Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

NASA has shut down three offices and laid off their employees as part of the first phase of cost-cutting and efficiency measures mandated by the administration. A total of 23 employees have been dismissed following the closure of NASA’s Office of the Chief Scientist, the Office of Technology, Policy, and Strategy, and the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

NASA Acting Administrator Janet Petro addressed the agency’s employees in a memo, explaining that the layoffs were carried out in accordance with federal workforce reduction directives. “In compliance with this directive, we are actively working with the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM) to develop a thoughtful approach that aligns with both administration priorities and our mission needs. While this will mean making difficult adjustments, we’re viewing this as an opportunity to reshape our workforce, ensuring we are doing what is statutorily required of us, while also providing American citizens with an efficient and effective agency.”

The Telescope That Will Observe the Dawn of the Universe

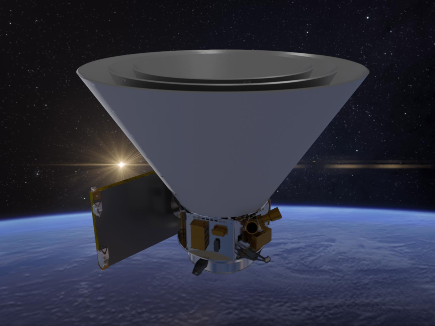

A new NASA space telescope was launched this week to explore secrets from the early days of the universe. The SPHEREx telescope was launched aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, into a 700-kilometer-high orbit that passes over Earth’s poles.

The telescope is designed to create a map of the sky with an unprecedented range of 102 separate wavelengths in visible and infrared light. Its observations will chart approximately 450 million galaxies, some as far as 10 billion light-years away. Additionally, it will survey around 100 million stars in our own galaxy, the Milky Way.

One of SPHEREx’s primary goals is to search for water and other small molecules essential for life as we know it, such as carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. Astronomers will examine whether such molecules exist in stellar nurseries (star-forming regions) and in the gas-and-dust disks around young stars, where planets form.

The telescope has a relatively small primary mirror, 20 centimeters in diameter. It is housed within a thermal shield made up of three nested cones. The outermost cone is over three meters wide and allows the telescope to operate at low temperatures—a crucial capability for infrared observations. One of the telescope’s goals is to use the data it collects to identify specific targets for more focused observations by other telescopes, such as the James Webb Space Telescope, which has far greater magnification and resolution capabilities. Researchers hope that combining SPHEREx’s data with observations from other instruments will help answer key questions about the evolution of the universe—especially when and where life-essential materials formed and how they spread across the cosmos.

SPHEREx is now entering a one-month calibration and testing phase. After that, it will embark on its two-year scientific mission, during which it is expected to map the sky four times. By comparing the resulting sky maps, researchers hope to extract even more valuable insights.

A secondary payload launched on the same rocket is PUNCH, a small-scale NASA mission consisting of four suitcase-sized satellites. These satellites will study solar activity and are intended to help scientists better understand how the solar wind — the stream of charged particles emitted from the Sun at high energies - is generated.

By operating the four satellites simultaneously, researchers aim to construct a 3D map of the Sun’s corona—its outer atmosphere—and of the heliosphere, the region influenced by the Sun and the solar wind, which encompasses nearly the entire solar system. The mission also aims to improve our understanding of solar storms and explain how powerful eruptions of solar wind occur—events that can also affect us here on Earth.

"What we hope PUNCH will bring to humanity is the ability to really see, for the first time, where we live inside the solar wind itself," said Craig DeForest, principal investigator for PUNCH at Southwest Research Institute’s Solar System Science and Exploration Division in Boulder, Colorado.

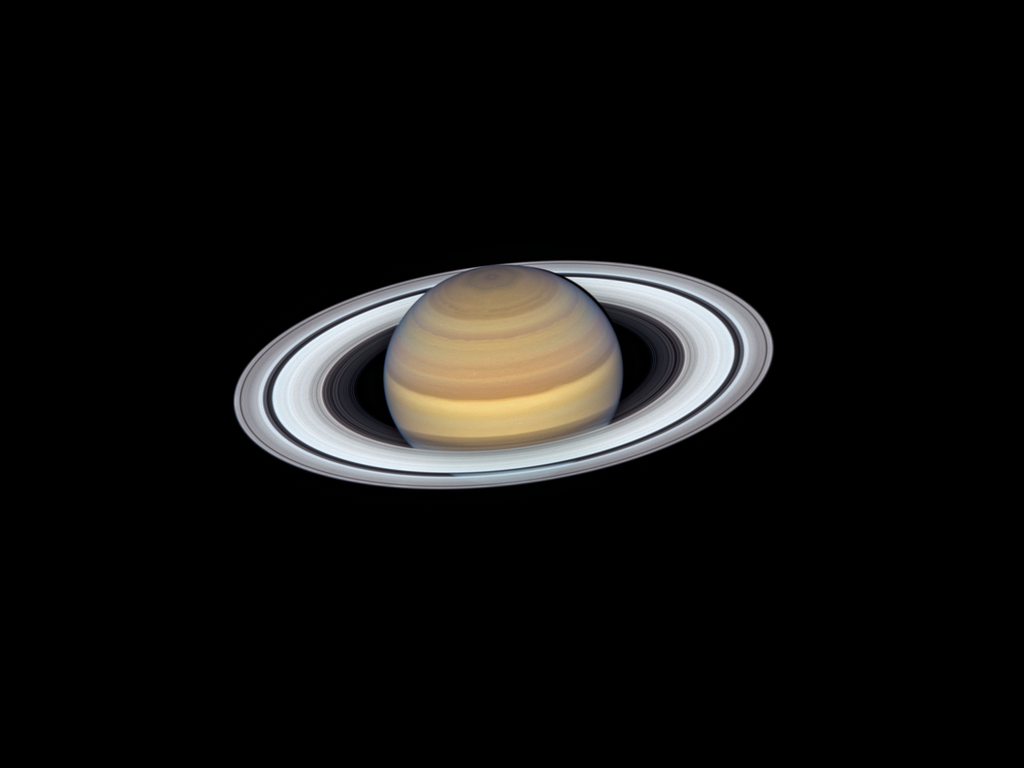

Saturn’s new moons

Researchers have discovered 128 previously unknown moons orbiting Saturn, bringing the planet’s total known moons to 274. The research team, led by Edward James Ashton from the Academia Sinica in Taiwan—who also took part in a previous discovery of dozens of Saturnian moons—identified the new moons using observations made in 2023 with a large ground-based telescope in Hawaii.

The newly discovered moons are quite small, with some measuring only a few kilometers in diameter. They follow unusual orbits: some have paths tilted at various angles relative to the plane in which most of Saturn’s moons orbit, while others orbit in the opposite direction of most of Saturn’s moons. Their orbits are also relatively distant, ranging from 10 to 30 million kilometers away from the planet.

The researchers estimate that many of these moons were formed through collisions between Saturn’s natural satellites. According to their assessment, 47 of the 128 newly identified moons likely originated from a single collision that occurred around 100 million years ago—a mere blink of an eye in cosmological terms.

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) has officially recognized the list of newly discovered moons, granting Ashton and his colleagues the privilege of naming them.

Shutting down instruments to extend Voyager’s life

After nearly 48 years in space, NASA engineers have begun to shut off scientific instruments on the Voyager spacecraft to conserve power and extend their mission.

Launched in 1977, the pair of spacecraft remain the only active probes to have exited the boundaries of the solar system. Last month, NASA shut down the cosmic ray measurement system on Voyager 1 and announced that it will also shut down the low-energy charged particle detector on Voyager 2 in the coming month.

“Electrical power is running low. If we don’t turn off an instrument on each Voyager now, they would probably have only a few more months of power before we would need to declare end of mission,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

Each of the Voyager probes are powered by three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), which provide power to the spacecraft by converting the heat generated by the decay of plutonium-238 into electricity. However, after decades in deep space, prolonged exposure to extreme conditions has caused the system’s performance to decline, reducing the probes’ power output by approximately four watts per year.

Each of the spacecraft is equipped with ten identical scientific instruments. Some were designed for the early phase of the mission—exploring the outer planets of the solar system—and were shut down after those objectives were completed to conserve energy. Both spacecraft flew past Jupiter and Saturn, after which their paths diverged. Voyager 1 headed toward interstellar space, crossing the boundary in 2012. Voyager 2 continued on to the planets Uranus (1986) and Neptune (1989), and in 2018, it was also confirmed to have exited the solar system. Today, Voyager 1 is approximately 25 billion kilometers from Earth, while Voyager 2 is about 21 billion kilometers away.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

In recent years, NASA has faced numerous malfunctions in the aging spacecraft, including issues with their computer and communication systems. However, engineers have managed to successfully overcome these issues so far. They now hope that gradually shutting down instruments will allow the spacecraft to continue operating for at least another year before further power reductions become necessary.

"The Voyager spacecraft have far surpassed their original mission to study the outer planets. Every bit of additional data we have gathered since then is not only valuable bonus science for heliophysics, but also a testament to the exemplary engineering that has gone into the Voyagers," said Patrick Koehn, Voyager program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

"Every minute of every day, the Voyagers explore a region where no spacecraft has gone before," added Linda Spilker, Voyager project scientist at JPL. "That also means every day could be our last. But that day could also bring another interstellar revelation. So, we’re pulling out all the stops, doing what we can to make sure Voyagers 1 and 2 continue their trailblazing for the maximum time possible."