Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

One of the apex predators that roamed the Earth 230 million years ago, had a bite much weaker than previously thought, suggesting that they couldn't easily penetrate bones to kill their prey.

More stories:

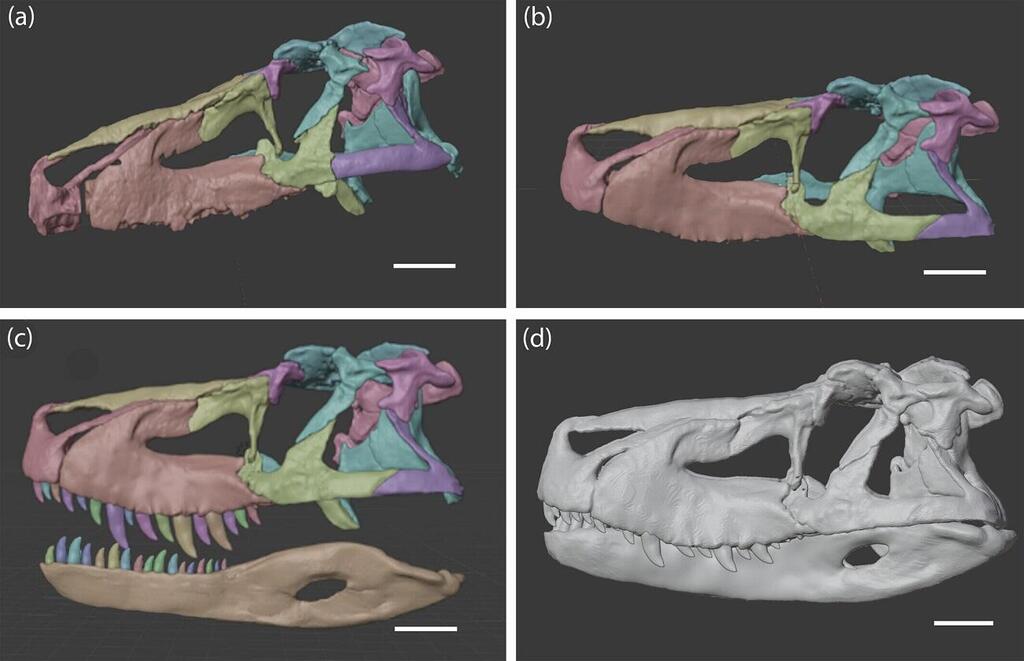

In a new study published in The Anatomical Record journal, paleontologists from the University of Birmingham reconstructed the anatomy of the original skull of the saurosuchus, an extinct large reptile from the Upper Triassic period. It belonged to the archosaur group and was closely related to the distant relatives of modern crocodiles, resembling them in appearance.

3 View gallery

Reconstruction of a saurosuchus and its skull

(Photo: Jordan Bestwick, University of Birmingham)

Saurosuchus, which lived on land, was considered an apex predator due to its size and diet. Its body length ranged from 5 meters to 8 meters, and its weight was estimated to be over 250 kilograms.

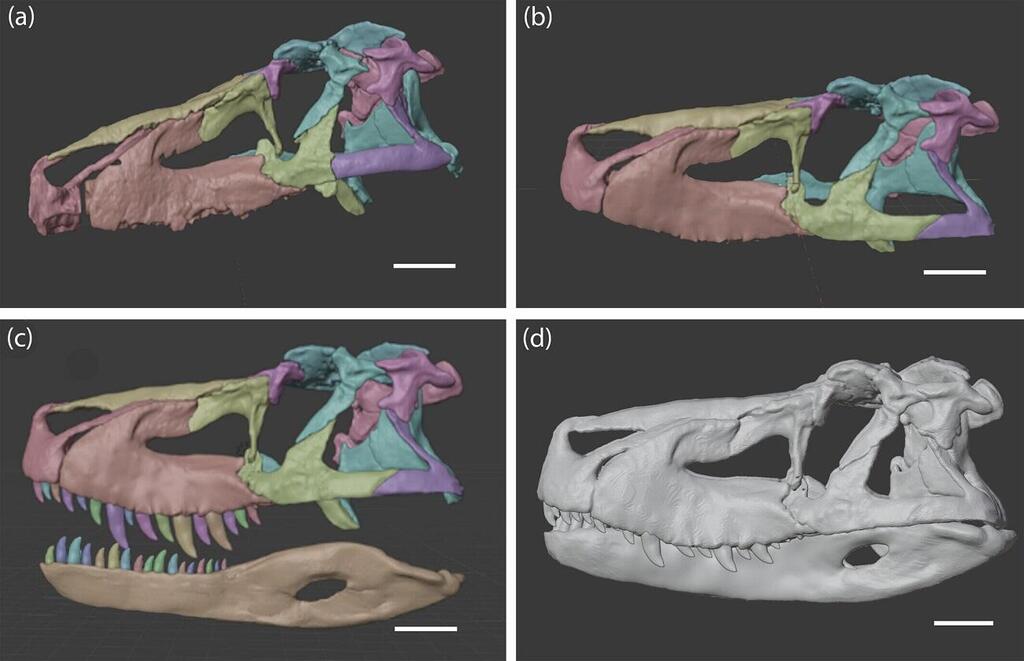

However, through the latest analysis of the reptile's skull, which was one of the larger early archosaurs, along with comparisons to allosaurus – a predatory dinosaur that lived in the late Jurassic period and was also large in size (9 meters in length and weighing 2 tons) – scientists discovered that despite the significant resemblance between the skulls, the saurosuchus' bite force was much weaker compared to the dinosaurs that came after it.

The saurosuchus' bite force was estimated to be around 1,015-1,885 newtons (a unit of measurement used for measuring force), equivalent to that of modern crocodiles in the Gavialidae family.

For example, the bite force of allosaurus is estimated at 3,572 newtons, while that of a saltwater crocodile reaches 16,000 newtons. On the other hand, the formidable tyrannosaurus rex had a bite force ranging from 17,000 to 35,000 newtons.

“We found that saurosuchus galilei actually had an incredibly weak bite for its size and thus predated animals in very different ways compared to later evolving dinosaurs,” said Dr. Jordan Bestwick, a palaeobiologist from the University of Birmingham and one of the study's authors.

“In fact, despite being one of the bigger lizards and an apex predator, saurosuchus galilei had a bite that was on a par with the relatively measly bite of the gharial, and much less powerful than more fearsome crocs and alligators around today," he added.

“You would still have liked to leave saurosuchus galilei well alone, but they likely fed only on the soft fleshy bits of their kills as their bite wouldn’t have enabled them to crunch up bones.”

Despite its relatively large size, the saurosuchus used its rear teeth to strip the flesh from its prey. Unlike later dinosaurs, this feeding behavior appears to be a result of its weak bite and its skull's relatively rectangular shape.

3 View gallery

Reconstruction of a saurosuchus skull compared to that of an Allosaurus

(Photo: The Anatomical Record (2023). DOI: 10.1002/ar.25299)

Furthermore, these early reptiles had thinner bones in their snouts compared to allosaurus, which lived at the end of the Jurassic period and was the most common apex predator in its environment.

“Saurosuchus galilei would certainly have been a fearsome reptile until it sat down to eat its prey, and we can see how evolutionary details in the skulls of these massive apex predators necessitated significant differences in eating behavior,” said Dr. Stephan Lautenschlager, a palaeobiologist from the University of Birmingham and one of the study's head authors.

“While dinosaurs that followed in the Jurassic period would have eaten the vast majority of their kills, saurosuchus galilei may have left more complete carcasses, which would have provided a secondary meal for carrion-feeding animals too," he added.

“It is truly amazing how similar the skulls of top predators in the Triassic period (the time before the domination of the dinosaurs) look compared to the well-known carnivorous dinosaurs such as tyrannosaurus rex,” said Molly Fawcett, who also participated in the study.

“However, unexpectedly we found that the bite power of these Triassic predators were far weaker compared to the post-Triassic dinosaurs.”