Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The year is 331 BCE, and Alexander the Great is about to face one of the toughest and most decisive battles of his life, later to be remembered as the Battle of Gaugamela, in what is now northern Iraq. Facing him is the Persian army, which is far larger than his own.

Alexander knew he had to exploit every advantage, preparing himself and his army as thoroughly as possible. The Greek historian Plutarch described his actions: Alexander made a sacrifice to Phobos, the god of fear and son of Ares, the god of war, and instructed his commanders to motivate their soldiers by emphasizing that victory depended on each person performing their role to the fullest. When one of his officers asked if there was anything else he could do, Alexander replied, “Nothing, except to shave the Macedonians’ beards.”

Alexander shaved his own beard, and some suggest that his order for the entire army to shave their beards was to make his soldiers look like him. This, according to the theory, was intended to boost their morale and foster a sense of unity. Others, including Plutarch, offer a more pragmatic explanation: in close combat, a long beard could prove a dangerous liability, giving the enemy a convenient handhold.

Alexander’s army won the battle, paving the way for the conquest of the Persian Empire. The clean-shaven look he promoted spread to some extent in the Hellenic world, even among those outside the military. However, the practice of removal of facial hair did not begin with Alexander; it dates back thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of years earlier.

5 View gallery

Reconstruction of a mosaic depicting a beardless Alexander the Great at the Battle of Issus

(Enzo Pezzi, Cisem, Eurelios, SPL)

Shaving Among Prehistoric Humans

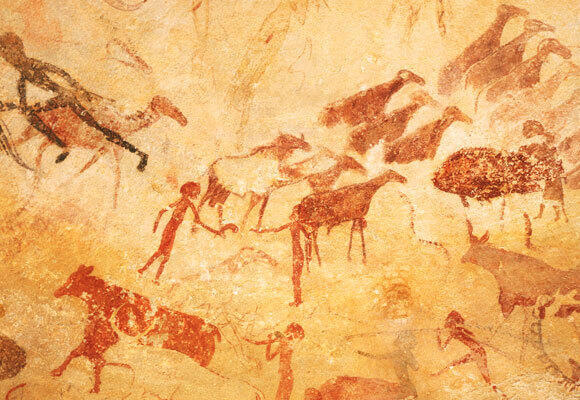

The exact origins of human shaving are unknown—when it began, how it was performed, and why remain subjects of speculation. Cave paintings dating back approximately 30,000 years, and even older, depict human figures without beards, which many researchers interpret as evidence of shaving or other forms of hair removal. But how did prehistoric humans achieve this? Our ancestors at the time lacked the knowledge of metalworking, making it extremely difficult to produce sharp stone tools suitable for shaving. It's possible that they simply trimmed their beards rather than removing them entirely, using flint or obsidian knives, a type of volcanic glass known for its sharpness. Alternatively, there may have even been other, less conventional methods.

The Muslim jurist and philosopher Muhammad ibn Idris al-Shafi'i, born in the 8th century CE, described encounters with a nomadic mountain tribe that used to pluck their beard hairs one by one using a tool resembling tweezers. Ancient humans might have employed similar methods, bypassing the need for especially sharp razors. For instance, they could have used two shells pressed together to pull out hairs. This wouldn’t have been a pleasant experience, but it might have been the only way to achieve a smooth face at the time.

Why did these ancient people seek to remove their beards? Health considerations could have been a significant factor. Health considerations could have been a significant factor. Additionally, when dirty, beards can harbor harmful bacteria. In an era when maintaining hair hygiene was challenging, removing facial hair may have been the most practical solution to these issues.

The Clean-Shaven Egyptians

Jumping to Egypt around 5,000–4,000 years ago, we find a culture almost obsessively focused on hair – on all hair. Men, women, and children shaved their heads and, if they had any, their beards, using rounded bronze razors. They also removed body hair, either by shaving or with special cosmetic products, and scrubbed their skin with pumice stones.

The Egyptians' focus on hair removal was deeply rooted in their high regard for body cleanliness. The Greek historian Herodotus, known as the “Father of History,” wrote about them in the fifth century BCE: “Their attention to cleanliness was very remarkable, as is shown by their shaving the head and beard, and removing the hair from the whole body, by their frequent ablutions, and by the strict rules instituted to ensure it.” According to Herodotus, the Egyptians washed themselves every day and twice every night and shaved their hair every two days.

In ancient Egypt, a shaved head and smooth face were symbols of high status, or at least indicators of not being of low standing. The poor didn’t shave frequently, likely struggling to obtain razors, as copper was very expensive in those days. However, there was one type of beard considered the ultimate status symbol, reserved solely for the Pharaoh. The “divine beard” of the Pharaohs was long, narrow, highly stylized – and entirely fake. Pharaohs wore it, likely to imitate the appearance of Osiris, the god who ruled the afterlife and was always depicted with a long, braided beard. By doing so, they sought to present themselves as living embodiments of the god on earth.

Within the pharaonic dynasty, there were also several female rulers, the first being Hatshepsut, who reigned about 3,500 years ago. She, along with some of her successors, is depicted in statues and paintings with intricately styled beards on their chins.

5 View gallery

A mask found in the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun shows a smooth chin except for a narrow, stylized beard

(Ann Ronan Picture Library, Heritage Images, SPL)

Greek Beards, Roman Chins

In reading the writings of the Greek historian Herodotus, one detects a hint of astonishment, perhaps even slight disdain, for Egyptian customs. “They prefer cleanliness over beauty,” he wrote, possibly alluding to beards. In Greece at that time, the beard was a defining part of a man's appearance, symbolizing strength and masculinity. A smooth face signified femininity, and in Sparta, a city that revered masculinity and military prowess, men who acted cowardly were punished by having their beards shaved.

The Romans, in contrast, often preferred a clean-shaven look. Even during the Republic, wealthy Romans typically employed live-in servants to shave their faces each morning. For those who couldn’t afford personal shavers, barbershops in Rome provided professional services from the tonsor, the Roman barber. The Romans also refined the Egyptians’ rounded razor, pioneering the development of the first straight razor.

This shaving tradition continued as the Republic transitioned into an Empire. Statues of Julius Caesar, Augustus Caesar, and many subsequent rulers depict men with smooth chins, as do statues of many other men from that era. By the end of the Republic and the beginning of the Empire, affluent Roman men rarely grew beards. However, shaving wasn’t always the method used; according to historical accounts, Julius Caesar ordered his servants to pluck his beard hairs daily, and other Romans followed suit, perhaps believing that what suited Caesar would suit them as well.

Why did the Romans insist on hair removal? Similar to the Egyptians, a smooth Roman chin symbolized high status, while a beard was associated with poverty. Additionally, some historians argue that shaved faces were meant to distinguish Romans, in their own eyes at least, as cultured people, unlike the “barbarians” outside the Empire and perhaps even the bearded Greeks.

Nonetheless, Roman attitudes toward beards shifted over time. Emperor Hadrian, who ruled in the second century CE, grew a thick beard, possibly to hide birthmarks or skin imperfections on his face. He reintroduced the beard into fashion, and subsequent emperors proudly wore beards for many generations.

Shaving one’s beard as a sign of group affiliation and a marker of distinction from outsiders wasn’t unique to the Romans. During the schism in the Christian church in the 11th century, between Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, Catholic priests shaved their beards to distinguish themselves from Orthodox Christians, as well as from “heretics” such as Muslims and Jews. In 1086, the archbishop of Rouen, France, threatened to excommunicate anyone - priests, clergy, or laypeople - who let their beards grow instead of shaving them.

5 View gallery

The bearded Greek philosopher Socrates (right), alongside the clean-shaven Roman Julius Caesar

(Photo: Shutterstock, Fernando Cortes, Wikipedia, Sting)

Beards as Signs of Mourning

In Judaism, it is customary to grow a beard as a sign of mourning, including during the Omer counting period. This practice has also been observed in various other cultures throughout history. For instance, the Romans, who typically preferred to shave their beards, would allow them to grow during periods of mourning. Augustus, for example, grew a beard following the death of Julius Caesar, and beards were also grown in response to significant disasters. Some Catholic popes also observed this custom. Julius II, who served as pope in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, grew a beard in 1511 to mourn the loss of papal control over the city of Bologna in northern Italy. Pope Clement VII followed suit in 1527 after the soldiers of Charles V, King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, captured and sacked Rome. He refrained from shaving it until his death in 1534.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

A beard among smooth chins could serve as a clear sign of a person in mourning. But what would someone do if they lived in a time and place where long beards were the norm? Often, that person would signify mourning by shaving their beard.For instance, the ancient Greeks would shave their beards as a sign of mourning. In societies where a smooth chin was considered unmanly, individuals didn’t remove it entirely but shortened it. . In ancient Israel, shaving was also associated with mourning, though perhaps not specifically the beard. In the Book of Isaiah, chapter 22, verse 12, the prophet refers to mourning practices: “to weep and to wail, to tear out your hair and put on sackcloth.” “Tear out your hair” may refer to shaving the head, which, along with sackcloth attire, was a sign of a person in mourning.

It appears that across different cultures and eras, a common rule applied: in mourning, set yourself apart from those around you by altering your beard or hair. If you usually grew it, trim or shave it; if you typically shaved, let it grow.