Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The past few years have been marked by challenges that have underscored the need for collective responsibility and mutual solidarity as essential components of societal recovery. From geopolitical tensions and economic instability to natural disasters and global health crises, the world has faced interconnected threats that test our ability to cooperate.

Amid these challenges, the climate crisis has only intensified. Extreme weather events, from devastating wildfires to catastrophic floods, have wreaked havoc across continents, impacting entire communities, straining economies, and repeatedly breaking temperature records, while greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated.

6 View gallery

Map displays global temperatures from June 2023 to May 2024 compared to the 1991-2020 average. Areas in red indicate significant warming across most of the globe

(Photo: Copernicus Climate Change Service/ECMWF)

Moments of reflection offer us a chance to seek both personal and collective reckoning on issues that profoundly impact our lives, including the climate crisis. This reckoning begins with acknowledging the harm done and accepting responsibility for our part in it.

Without assuming responsibility, we cannot expect resolution—from ourselves or others—nor can we begin to make amends. As a society, we all share responsibility for the climate crisis, but it’s essential that this responsibility is shared fairly among social sectors and does not lead to excessive self-blame or destructive blame-shifting.

An imprint of responsibility

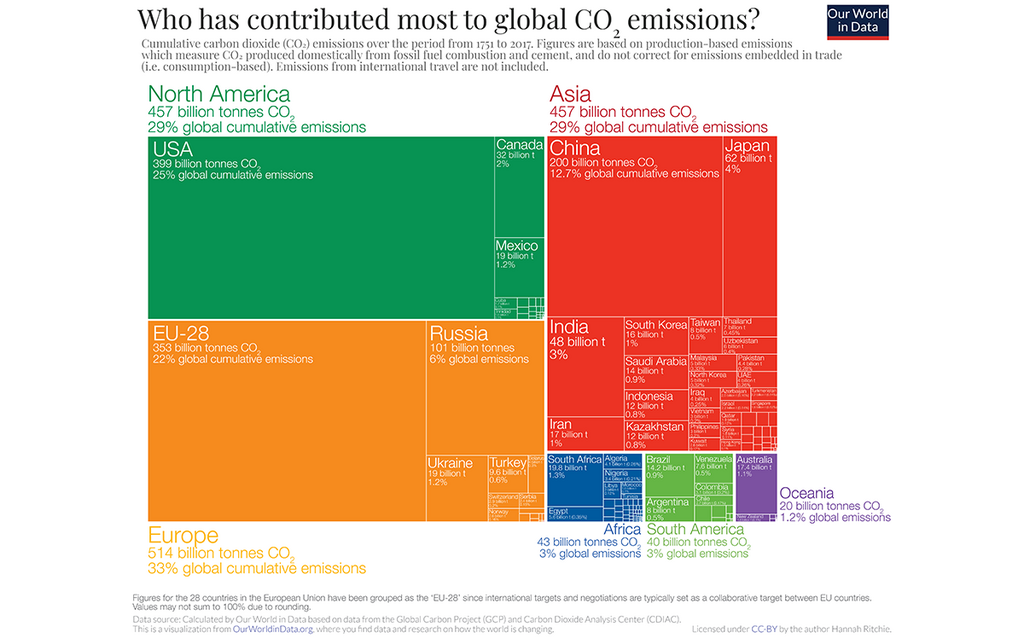

The concept of a carbon footprint is central to determining responsibility for the climate crisis. At first glance, it seems straightforward: carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases drive the climate crisis, so those who emit them bear responsibility. The more emissions a country, company, process, or product generates, the larger its carbon footprint—and, by extension, the greater its responsibility for the crisis.

Scientists, economists, and engineers have spent years refining methods to measure and evaluate carbon footprints. We now understand both the main sources of greenhouse gases and the potential reductions achievable if we acted collectively. However, building social consensus around the implications of these emission figures remains a significant challenge.

One of the greatest challenges in addressing the climate crisis is achieving consensus among world leaders. Each national leader, by virtue of their role, is accountable for their country’s greenhouse gas emissions and holds the authority to reduce them through various policies—whether by imposing taxes or restrictions on polluters or by investing directly in sustainable solutions like renewable energy production instead of fossil fuels. While any emission reduction benefits the environment, coordinated global efforts are essential to halt global warming and mitigate its most severe impacts.

However, these necessary measures come with economic and political costs, prompting many leaders to interpret even the clearest data in ways that allow them to evade responsibility and shift the burden to other nations.

This is precisely what U.S. President George Bush did in 2001 when he dismantled the Kyoto Protocol - the world’s most important emissions reduction initiative at the time - stating, “I oppose the Kyoto Protocol because it exempts 80 percent of the world, including major population centers such as China and India, from compliance, and would cause serious harm to the U.S. economy. The Senate's vote, 95-0, shows that there is a clear consensus that the Kyoto Protocol is an unfair and ineffective means of addressing global climate change concerns.

Despite Bush’s statement, the U.S. was responsible that year for nearly a quarter of the world’s total carbon dioxide emissions—60% more than China and six times more than India. Furthermore, his statement dismissed U.S. responsibility for its past emissions and ignored the stark inequality in per capita emissions. The Kyoto Protocol focused on wealthy countries because they had been the primary emitters of greenhouse gases since 18th-century industrialization and thus possessed the practical means to mitigate ongoing warming.

One of the issues with carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere is that the warming effect of the carbon persists for at least hundreds of years after being released. The carbon cycle, through which CO₂ is emitted into the atmosphere and then reabsorbed by soil, rocks, water, and vegetation, involves multiple processes. Only the slowest of these processes will fully remove the excess carbon from the atmosphere. According to oceanographer David Archer from the University of Chicago, when carbon dioxide is released from burning fossil fuels, it doesn't simply disappear from the atmosphere in a short time frame - instead, a significant portion of it remains in the atmosphere for several centuries and a quarter of it remains there essentially forever.

Although China currently emits more carbon dioxide than any other country, its cumulative emissions over the past centuries amount to just 13% of the global cumulative emissions. By comparison, the contributions of the U.S. and Europe to cumulative CO₂ emissions are double that. And India? Despite being the world's most populous country, it accounts for only about 3% of global cumulative emissions.

The Per Capita Emissions Consideration

While President Bush lamented the impact on the U.S. economy—the world’s strongest—nearly 40% of the populations of China and India, close to a billion people, were living in extreme poverty, earning less than $2.15 a day, according to the global poverty line. Emission metrics that fail to consider population size do not provide a fair or accurate picture and are therefore misleading.

6 View gallery

Carbon dioxide emissions across various countries relative to population size

(Photo: Our World in Data)

In theory, any relatively small country could pollute recklessly and deny responsibility by arguing that its total emissions are negligible compared to those of giants like China or the United States. However, much of the world’s emissions actually come from countries often seen as "less significant.” A fairer way to assess national impact is by examining emissions per capita. Additionally, if a country imports goods produced elsewhere, it should also share responsibility for the greenhouse gases generated during production—not just the producing country—since those goods are made for its consumption and benefit.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

If we divide global carbon emissions by the total world population, we arrive at nearly five tons of carbon dioxide per person per year. Yet, the distribution is far from balanced. In the European Union, total emissions amount to about eight tons per person; while in the United States, the figure is roughly 16 tons per person. China, having significantly reduced extreme poverty, now emits about seven tons per capita, while India, still grappling with widespread poverty, emits under two tons of carbon dioxide per person annually.

In other words, the relative contribution of affluent countries to the climate crisis far exceeds their share of the world’s population, and so does the moral and practical responsibility they bear.

Balancing personal and systemic responsibility

We all share responsibility for the climate crisis and must do everything within our power to mitigate it. One approach assigns each of us a personal carbon footprint based on our activities, encouraging us to "do our part" to reduce individual emissions. However, this focus can place an unfair burden on individuals while overlooking the need for systemic change, which is essential to effectively combat global warming. Without large-scale, coordinated actions, an overemphasis on personal responsibility is unlikely to halt global warming and may lead to frustration and a sense of helplessness.

That said, it is important to reduce the carbon emissions directly related to our behavior, and tracking our carbon footprint can help us make meaningful changes. For instance, burning fuel for transportation is a major source of carbon dioxide emissions. Driving a private car causes twice as much greenhouse gas per passenger-kilometer as taking a bus and four times as much as taking a train. Choosing alternative transportation can therefore significantly reduce our contribution to the climate crisis.

The problem is that many people do not have access to public transportation that meets their needs and are forced to rely primarily on private vehicles. Should they be held responsible for the emissions from their commutes? Or should policymakers bear the blame for not allocating sufficient resources to develop affordable and accessible public transportation networks, which makes it difficult for people to leave their cars at home?

Moreover, are we responsible for the emissions from the electricity we consume, or is responsibility better placed on government policies that continue to prioritize coal and gas? While individuals do bear some responsibility, our freedom of choice regarding most emissions is often limited, leaving us with no option but to choose polluting alternatives against our will.

Emphasizing personal responsibility in the climate crisis can be misleading and even harmful, as it diverts attention from the systemic reforms required at a societal level. This approach notably benefits certain stakeholders, particularly oil and gas companies. These corporations, which earn hundreds of billions of dollars annually from the sale of polluting fossil fuels—the primary source of greenhouse gas emissions—have invested heavily in public relations campaigns to embed the concept of a "carbon footprint" in the public consciousness, and they have been remarkably effective.

According to Benjamin Franta, then a student of law and the history of science at Stanford Law School and Stanford University and now Associate Professor of Climate Litigation at the University of Oxford, "This is one of the most successful, deceptive PR campaigns maybe ever," Geoffrey Supran, then a science history scholar at Harvard University and now Associate Professor of Environmental Science and Policy at the University of Miami, who has studied the practices of oil and gas companies, added, "This industry has a proven track record of communicating strategically to confuse the public and undermine action, so we should avoid falling into their rhetorical traps."

While oil and gas companies promote the narrative that ordinary people are responsible for the crisis, they employ thousands of lobbyists to obstruct policymakers worldwide from initiating necessary changes. Nevertheless, we have a path toward accountability, taking responsibility, and changing our ways.

A social turning point

To truly take responsibility, we must acknowledge that we emit more greenhouse gases than the global average simply because we live in wealthy, developed countries. Even with our best efforts, most of us cannot reduce our emissions by half on our own to match the global average. And as for the ultimate goal—net-zero emissions—that is far beyond what individuals can achieve alone. However, what we can do is drive systemic change that enables significant emissions reductions across our countries, going beyond just our personal share.

6 View gallery

Protesters in Australia call for urgent action to address the climate crisis

(Photo: Shutterstock)

Author and environmentalist Bill McKibben explains it this way: “Say you have a certain amount of time and money with which to make change — call it x, since that is what we mathematicians call things. The trick is to increase that x by multiplication, not addition. The trick is to take that 5 percent of people who really care and make them count for far more than 5 percent. And the trick to that is democracy.”

McKibben emphasizes that even a committed minority can, through collective actions like protests, petitions, voting, and open dialogue, push decision-makers to implement broad-scale changes. Beyond advocating for policy shifts, individuals can make a difference personally by leading within their social circles—promoting eco-friendly technologies such as electric vehicles or rooftop solar panels, shifting investments from polluting industries to sustainable alternatives, and encouraging social norms like reducing food waste and cutting back on high-impact foods like beef. Often, these pioneering efforts can trigger positive feedback loops, where change spreads quickly through society, reshaping reality.

Mutual solidarity

In times of war, global pandemics, economic turmoil, or environmental disasters, mutual solidarity becomes crucial for navigating crises, maintaining resilience and hope, and encouraging collective accountability.

At the official level, countries worldwide acknowledge this need, particularly in discussions around climate crisis mitigation. Alongside collaborative efforts to reduce emissions—where some wealthy nations have set ambitious goals—last year marked the creation of an international fund to compensate poorer countries, expected to face the harshest impacts of the climate crisis.

Despite only a small fraction of the needed funds being raised so far—about 400,000 of the required 100 billion annually—the establishment of this fund represents a significant and meaningful and important step.

Mutual solidarity does not begin or end at the governmental level, and it is worth considering it as part of the process of reckoning and self-reflection. Recognizing the suffering of others, supporting impacted communities, and fostering proactive preparedness can help vulnerable regions better handle anticipated challenges. Initiatives like urban resilience programs, stronger disaster insurance frameworks, and the restoration of natural protective ecosystems are just some practical steps we can take.

Cultivating mutual solidarity involves more than practical measures; it requires nurturing trust, empathy, and a shared commitment to collective well-being, through caring interactions, meaningful encounters, and mutual understanding.