Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

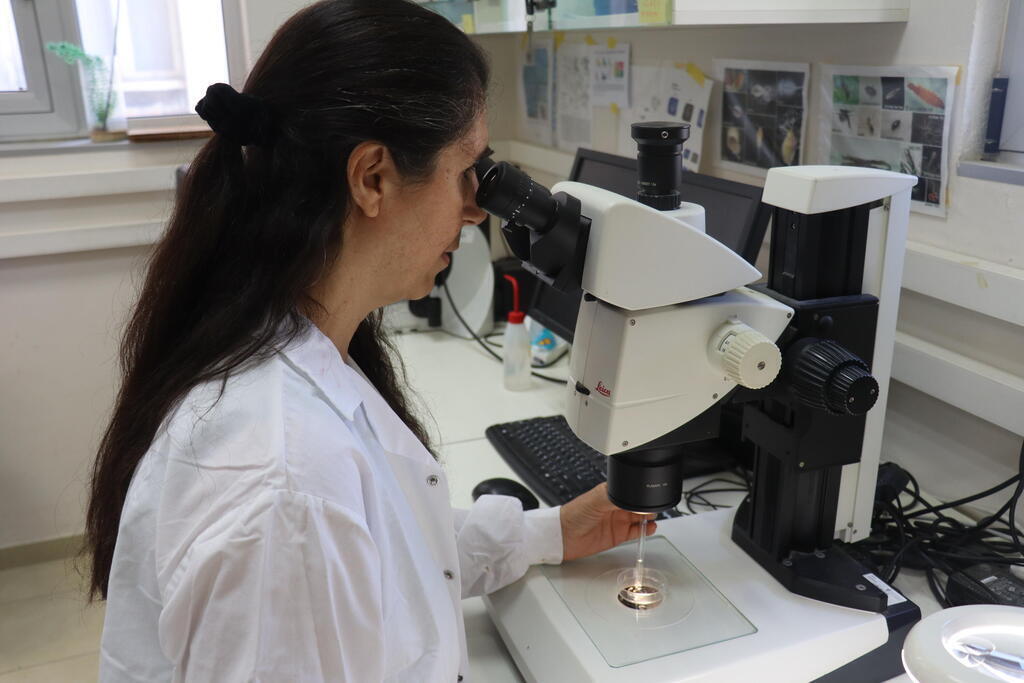

A Tel Aviv University study reveals that parasites in nature are not necessarily a bad thing and can even help animals survive. The study was conducted by Professor Frida Ben-Ami and Dr. Sigal Orlansky from the Tel Aviv University School of Zoology and the Steinhart Museum of Natural History. It was published in the Frontiers of Microbiology Journal

Read more:

"We usually have negative connotations when thinking of parasites, how they might impact their hosts? Or how damaging they are for those who carry them? In our research, we show that parasites actually have a positive impact on the structure of society and fill a key function in the design of the ecosystem and in its biodiversity."

A healthy ecosystem has a wide range of species living side by side, the researchers said. " Similar types can co-exist in society provided they impact or are impacted differently by resources or natural enemies. Without separation and a proper balance, they would not be able to exist, and one would become extinct. This is called the competitive exclusion principle or the Gause Law." They said.

"Disease-forming parasites are an integral part of every ecosystem. Despite their bad reputation, they fill a key role in designing the populations' dynamics and the biodiversity, as a result of their impact on the balance between the species," Dr. Orlansky said.

The study was conducted on 3milimieter-sized Daphnia crabs that can be found in Vernal pools. They feed on single-celled algae and bacteria and are themselves a food source for fish.

"Vernal pools are an enclosed habitat in which biodiversity is influenced by the competition of species. Aquatic species cannot leave or migrate elsewhere of their own volition making their success critical for their survival. They are also hosts or carriers of parasites and it is rare to find any that are completely resistant to parasites," Orlansy said.

"In the population in Israel, we found one type – called Daphnia Similis, or what we have named in the lab – a Super Daphnia, which is almost entirely resistant to parasites but is still not able to become the most prevalent in the pools. The Daphnia Magna, which is very vulnerable to parasites is the more commonly found type," Professor Ben-Ami adds.

To understand why being immune to parasites has not resulted in more dominance, the researchers built a microcosm in their lab, where both types shared the same habitats, one with and one without parasites. The results quickly showed that in the habitat without parasites, the more vulnerable species, and the more common in nature, ultimately succeeded in competing and the more resistant Daphnia, disappeared.

But in the habitat that contained parasites, the more vulnerable Daphnia dropped in numbers dramatically while the population of the Super Daphnia was well established, resulting in the coexistence of both types.

Professor Ben Ami said in her summary conclusions that the experiments made a significant contribution to the understanding of ecosystems where both types exist with ramifications that could affect the way to deal with invasive biological species and even assist in reducing the threat to endangered species.