At the end of 2021, nearly thirty years after immigrating to Israel from Ukraine, Victoria and Sergey Gredeskul decided to return. Both were approaching the age of 80 and wanted to be closer to their daughter and grandson who live there.

However, their trip was delayed as they were unable to sell their house in Ofakim, as planned, where they had lived for almost all their years in Israel.

In February 2022, when the Russian army invaded Ukraine, their plans to travel were canceled. "When the war broke out, we said, 'How fortunate that Sergey stayed in Ofakim,'" recalls his colleague, Prof. Victor Kagalovsky, dean of the Faculty of Engineering at the Sami Shamoon College of Engineering (SCE) in Be'er Sheva. "We were relieved, but in the end, it ended very tragically."

Not simple mathematics

Sergey Gredeskul, or Seryozha as his friends called him, was born on March 12, 1942, in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg), where his parents had been evacuated from Ukraine following Nazi Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union.

Later, the family returned to Kharkiv, Ukraine, where Sergey’s father, Andrei, became a professor and head of the Department of Automobiles at the Kharkiv National Automobile & Highway University, which has since been renamed in his honor. His mother, Bella, worked as a traffic inspector and was also a talented pianist.

From a young age, Sergey stood out as an exceptional student and gifted musician, playing the piano like his mother. Friends recall that at the end of high school, he was torn between pursuing physics at university or music at the conservatory, ultimately making his decision based on the flip of a coin.

Whether the decision was truly random or more carefully considered, Sergey chose to study physics and mathematics at Kharkiv University, one of the Soviet Union’s premier institutions at the time. He studied under world-renowned researchers such as Alexandr Akhiezer, Volodymyr Marchenko, Mark Azbel and Ilya Lifshitz.

Sergey completed his studies in 1964, then pursued a master’s degree under Lifshitz's supervision, followed by a Ph.D. in theoretical physics at the Ukrainian Physics and Technology Institute (UPTI), completing it in 1970.

Victoria Gredeskul (née Semenenko) was born on August 16, 1942, to government employee parents. She studied physics at Kharkiv University, where she met Sergey. The couple married in 1963, near the end of their studies, and in 1964, their only daughter, Tatiana (Tanya), was born.

Victoria initially taught physics and mathematics at the National University of Pharmacy in Kharkiv, and in 1968, she moved to the Institute for Low-Temperature Physics and Engineering (FTINT or ILTPE) in Kharkiv, where she completed her Ph.D. in physics, specializing in magneto-optics.

In 1970, Sergey also began working at FTINT after Lifshitz left Kharkiv for a position in Moscow. As a theoretical physicist, his research focused on solid-state physics, now known as "condensed matter physics."

He explored processes in disordered systems, such as non-crystalline materials or metals with impurities, examining how a metal's non-uniform structure or contamination by other materials affects electron transport and, consequently, the material's physical properties, including electrical conductivity.

In 1980, his work earned him the title of "Doctor of Science" (Доктор наук), an advanced academic degree that represented the highest academic qualification in the Soviet Union, awarded to individuals who had made significant, original contributions to their field and, recognizing them as leading experts in their scientific discipline.

During this period, he co-authored the book Introduction to the Theory of Disordered Systems with Lifshitz and Leonid Pastur, which was translated into English in 1988. The book summarized his and others' research, bringing structure to this pioneering field.

In 1985, the three authors received the State Prize of Ukraine in Science and Technology. "It’s an important and renowned book," remarked Prof. Yshay Avishai, a professor emeritus of the Department of Physics at the Ben-Gurion University (BGU), in a conversation with the Davidson Institute website. "They clarified the very complex mathematics of electron transport in disordered systems."

Superconductor

In 1991, around the time of the Soviet Union's collapse, Victoria and Sergey Gredeskul decided to immigrate to Israel following their daughter and her family. They were nearly 50 years old, but Sergey, a world-renowned physicist, believed he would have no difficulty integrating into a leading university.

Eventually, he joined the Department of Physics at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU) in Be'er Sheva, but not as a full faculty member. Instead, he was hired as a new immigrant scientist, defined as a temporary academic or research role specifically designed to support scientists who have recently immigrated to Israel, with his salary funded by the Aliyah and Integration Ministry. "His status was below his level," says Prof. Oleg Krichevsky, the current head of the Department of Physics at BGU.

However, Sergey integrated well into the department. Krichevsky, who is also originally from Kharkiv, had known the Gredeskuls since their time in Ukraine, where he attended the same university and was a classmate of their daughter, Tanya, among other family connections.

"Sergey’s work focused on electron scattering in metals, but the same principles also apply to light scattering in the atmosphere or ice crystals, for example. His research has broad implications in many areas of physics and engineering."

One of Gredeskul's close scientific collaborations was with Yshay Avishai, who was responsible for his integration into the university. "We worked together and published joint papers. Among other things, we examined the effects of a strong magnetic field on quantum effects in a two-dimensional conductor, essentially a thin sheet of material."

Since Gredeskul was not a full-fledged researcher, he was not authorized to independently supervise research students, but he was a co-supervisor with other researchers for several students. "In our work with one of them, we won a research grant in the field of superconductors, which was new for him. We studied how their conductivity changes under conditions of disorder or due to external influences such as temperature changes," Avishai explained.

"The research grant was awarded to Avishai and Gredeskul along with Arkady Aronov, an expert in superconductors, who, unfortunately, passed away shortly after receiving the grant to study the effects of disorder on vortex behavior in superconductors," Krichevsky recounted. "Sergey and his research student, Gregory Braverman, began learning the subject from scratch. The result was a series of brilliant papers on the behavior of several types of superconductors.”

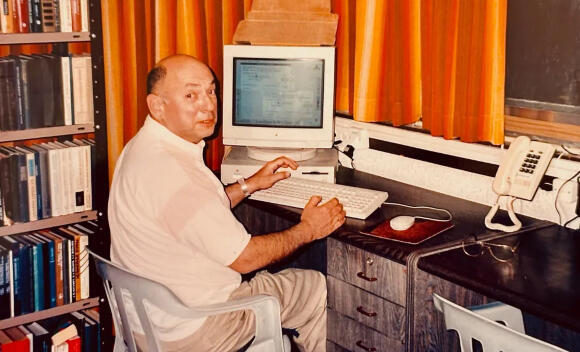

7 View gallery

Gerdeskul, Prof. Yshay Avishai and Gregory Braverman

(Photo: Courtesy of Gregory Braverman)

"He was an excellent researcher and helped many people. He had immense knowledge, and he was a good teacher. Thanks to him, I completed my doctorate," Gregory (Grisha) Braverman told the Davidson Institute website.

Braverman was a joint research student of Avishai and Gredeskul at BGU between 1994 and 1998. "When we got into the topic of superconductors, he would say, 'Let's learn this together.' We would read the papers and then analyze them together. He learned everything thoroughly and taught me to do the same - to delve deep and understand."

Gredeskul's assistance to others wasn't limited to physics. "When I was a student and my daughter was born, I bought an old Subaru," Braverman recalled. "He taught me mechanics and explained how to take care of the vehicle."

To his colleague Avishai, Gredeskul helped in a completely different field. "I started taking piano lessons at a relatively older age, at 40. When I had difficulties, Sergey would come to my house and help me with my playing."

A lecturer with a mission

Since he was not a full-time faculty member, Gredeskul was not required to teach at the university as part of his position, but he was very eager to do so. In the end, most of his teaching took place in the Mathematics Department.

"He was a beloved lecturer, and students would line up to register for his lectures, which were like theatrical performances," said Prof. Semyon Levitsky, now president of the Sami Shamoon College of Engineering.

Levitsky, who taught with Gredeskul at the Mathematics Department at BGU, told the Davidson Institute website, "We worked together on the syllabi for the courses and on the exams. He was very meticulous – he wanted every statement in his lectures to be clear to the students and for the syllabus to be consistent, with every new piece of information building on prior knowledge. We also worked hard on every exam, and I was deeply impressed by his commitment to ensuring that everything was understood without a shadow of a doubt. He truly saw teaching as a mission."

In addition to his dedication to teaching, Sergey was always attentive to students' questions. "He was approachable, and students could always come to him for advice and questions," Levitsky added. "Although he was a world-class physicist, he made sure his colleagues never felt there were gaps between him and them. He was a mensch. He also invested a lot in research and had extensive knowledge. Although he primarily taught mathematics courses, he could teach any subject."

"He learned Hebrew well, overcame the language barrier and students loved him very much," added Avishai. "He was a gentle, humble and quiet person, never shouting or aggressive, and always willing to help."

"I consulted him a lot during my studies, and with his help, I even managed to attend an important conference," said Victor Kagalovsky. "In fact, I first met him in Ukraine when I was finishing high school, and he was already a renowned researcher at the Institute for Low-Temperatures Physics while also teaching at the university. I sought his advice on studies, and when I began my doctoral studies at Ben-Gurion University, I met him there again. He remembered me from Ukraine, and I continued to rely on his support in Israel."

Broad horizons

Shortly after immigrating to Israel, the Gredeskuls bought a house in Ofakim—a half-duplex on Hagoren Street in the city's western part. Sergey tended to the small garden, and the couple enjoyed hosting many colleagues and friends in their home.

They remained in Ofakim even after their daughter returned to Ukraine a few years later when her mathematician husband couldn't find work in Israel. Although Victoria did not integrate into academia as Sergey did, she secured a position as a teaching assistant in the Mathematics Department at BGU, where she continued until her retirement.

"Sergey was happy here. He had a good life. Victoria also enjoyed her work at the university," said Prof. Yuri Kaganovsky, a close friend of the couple who followed a similar path to Sergey’s – at Bar-Ilan University – speaking to the Davidson Institute. "They were a close couple. Victoria took on the household tasks to allow Sergey to focus on his career. She was an open, kind and very pleasant woman who loved to help everyone."

Kaganovsky knew Victoria from their school days, and later met Sergey when all three studied together at university. "I was at their wedding, and many times we would go together for summer vacations in cabins by the seashore. He was a brilliant physicist, but when we met, we didn’t talk about physics. We talked about life, friends and art. He was a man of culture."

Anyone who visited the Gredeskul home in Ofakim was struck by Sergey’s extensive music collection—records, CDs and sheet music. "He was an exceptionally skilled pianist, truly an expert. He could identify the differences between musicians or ensembles playing the same piece and explain the distinctions," Kaganovsky added. "He also had fascinating stories about his encounters with musicians, and at social gatherings, he was always the center of attention."

Another signature of Sergey Gredeskul was the red Opel he bought upon arriving in Israel and never replaced. "That was his philosophy: as long as the car runs, you don’t replace it," said Prof. Oleg Krichevsky.

His friend Kaganovsky added, "Sergey always had a car, and he was our driver when we went on vacations together. In Ukraine, it's not customary to replace a car every few years like it is here. Sergey, the son of a professor of automotive engineering and a traffic expert, never parted with the car he bought, performing all the repairs and maintenance himself."

According to Kaganovsky, Sergey wasn't only interested in car mechanics. "He used to build and fix things at home, for example, installing an irrigation system in the garden he loved. He had golden hands. Even in science, although he was a theoretical physicist, he worked extensively with experimentalists and assisted them with instruments and experiments."

Victoria and Sergey lived modestly but were passionate about culture. "They often went to the opera and never missed concerts," Kaganovsky said, with Avishai adding, "They attended many music events, and Sergey also read a lot of books. There was always something to discuss with him."

The couple also traveled abroad frequently, mainly to visit their daughter and grandson in Ukraine, and also Sergey’s younger sister, Olga, who moved to Australia with their parents. "He collaborated with physicists from Australia to visit his family there until health problems prevented him from traveling," Kagalovsky recounted. "He was very devoted to his family and financed his grandson Michael's studies at the University of Oxford."

A look back at history

Sergey Gredeskul published more than a hundred scientific papers throughout his career, continuing even after his retirement. "We continued to attend departmental seminars after retiring," Avishai recounted. "Sergey always had insightful and probing questions, but he knew how to ask them in a gentle and polite manner."

"When we established the college, I organized an academic colloquium here, and he would come and give outstanding lectures," said Victor Kagalovsky from the Sami Shamoon College of Engineering. "In recent years, he also began writing extensively about the history of physics in Kharkiv, for example, about the Institute for Low-Temperature Physics where he worked and where many important researchers worked and developed. He would lecture and publish articles on these topics. His last lecture at the college, in 2022, was still during the COVID-19 period, so it was held on Zoom. It lasted two hours, captivated the audience and even included researchers from Ukraine."

A sad ending

After the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the Gredeskuls abandoned their plan to return there, anxiously following developments, especially the situation of their daughter and grandson, who had left Kharkiv to distance themselves from the combat zones.

In February 2023, the couple celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary, just a few months after turning 80. They continued to live quietly in their home in Ofakim, enjoying music, culture, friends, and for Sergey – almost daily physical activity at the country club in Ofakim.

On October 7, 2023, among the many terrorists who breached the Gaza border fence and infiltrated Israel, 22 terrorists reached Ofakim from the open areas west of the city, near the Gredeskuls' home. They shot at everyone they encountered on the streets and then began going from house to house, murdering residents.

Twenty-seven civilians and six police officers were killed in the fighting in Ofakim, which continued even after terrorists barricaded themselves in the home of Rachel Edri, a local resident who managed to delay them until rescue forces arrived. Among the victims of the indiscriminate massacre were the Gredeskuls, who were murdered in their home.

"From the evidence, it appears that the terrorists did not enter the house but shot them from the yard, with Sergey in the living room. Victoria was shot a few steps away, likely as she exited the bedroom," recounted Kagalovsky, who arrived at the house with Krichevsky a few days after the massacre. "By the time we got there, the bodies had already been removed, but there were still bloodstains, bullet marks on the walls and AK-47 bullet casings in the yard," Krichevsky added.

The Gredeskuls' grandson and daughter contacted Krichevsky immediately when reports of the massacre in the communities near the Gaza Strip, including Ofakim, began spreading worldwide, especially after the couple did not answer phone calls or messages.

"They asked us to go to the house after the Ofakim municipality received an inquiry from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. They were informed that one of the victims was a well-known Soviet scientist, and requested his documents be sent to them. Their daughter, Tanya, was very worried that her parents' documents would end up in the hands of the Russians, whom they despised, and asked us to collect everything of scientific value from the house," Krichevsky explained.

"The computers, phones and personal documents we collected were handed over to the grandson. The scientific materials will be transferred to the physics department at the university once we finish sorting them."

Later, Sergey Gredeskul's piano was also moved from the house and placed in the Physics Department at BGU. "Students occasionally play it," Krichevsky added.

The identification of Victoria and Sergey Gredeskul's bodies took a long time. In their will, the couple requested to be cremated and have their ashes scattered in Kharkiv, their hometown. The cremation was delayed due to opposition from religious authorities, but it eventually took place," Krichevsky said. "However, due to the war in Ukraine, the ashes have not yet been transferred to the family and are currently being held in Israel."

It's simply a tragedy

Reports of the couple's death received minimal coverage in Hebrew media, which was inundated with other stories. However, they received more comprehensive coverage in Russian-language articles by journalist Nikita Aronov on the Russian website Meduza and the Ukrainian-Israeli website Detaly, where Aronov opened his article at the family's request with the words "Please, do not call him a Soviet scientist."

Another report on their deaths was published on the website of the scientific journal Nature, which, in November 2023, featured an article about Israeli scientists killed in the war, alongside coverage of damage to Gaza’s universities. The article sparked outrage in Israel due to the journal's choice to refer to Hamas as a "militant organization."

Over time, obituaries for Gredeskul and his work appeared in the scientific press, with more expected soon. Igor Kuzmenko, whom Gredeskul supervised during his doctoral work alongside Avishai and Konstantin Kikoin, added an obituary paragraph to a scientific paper submitted for publication.

"I was a new immigrant to Israel, and he helped me with both scientific research and the challenges of settling in. I am grateful for the opportunity to have known him and learned from him. He was a generous individual and an exceptional mentor. May his memory be a blessing."

"Sergey belonged to a generation focused on the work itself. He was interested in solving problems, not in honor or ego. He absorbed and preserved the unique atmosphere of Kharkiv, and now, sadly, it has vanished," said Levitsky. "It's simply a tragedy."

"Victoria and Sergey were like family to me. He was a man of broad horizons, and we would talk about art, music, theater. He was my best friend," Kaganovsky concluded. "It's hard to believe that a year has already passed without them. It’s very sad, and I miss them very much."

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: