Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Before the arrival of humans, New Zealand was a realm of birds. Possibly due to the land being largely submerged during the Oligocene era, which spanned between 34 and 24 million years ago, land mammals were completely absent from the fauna. The only mammals present were those that could fly (bats) or swim (seals, dolphins).

Read more:

The ecological niche (the specific role a species plays within its community) of grazers, such as deers, llamas and antelopes, was occupied by a unique group of birds: the moa. The nine species of moa differed dramatically in size, with the smallest being roughly the size of a turkey, while the largest, the South Island Giant Moa, could reach a height of 3.6 m and weighed up to 250 kg, making it the tallest and the second heaviest bird known to have ever existed, surpassed in weight only by the extinct elephant bird.

4 View gallery

The giant moa, a bird species native to New Zealand, encompassed a group of large, flightless birds that formed a prominent part of New Zealand’s avian fauna until their extinction; Depicted here on a postage stamp, it remains a symbol of New Zealand's unique natural history

(Photo: Shutterstock)

Evolution of the moa

The origins of the moa, specifically when and from where its ancestor arrived in New Zealand, remain a mystery. Recent genetic studies found that the moa is most closely related to the tinamou, a small South American bird, suggesting that the ancestors of the moa may have evolved in South America.

Upon arriving in New Zealand, the ancestral moa underwent a remarkable diversification process, which gave rise to nine distinct moa species, occupying different habitats such as grasslands, forests and alpine regions.

Due to the absence of mammalian predators, the moa had no need to hide, which allowed them to grow very large. Since the moa had no need to be able to escape land predators, they eventually lost their ability to fly and had absolutely no wings. The only predator of the moa was the rare Haast’s eagle, a carnivorous bird with a wingspan of up to 3 meters.

Extinction of the moa

Around the year 1300, the first people arrived in New Zealand. Eastern Polynesian sailors navigated through the South Pacific and established their settlements on the land. Though their initial encounter with the giant birds was likely quite terrifying, humans quickly learned that the moa were unaccustomed to land predators and incapable of self-defense, making them easy prey.

4 View gallery

Due to the absence of land predators, the moa grew very large and eventually lost their ability to fly; Illustration of giant moa next to a river

(Photo: C048/9567, MARK P. WITTON / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY)

Moa were plentiful and served as a great source of food, and were hunted with spears and traps. Their feathers were utilized to make cloaks, their bones were crafted into spearheads and ornaments. In addition to consuming adult moas, their eggs were exploited both as a food source and for making water carriers.

Unlike most Polynesian birds that are characterized by a short lifespan and are quick breeding, the moa had a life expectancy of 50 years and laid only one or two eggs per year. Due to the relentless hunting of both the eggs and adult females, the population had no time to recover. Within merely 200 years of the arrival of the first humans, all moa species became extinct.

Reconstruction of the physiology and behavior of the moa

The extinction of the moa occurred about 500 years ago and is considered recent when juxtaposed with other notable extinctions, such as that of the woolly mammoth. The relative recency of the extinction also allowed for a variety of remains to remain preserved, including skin, feathers, muscle tissue, internal organs and even tongue and mummified eyeballs. These allow scientists to understand the anatomy, physiology and even the potential behavior of this giant bird.

4 View gallery

The South Island giant moa was likely the tallest birth that ever lived, reaching a height of 3.6 meters and weighing about 250 kilograms; Hunting by newly arrived humans is thought to have led to their extinction within merely 200 years; Illustration of an early human hunting the giant moa

(Photo: C052/7318, SCIENCE SOURCE / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY)

Archeological findings of intact tracheal rings enabled scientists to get an idea about the potential vocalizations of the moa. The tracheal rings allowed for the reconstruction of the form and structure of the bird’s windpipe, which was longer than its neck and formed a loop beneath the neck region.

Birds with similar windpipe structures, such as cranes and swans, produce deep, resonant calls. Scientists presume that the moa were likely highly vocal, their deep calls reaching long distances. They likely used situation-specific calls, such as alarm calls and mating calls.

The South Island giant moa, as well as most of the other moa species, displayed extreme sexual dimorphism - evident differences in the physical appearance between males and females. Females were about 150% taller and 280% heavier than males, a factor that led many to believe for an extended period of time that they were distinct species.

The sexual dimorphism extended beyond physical appearance, and was also apparent in the moa’s behavioral patterns. Females likely competed aggressively for males, while males were tasked with guarding and incubating the eggs.

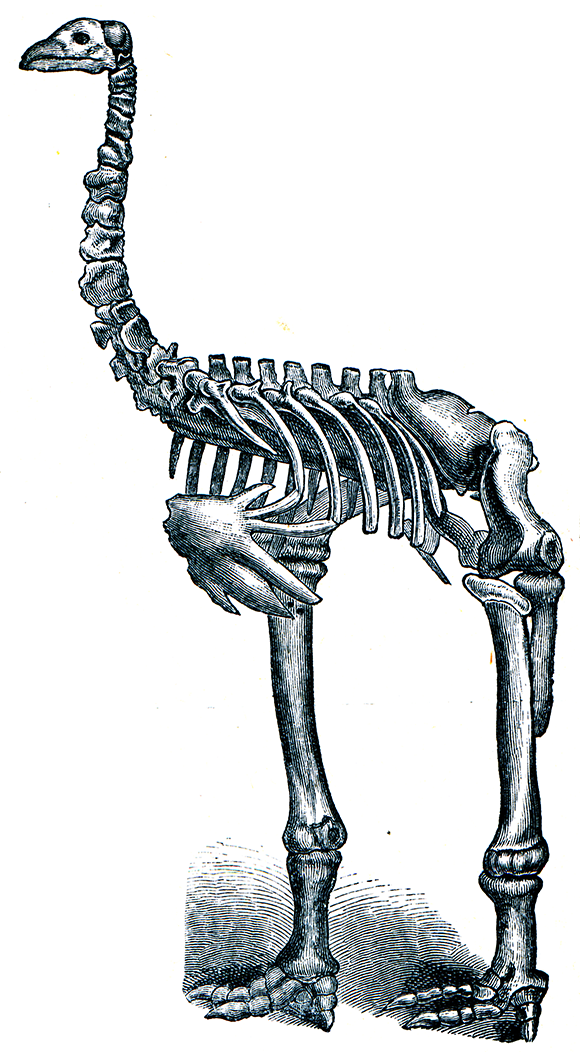

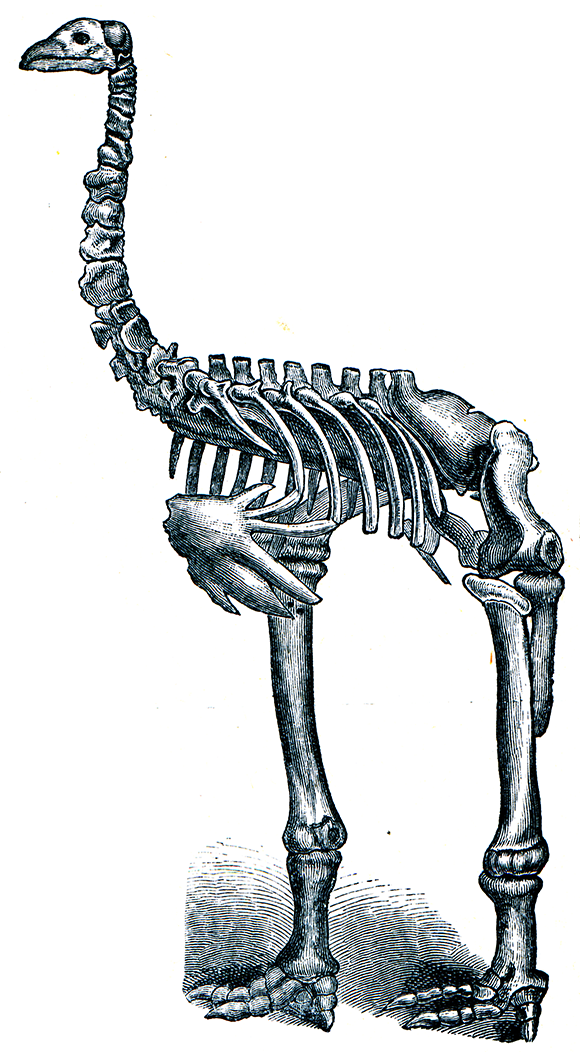

4 View gallery

Archeological findings of moa tracheal rings lead scientists to believe that the moa were likely highly vocal birds, their deep resonant calls likely reaching long distances; Skeleton of the giant moa - a vintage illustration from Meyers Konversations-Lexikon 1897

(Photo: Hein Nouwens, Shutterstock)

The eggs of the Southern Island giant moa weighed around 4 kg. The egg had a thin, 1.4 mm shell, making it the most fragile egg among birds. Instead of incubating their eggs by sitting on them, moa likely wrapped their lengthy necks around the eggs for warmth.

De-extinction of the moa

The relatively recent extinction of the moa and ample preserved DNA make the species a prime candidate for de-extinction, the resurrection of extinct species using advanced molecular biology. Biologists have successfully reconstructed the genome of a small bush moa from a museum specimen and experiments are currently underway to introduce selected genes of the South Island giant moa into chicken embryos.

While the practicality of de-extinction is highly debated, using modern technology to better understand the life of this fascinating bird can bring attention to the necessity of nature conservation and stopping the ongoing, human-caused extinction event.