Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Henry Molaison suffered for many years from acute epilepsy following a bicycle accident in his childhood. Doctors identified the source of his seizures—excessive electrical activity in a specific area of his brain—and suggested surgically removing the problematic area.

Following the operation, where large parts of the medial temporal lobes on both hemispheres of his brain were removed, he indeed stopped having epileptic seizures, but he also lost the ability to form new memories. This discovery has made Molaison, who was known as Patient H.M. until his death, one of the most famous patients in brain science history and an important source of knowledge for understanding memory and the human brain.

Amnesia, the condition resulting from Molaison’s operation, is a broad term covering a range of injuries leading to temporary or permanent memory loss, stemming from physiological or psychological causes. The word "amnesia" originates from ancient Greek, combining ‘A’ (no) and ‘mnesis’ (memory). Typically, amnesia is categorized into different types based on symptoms and causes.

The injured area in Henry Molaison's brain was the medial temporal lobe, which houses an organ of paramount importance for memory formation: the hippocampus. The hippocampus is crucial for forming, storing, and retrieving memories. Following Molaison’s case, it was found that the hippocampus is responsible for our explicit memory - a memory we can describe in words.

3 View gallery

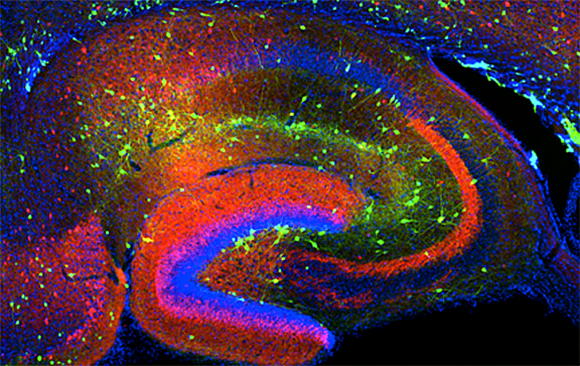

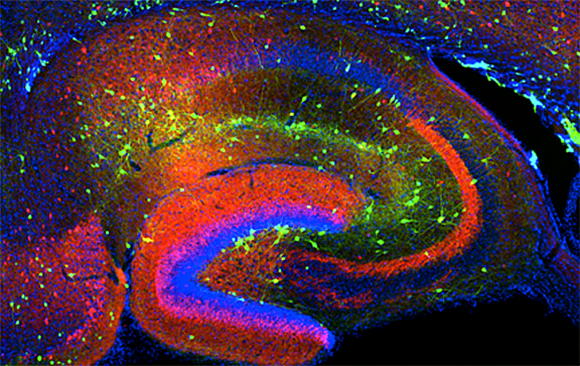

An organ of paramount importance for memory formation, storage and retrieval. A cross-section of a mouse hippocampus, where cell nuclei are stained in blue and various proteins are stained in red and green

(Photo: flickr, NICHD)

Forgetting The future

Explicit memories can be categorized into two types: semantic and episodic. Semantic memory retains factual information that we acquire throughout life, such as knowing that it is warm during summer and cold during winter. In contrast, episodic memory encompasses memories of specific experiences, like the occasion when we savored ice cream on the boardwalk.

Every time we form such an episodic memory, information from our senses is processed by the hippocampus, forging new connections between cells that represent the memory. For instance, recalling that boardwalk outing - do we recall what flavor was the ice cream? What color were the skies? What music was playing?

Amnesia resulting from brain damage, whether due to head injury, viral infection, or stroke, is termed neurological amnesia. Neurological amnesia is commonly classified into two types: anterograde and retrograde amnesia. Following the removal of his hippocampus, Molaison developed anterograde amnesia, meaning “from here onwards.” This means that while the memories from before the surgery remained intact, Henry lost the ability to form new memories.

He met his doctors daily, but they had to introduce themselves to him every day. Despite the severe impairment in his episodic memory, Molaison’s intelligence level remained unchanged, and he could recall facts about his life and engage in short conversations lasting from minutes to hours, thanks to his short-term memory, which remained unaffected. However these memories were transient and were not preserved for the long term.

The other type of neurological amnesia is retrograde amnesia, deriving from the Latin “retro”, meaning “from here backward.” This condition is characterized by the loss of memory of some or all of the events that preceded the damage, while the ability to form new memories remains intact. While retrograde amnesia doesn't typically affect intelligence or identity, patients may struggle to recognize friends and family members and may lose details about their lives - some or all, depending on the severity of the damage.

3 View gallery

Episodic memory encompasses memories of specific experiences, like the time spent enjoying ice cream on the boardwalk. A photo album

(Photo: Shutterstock, GoodStudio)

Both anterograde and retrograde amnesia likely stem from damage to distinct yet closely located areas in the brain - the hippocampus and its vicinity. Consequently, patients may sometimes experience both types of amnesia concurrently. Researchers have long sought to determine which hippocampal injuries lead to each type of amnesia. It is becoming increasingly evident that while the hippocampus is responsible for memory formation, it doesn't play a primary role in long-term memory storage.

Rather, the information is temporarily stored in the hippocampus before being transferred to "long-term storage" elsewhere in the brain. Thus, the older the memory, the less likely it is to be susceptible to damage following injury to the hippocampus or its adjacent regions. A 2021 study suggests that anterograde amnesia, the type Molaison had, may result from damage to the fornix, a region near the hippocampus, responsible for transferring information onward and related to memory retrieval.

Research over many years has shown that the hippocampus is one of the only areas in the brain that continues to produce new cells throughout life and that these may be responsible for forming new memories. Evidence of nerve cell regeneration in adult animals, including rats, mice, and songbirds challenges the historical hypothesis that all nerve cells in the adult brain were produced during fetal development and early childhood.

Evidence currently continues to accumulate that the adult human brain does produce new nerve cells, and experiments in animals demonstrate that nerve cell production facilitates learning and memory formation. Additionally, reduced cell production has been observed in Alzheimer’s patients, suggesting a link between nerve cell generation and memory. According to the hypothesis, disruption of the production of new nerve cells in the hippocampus may prevent the ability to retrieve newly formed memories and lead to anterograde amnesia.

Amnesia isn't solely attributable to hippocampal damage; various phenomena can lead to similar symptoms. Dissociative amnesia, for instance, is caused by psychological factors, such as childhood trauma, and it is characterized by the loss of memories of significant events and their details.

There's considerable variability among individuals experiencing this type of amnesia, with some forgetting specific events lasting hours or days, while others, in rare cases, may forget their entire life. There is no knowledge of physiological damage associated with this disorder, and therefore treatment typically involves psychological intervention.

Unlike long-term amnesia, transient global amnesia is a temporary condition characterized by sudden impairment of new memory formation for a few hours to a day. Patients may be brought to the hospital by loved ones, unable to comprehend their surroundings and repeatedly asking for the time or how they got there, as they are unable to retain information.

This type of amnesia is more prevalent in middle-aged individuals and is often caused by disrupted blood flow to the brain during a stroke. Brain imaging (MRI) of these patients often reveals damage indicating a specific stroke in the hippocampal area. Transient amnesia may also result from seizures or even migraines.

3 View gallery

Amnesia is not solely caused by hippocampal damage; other phenomena may produce similar symptoms. Illustration of forgetting

(Photo: Shutterstock, Lightspring )

Amnesia or Alzheimer's?

If someone you know has been consistently forgetting things lately, such as turning off the stove or their own birthday, should you suspect amnesia? Before considering amnesia diagnosis, it is common to first rule out degenerative diseases like dementia and Alzheimer’s. Unlike amnesia, which is often triggered by a specific event, such as an accident, disease, trauma, stroke, or surgery, degenerative diseases like dementia, and especially Alzheimer’s, develop gradually over time.

Dementia and Alzheimer’s are typical in older individuals and primarily result from by progressive damage to an increasing number of nerve cells over time. Alzheimer’s disease is linked to difficulty in breaking down the protein amyloid beta, which becomes toxic at high concentrations, leading to cell death in the brain.

While the average age for Alzheimer's diagnosis is sixty-five, certain genetic mutations can lead to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, during the fourth and fifth decades of life. In these cases, the damage also progresses gradually.

Due to the gradual nature of the progression of Alzheimer's disease, it can be difficult to assess whether a particular medication helps slow down memory loss. Researchers continue to develop new medicines, treatments, and experimental interventions in the hope of mitigating the harm caused by the disease.

As for the treatment of amnesia, in most cases, there is partial and sometimes even full recovery once the brain heals. However, in some instances, memory may never fully return, and currently, there is no treatment available for such cases. Despite the severity of the damage, people who suffer from all types of amnesia usually retain the ability to remember or learn procedural knowledge. This means they can learn new skills not reliant on explicit memory, such as sports, cooking, driving, and more, as these types of learning occur in brain areas outside the hippocampus.