Researchers at Ben-Gurion University have discovered the mechanism that allows cancer cells to survive despite lacking the glucose necessary for their existence. This discovery may pave the way for new treatments for various cancerous tumors in the future. The findings were recently published in the prestigious journal Nature.

"Living organisms feed on sugar to survive," explains Professor Barak Rotblat, one of the researchers and a lecturer from the Department of Life Sciences and the National Institute for Biotechnology in the Negev (NIBN) at Ben-Gurion University.

"This is true for humans, as well as other animals, plants and even bacteria. When we have a lot of energy, we produce fat, and when we have little left, we burn it. This is a very basic mechanism of nature that developed very early in evolution so that living creatures can maintain a proper energy balance. When the sugar levels in a cell drop below the threshold that allows its proper existence, this condition is called 'glucose starvation.'"

Cancer cells love sugar too. This characteristic is used in one of the common methods for diagnosing cancer metastases through PET CT scans, during which radioactive sugar is injected into the patient. Because cancerous tumors feed on sugar, the radioactive sugar accumulates in the tumor, making it visible in the imaging test.

However, one of the more interesting phenomena in this context is that, when measuring sugar levels in a cancerous tumor compared to healthy tissue, the tumor’s sugar levels are lower. "This is because the blood flow to the tumor is poorer than to normal tissue. Although the tumor grows blood vessels, they aren’t normal and leak. The second reason is because cancer cells love sugar very much, to the point that they consume every molecule they can obtain."

The question then arises: How do cancer cells overcome the lack of sugar and manage to survive and thrive? "This question intrigued us. We assumed that if we knew the mechanism that allows survival during glucose starvation, we could target it with drugs to affect starving cancer cells while sparing the healthy tissue cells that have sufficient sugar in them," Rotblat explained.

From this insight, a research group was formed in collaboration with Dr. Gabriel Leprivier from the University of Düsseldorf in Germany. The research team found that cancer cells enhance a common mechanism in mammals and even yeast, which allows them to overcome glucose starvation.

"We discovered that a protein called EBP4 regulates the rate at which the cell produces fat according to its energy status. When we observed the clinical data, we saw that this protein is produced at higher levels in cancer cells compared to normal tissue," Rotblat explains.

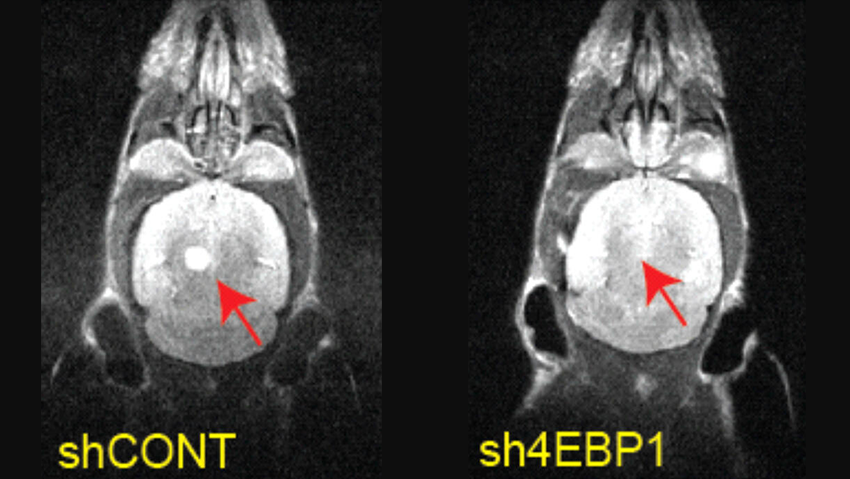

“We performed genetic manipulation and so disrupted the specific gene that causes the metabolic switch during glucose starvation, creating human, mouse and yeast cells with low levels of EBP4. We found that they don’t survive glucose starvation. Moreover, we discovered that when these cells are implanted in mice, not only do they fail to survive glucose starvation, but they are also impaired in their ability to form tumors,” he added.

"We observed that if we disrupt this mechanism in the cells, they live well under normal conditions, but if we starve them, they continue to produce fat even though they’re supposed to stop. The problem is that fat production consumes a lot of antioxidants. The fact that they continue to produce fat under starvation conditions means they consume antioxidants, which essentially causes them to burn themselves out."

This discovery is particularly interesting in the context of brain tumors, as the brain fluid contains very little glucose. Therefore, cancer cells in the brain need to be equipped with mechanisms that allow them to cope with glucose starvation.

"When we examined clinical data of brain tumors, we found that the gene encoding EBP4 is highly active in these tumors," Rotblat said. "We took cells derived from brain tumors, silenced the gene and implanted the silenced cells into the mice brains. The survival of the mice implanted with control cells was significantly lower than those implanted with EBP4-silenced cells, indicating that the gene contributes to the tumor's aggressiveness."

This could potentially lead to a treatment for some cancers in the future, according to Rotblat.

"Clinically, this could be a promising avenue for developing a cancer treatment. Together with BGN Technologies, the technology commercialization company of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, and with the support of the National Institute for Biotechnology in the Negev (NIBN), we’re currently working on developing a molecule that targets the EBP4 protein as a future treatment for cancers to induce glucose starvation and elimination, especially brain cancer."