlink satellites between May and October.

This mass migration following solar storms significantly increases the risk of collisions between satellites. The danger is further compounded by satellite navigation errors caused by the storms. “As a result of this low skill in our forecasts, SpaceX saw 20 kilometers of position error in their one-day computations” of the orbits of Starlink satellites, Parker explained. “If we’re uncertain where our spacecraft are by 20 kilometers, then you can throw collision avoidance out the window.”

When many satellites are performing orbit correction maneuvers simultaneously—while some are uncertain of their exact positions—“then we have no idea when a collision is going to happen. We lose that capability for days at a time.”

Parker warned at the conference that many satellite operators are unaware of the severity of this risk. “Lots of operators continued to maneuver as if nothing was wrong, but all of those maneuvers were pointless because they didn’t represent reality,” he explained.

This situation, Parker emphasized, highlights the urgent need to improve space weather forecasting and better understand the impacts of solar storms. “This is critical infrastructure to all of our space operations moving forward, and it will only become more important as time goes on.”