The Nobel Prizes are awarded annually on December 10, marking the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death. Nobel, a Swedish industrialist who amassed a significant fortune primarily through the invention and development of explosives, later grew to regret the suffering and destruction his inventions had caused—or enabled. Toward the end of his life he resolved to dedicate his fortune to the benefit of humanity.

Upon his death in 1896, it was revealed that he had left most of his fortune to a fund, the interest from which was to be used to award prizes for outstanding discoveries and developments in five categories: three scientific - Medicine or Physiology, Physics, Chemistry - and two non-scientific - Literature and Peace.

Though Alfred Nobel had no direct descendants, his will was contested by distant relatives who received only minor bequests. After a protracted legal dispute, they were ultimately unsuccessful, and In 1901, five years after his death, the Nobel Prizes were awarded for the first time.

They quickly gained recognition as the most important and prestigious scientific awards in their respective fields. In 1969, the tradition was expanded with the introduction of the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel by the Swedish central bank, which became part of the ceremony and associated events, although not funded through Nobel's original endowment.

Over the years, the Nobel Prizes have faced significant criticism, some of it justified. A major point of contention is the exclusion of deserving scientists - particularly female scientists - who were overlooked for the prizes. Another criticism is the exclusion of organizations or institutions from most categories.

Only the Nobel Peace Prize allows for organizational recipients, whereas scientific prizes are restricted to individuals. This policy disregards the reality that many groundbreaking discoveries result from collaborations involving dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of researchers, as exemplified by large-scale international projects like CERN or LIGO.

Additionally, the prize committees have diverged from two stipulations in Nobel’s will: awarding the prize to a single individual per field and for work completed in the past year. Today, prizes are often shared by two or three laureates per field and recognize achievements that have stood the test of time, often decades, until their importance has been unequivocally proven.

The scope of scientific fields defined in Nobel’s will—Medicine or Physiology, Physics, and Chemistry—also presents challenges more than 120 years later. The absence of prizes for Mathematics or Computer Science is particularly notable, given the critical roles these disciplines now play—roles that Nobel likely could not have anticipated.

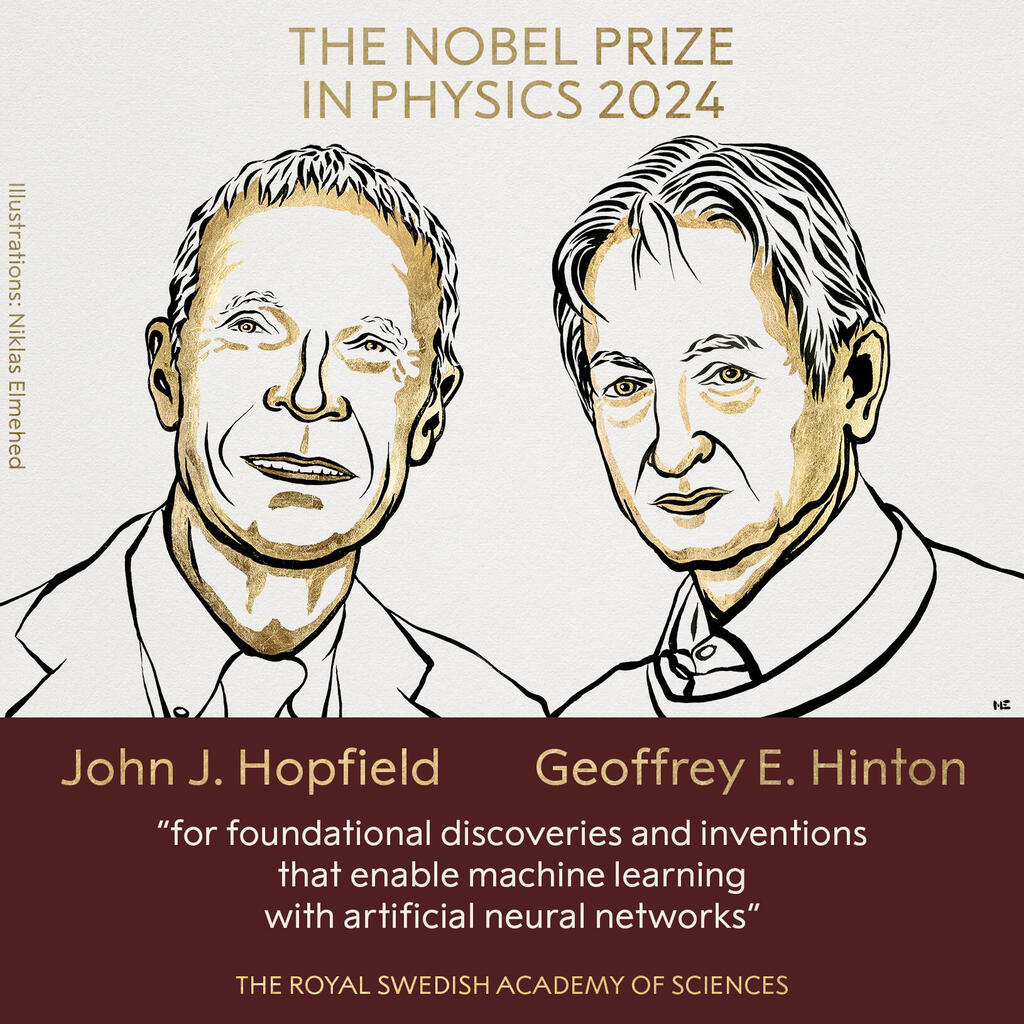

Occasionally, the prize committees have stretched the definitions to accommodate contemporary advancements, as they did this year by awarding the Physics Prize to two pioneers of artificial intelligence, even though the connection of their work to traditional physics is rather tenuous.

John Hopfield of Princeton University, USA, and Geoffrey Hinton of the University of Toronto, Canada, were recognized for their development of computational tools that simulate the activity of the nervous system, laying the foundational work for modern artificial intelligence.

The computer and the brain

The first modern computers, developed in the 1940s, were partially based on an abstract model of the human brain, where neurons represent logical gates, and their interconnected networks enable computational operations and memory storage.

In 1949, psychologist Donald O. Hebb proposed a theory that basic learning occurs by altering the strength of connections between neurons. According to Hebbian Theory, neuronal connections can be reshaped through experience. Specifically, when one neuron consistently activates another through electrical or chemical signals, the connection between them strengthens. Conversely, when neurons interact infrequently, their connections weaken.

These ideas spurred the development of artificial neural networks designed to emulate the brain's functions and learning mechanisms. In artificial neural networks, computer components simulate neurons, where nodes are assigned weights that represent the strength of connections. Adjustments to these weights in response to external stimuli enable the network to learn.

Such networks are adept at performing complex tasks, such as facial recognition, tumor diagnosis, and differentiating between Persian and Angora cats—tasks that are difficult to define through explicit programming. Unlike traditional software, artificial neural networks learn from examples rather than relying on predefined rules.

Early attempts to develop neural networks were largely unsuccessful, causing interest in the field to wane. However, breakthroughs in the 1980s led to a resurgence in research, resulting in significant progress.

John Hopfield, born in 1933, earned a Ph.D. in physics from Cornell University, worked at Bell Laboratories and later became a researcher at Princeton University. In 1980, he was appointed as a professor of chemistry and biology at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), where he sought to combine physics with biological systems and explore the development of computer-based neural networks.

Inspired by magnetic systems in which adjacent components influence each other, Hopfield developed an artificial neural network in which all neurons are interconnected, unlike traditional networks where layers of neurons are connected sequentially. Each connection between neurons was assigned a specific energy value, and the total energy of the system was calculated by summing all the connections.

In this network, called a "Hopfield Network," it is possible to input an image and then adjust the weights of the connections between neurons to achieve a minimum energy state. When a new image is input into the network, the values of the neurons are altered to reach a new minimum energy state, and so on.

This iterative process allows the network to "remember" and reproduce the original image or images it was trained to recall and retrieve information, images, or text based on similar details, akin to associative memory. The Hopfield Network, developed in 1982, was one of the first significant successes in the neural networks field.

Geoffrey Hinton developed an enhancement to Hopfield's network called the "Boltzmann Machine." Born in London in 1947, Hinton studied psychology and earned a Ph.D. in computing. However, he struggled to secure funding for neural network research in the UK, which led him to move to the United States and later to the University of Toronto in Canada.

Hinton applied statistical physics, particularly Boltzmann's distribution, which allows for the calculation of the probability of a specific molecule in a large system—such as a trillion gas molecules—having a certain velocity based on the system's volume, temperature, and pressure.

In 1986, Hinton introduced his artificial neural network, which allowed images to be input and consequently adjust the connection strengths between the "neurons." After sufficient iterations, the network reached a state where, even as certain connections strengthen or weaken, the overall properties of the machine, analogous to the general properties of a gas system, remained at equilibrium.

From this state, it could generate a new image, different from the ones it was trained on but in a similar style. The Boltzmann Machine is an early example of generative artificial intelligence. While inefficient and requiring long computation times, it laid the groundwork for modern image and text generation models.

Intelligence and proteins

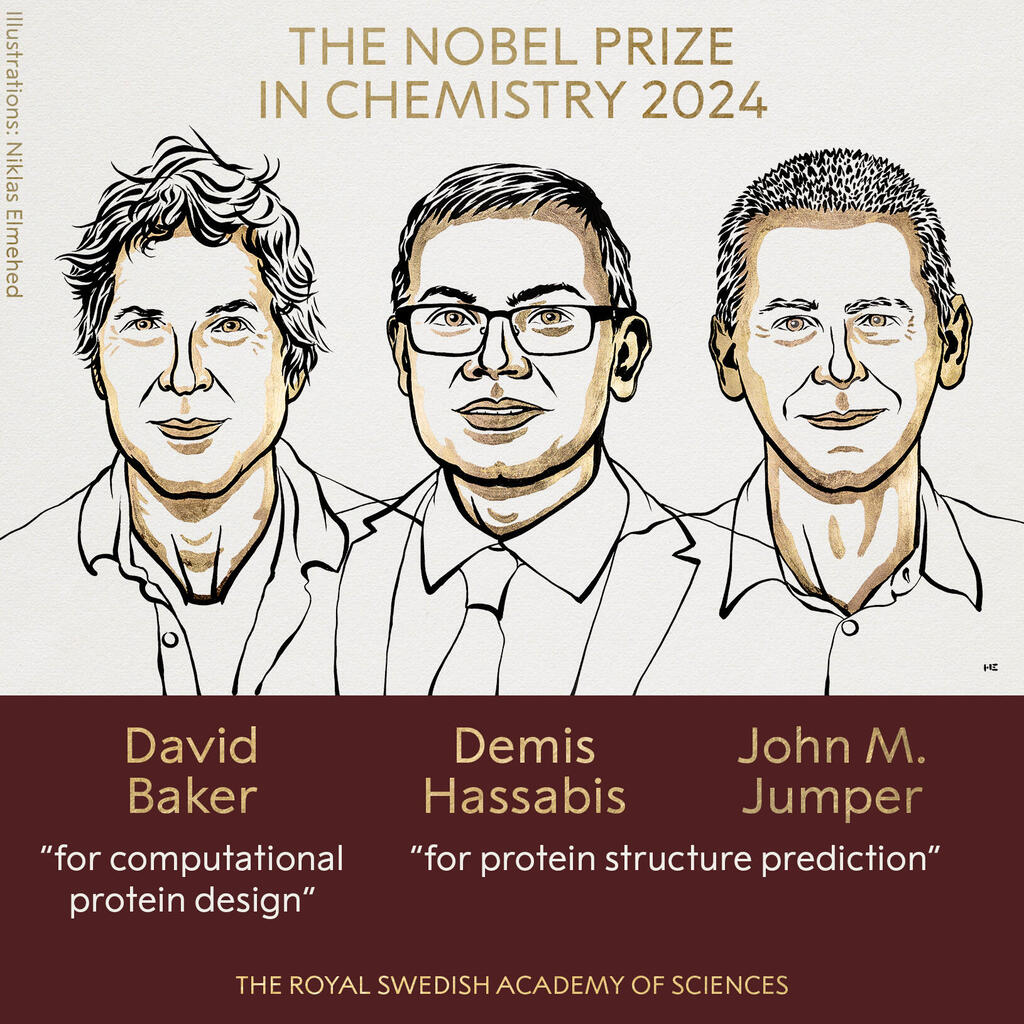

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics recognizes the application of physical principles to develop artificial neural networks, paving the way for the development of modern AI tools. Meanwhile the Nobel Prize in Chemistry this year celebrates researchers who have harnessed these technologies for scientific breakthroughs—specifically, deciphering the three-dimensional structure of proteins and designing artificial proteins.

Proteins are molecules composed of long chains of amino acids that fulfill a vast array of functions in living organisms. Our body’s cells are largely made up of proteins and also produce the proteins essential for life’s processes.

We could not breathe without the protein hemoglobin, which transports oxygen to cells; we could not eat without digestive enzymes, which are proteins that break down food; we could not defend ourselves against infections without antibodies, which are protein molecules; and we could not grow and reproduce without protein enzymes that replicate our genetic material.

The immense diversity of proteins in nature stems from different combinations of just 20 amino acids. Each protein is a long chain of hundreds or thousands of amino acids arranged in a specific sequence dictated by genes. After the amino acids are linked together like beads, the chain folds into a complex three-dimensional structure.

In this folded state, beads that were distant along the chain suddenly find themselves close together and must align in terms of electrical charge, solubility, spatial configuration, and more. The interactions between amino acids affect not only the structure but also the function of specific protein regions. Thus, the correct 3D structure is crucial for a protein’s function: misfolded proteins usually malfunction and are directed to recycling by the cell.

Understanding a protein’s three-dimensional structure is vital for science, medicine, industry, and other fields. For example, to develop a drug that neutralizes an enzyme, scientists must understand the enzyme’s structure and function to design a molecule that efficiently binds to it - or outcompetes it for binding with certain receptors.

Determining the three-dimensional structures of proteins is a complex task. In the past, the primary method was X-ray crystallography, which involves crystallizing the protein, exposing it to X-rays, and analyzing the diffraction pattern of the rays from the crystal with electron microscopy.

Determining the structure of a single protein using these methods often took years of work, sophisticated and expensive equipment, and a dose of luck - not all proteins could be readily crystallized.

Today, determining a protein's amino acid sequence is relatively straightforward. However, predicting its 3D structure from the sequence alone remains a significant challenge due to the vast number of possible sequence combinations and structural folds.

Over time, a competitive race has emerged among academic laboratories and commercial companies to develop methods for predicting a protein’s 3D structure, primarily through specialized software. In the 1990s, Google initiated a biannual competition to encourage teams to predict the 3D structures of proteins whose spatial structures had not yet been deciphered.

Experimental methods were used in parallel to determine the actual structures of the proteins, allowing comparisons between the software predictions and actual structures. Early software achieved only about 40% accuracy, but by the late 2010s, a new private contender transformed the field.

DeepMind’s AlphaFold first entered the competition in 2018, achieving 60% accuracy. By 2020, it had already reached over 90 percent accuracy! Founded in 2010 by Demis Hassabis (b. 1976), a British computer scientist with a PhD in neuroscience, DeepMind originally aimed to develop AI for complex games like chess.

However, it later pivoted into protein structure prediction, thanks in part to John Jumper (b. 1985), a computer scientist with a PhD in theoretical chemistry, who joined DeepMind to lead the AlphaFold team.

AlphaFold leverages the vast repository of protein structures accumulated over nearly a century, using it to predict how a given protein folds into its 3D shape. In its first stage, AlphaFold’s algorithm compares the target protein’s sequence to those of other proteins.

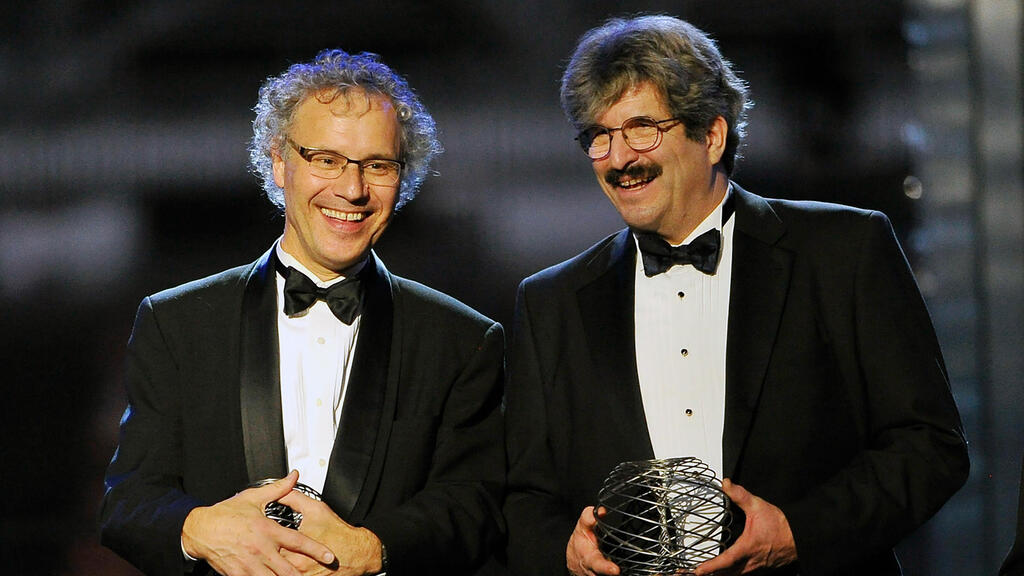

10 View gallery

Nobel Prize laureates Demis Hassabis and John Jumper

(Photo: TT News Agency/Christine Olsson, Reuters)

It then analyzes additional parameters, such as conserved regions in the sequence that have remained unchanged throughout evolution and thus exist in other similar proteins. This information helps assemble a 2D representation of the protein, which is then compared by the software against a database of over 180,000 known protein structures. Through iterative refinement, AlphaFold achieves remarkable accuracy.

For this groundbreaking development, which propelled protein structure prediction forward, Hassabis and Jumper share half of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

The other half of the prize is awarded to David Baker of the University of Washington. Born in 1962, Baker developed in the 1990s an early software program called Rosetta for the prediction of protein structures.

He and his colleagues later realized that the software could also be adapted for the reverse process: starting with a desired 3D protein structure and determining the amino acid sequence needed to produce it. In 2003, this approach enabled the successful prediction of the structure of a de-novo designed protein.

The next step involved producing the artificial protein and using crystallographic measurements to confirm that its structure matched the one originally specified in the software.

This breakthrough gave rise to a new research field of artificial protein design. It allows for the creation of entirely novel proteins with predefined properties, such as proteins that bind to opioid molecules, molecular motor proteins, vaccine-related proteins, or specialized enzymes that synthesize new molecules.

Following AlphaFold’s success, Baker recognized AI’s transformative potential and integrated a similar model into Rosetta, significantly enhancing its ability to design new proteins. In 2008, Baker was awarded the The Raymond and Beverly Sackler International Prize in the Physical Sciences by Tel Aviv University for his contributions to the field.

A small molecule with a big impact

The Nobel Prize in Medicine is the only scientific Nobel this year that is not related to artificial intelligence, but it is closely tied to protein production. It has been awarded to Gary Ruvkun and Victor Ambros for the discovery of microRNA and its role in regulating gene expression.

Proteins, as mentioned earlier, consist of sequences of amino acids. How does the ribosome—the machinery that assembles proteins, know the correct sequence? According to the DNA sequence in the cell nucleus.

Much of our genetic material consists of instructions for protein production. When a cell needs to produce a specific protein, it creates a "working copy" of the DNA from a similar material, RNA. This copy, called messenger RNA, or mRNA, exits the cell nucleus, binds to the ribosome, and serves as a template for protein synthesis.

Almost every cell in the body contains a complete copy of our DNA, which includes instructions for building all proteins. However, not every cell produces all proteins. In a muscle cell, proteins that make up contractile fibers are produced; in the retina of the eye—proteins that change shape in response to light; in nerve cells, proteins that enable the transmission of electrical signals are produced, and so on in the many different cell types in our bodies.

How does a cell "know" it needs to be a muscle cell, for example, and produce the corresponding proteins? Ambros and Ruvkun uncovered one mechanism ensuring that each cell produces only the proteins it needs.

As early as the 1960s, researchers discovered that there are special proteins capable of regulating the extent of production of other proteins in a particular cell.

These proteins were called transcription factors because they bind to specific locations on the DNA and influence the likelihood that a particular gene will be transcribed into messenger RNA, ultimately driving the cell to produce the corresponding protein. For many years, transcription factors were believed to be the primary regulators of protein production in cells.

In the late 1980s, Ambros and Ruvkun were both conducting postdoctoral research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the lab of Robert Horvitz, who would later receive a Nobel Prize in Medicine. Ruvkun, born in California in 1952, arrived there after completing a PhD at Harvard University, while Ambros, born in 1953 in New Hampshire, stayed at MIT after completing his PhD there in 1979.

They studied embryonic development and searched for genes specialized in producing new types of cells. Their research was conducted in the tiny roundworm C. elegans, a model organism widely used in genetics studies. Each focused on a different gene influencing developmental timing in the worm.

Ultimately, they discovered that the two genes, lin-4 and lin-14, produce complementary RNA molecules that can bind to each other. This binding prevents the ribosome from reading lin-14 RNA and producing its protein, and may also accelerate the degradation of the lin-14 mRNA.

This discovery revealed a new type of RNA—microRNA. Unlike mRNA molecules, microRNAs do not carry instructions for producing proteins. Instead, they regulate the production of other proteins. Unlike protein transcription factors, microRNAs act after the mRNA of other genes has already been produced, preventing the production of the protein that would have been synthesized based on this mRNA sequence.

This allows the cell to respond quickly when needed, stopping protein production even after the mRNA has already been transcribed. For example, if body temperature rises, cells may produce proteins that protect DNA from heat damage. However, when the temperature drops, they must rapidly halt production to conserve resources.

Ambros and Ruvkun published their findings in two landmark scientific papers in 1993, but many initially believed this mechanism was unique to C. elegans, in which it was first discovered. However, in 2000, Ruvkun and colleagues discovered another microRNA, let-7, present in the genomes of many animals.

This hinted at the widespread nature of microRNA. Within a few years, hundreds of microRNA genes were identified. It is now known that this mechanism is present in all multicellular organisms, not only animals but also plants and fungi, and it appears to be essential for their development.

The study of micro-RNA has taught us much about the regulation of protein production in cells and allows us to investigate what happens when this mechanism malfunctions. Abnormal microRNAs expression can lead to various diseases, including cancer, problems with skeletal structure and various organs, and more.

If a deficiency or excess of microRNAs can cause diseases, it may be possible to develop treatments based on these small molecules.

Among the many awards they have received, Ruvkun and Ambros were awarded the 2014 Wolf Prize, alongside former Israeli researcher Nahum Sonenberg. Three years earlier, Ruvkun also received the Dan David Prize, awarded at the Tel Aviv University, alongside biologist Cynthia Kenyon.

Unfortunately, it should be noted that this year there were no women among the science laureates, breaking a two-year streak of female representation in these prestigious awards.

Disparities and traumas

The Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for 2024 has been awarded to three researchers from the United States: Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson - for a series of studies that examined the causes of economic disparities between nations and highlighted the critical role of social institutions in fostering national economic prosperity.

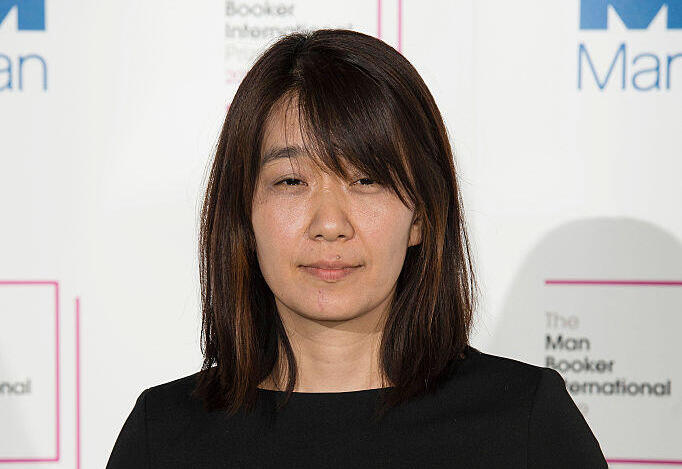

The 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature has been awarded to South Korean author and poet Han Kang. She has published 13 works of prose and poetry, addressing themes of personal and national crises and traumas.

Her works include The Vegetarian, which explores the life of a dutiful wife who decides to stop eating meat and even cooking it for her husband. The prize committee noted that Han, born in 1970, receives the award “for her intense poetic prose that confronts historical traumas and exposes the fragility of human life.”

The Nobel Peace Prize this year is also related to coping with traumas and has been awarded to the Japanese organization Nihon Hidankyo, the Japanese abbreviation for its full name, "The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations."

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

Established in 1956, Nihon Hidankyō represents survivors of the atomic bombings of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, which marked the end of World War II. It also unites victims of U.S. nuclear testing in the Bikini Atoll, during the 1950s.

The prize committee announced that the organization “is receiving the Nobel Peace Prize for 2024 for its efforts to achieve a world free of nuclear weapons and for demonstrating through witness testimony that nuclear weapons must never be used again.”