Stones from the far side of the Moon

Last Friday morning China successfully launched the first space mission designed to bring back soil samples from the far side of the Moon. In 2019, China successfully landed the first spacecraft on the far side of the Moon, the only one to have landed there to date. By the end of 2020, the Chinese successfully completed an unmanned mission to bring back soil samples from the near side of the Moon. The current Chang'e-6 mission aims to combine these two achievements.

The mission includes four main components: an orbiter entering orbit around the Moon; a lander touching down on the surface, equipped with a scoop and a drill for collecting soil samples; a spacecraft taking off from the Moon with the sample collection container, docking with the orbiter to bring it back to Earth; and the service module of the orbiter, containing the sample container, which will re-enter Earth’s atmosphere and be retrieved upon landing.

The entire mission is expected to span 53 days and aims to bring back approximately two kilograms of soil and rocks from Apollo Basin—a crater about 500 kilometers in diameter located within the larger Aitken Basin, which spans more than 2,000 kilometers in diameter, on the southern far side of the Moon, a region perpetually hidden from Earth's view. Researchers hope the samples will shed light on the geological differences between the two sides of the Moon, enhancing our understanding of our neighbor’s geological history and formation. This mission also marks a step toward China's goal of landing humans on the Moon and eventually establishing a manned lunar base there.

The combined spacecraft, weighing over eight tons, was launched by a Long March 5 rocket from the Wenchang Space Center on Hainan Island in the south of China. It also includes collaborations with several countries: French and Swedish scientific instruments for studying gas ions near the lunar surface, an Italian laser reflector for measuring distances, and a tiny Pakistani satellite that will be released from the orbiter and also enter orbit around the Moon. Since there is no possibility of direct communication with Earth from the far side of the Moon, the mission will be assisted by a relay satellite, Queqiao-2, launched by China about a month and a half ago.

Video on the Chang'e-6 mission and its objectives:

Charting The Moon

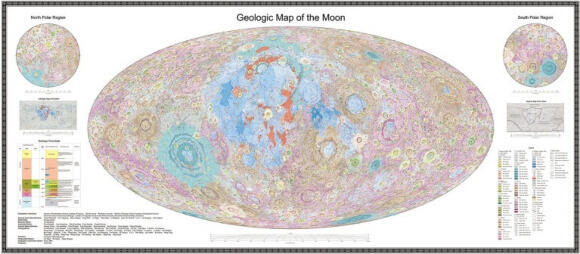

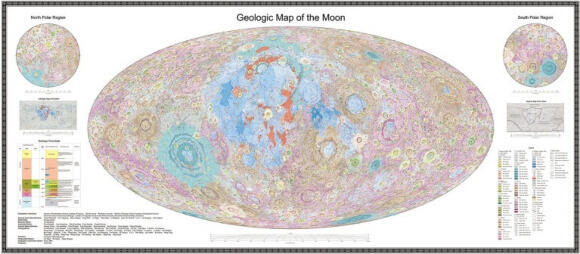

Independently of the Chang'e-6 mission, researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) have recently published the most detailed lunar atlas to date. The atlas includes lunar maps on a scale of 1:2,500,000, detailing the existing information on the geology of each area, including the types and distributions of minerals and rocks. In total, the atlas charts 12,341 craters and 81 basins.

According to the Chinese Academy, work on the new atlas took about a decade, and involved the collaboration of over a hundred researchers. It draws upon data gathered from Chinese lunar missions and satellite observations, supplemented with insights from other lunar missions.

“The US Geological Survey used data from the Apollo missions to create a number of geological maps of the Moon, including a global map at the scale of 1:5,000,000 and some regional, higher-accuracy ones near the landing sites,” said Jianzhong Liu, a geochemist at the CAS Institute of Geochemistry in Guiyang. “Since then, our knowledge of the Moon has advanced greatly, and those maps could no longer meet the needs for future lunar research and exploration.”

The new maps are intended to aid China with planning and executing its future space missions, while also solidifying its position as a leader in the fields of space and scientific research, that other countries rely upon in order to advance their own space exploration plans.

3 View gallery

Detailed mapping of more than 12,000 craters, categorized by rock types, among other features. A global geological map of the Moon, from the newly released Chinese atlas

(Photo: Chinese Academy of Science)

Sailwatch

A satellite designed by NASA to test technologies for space sail flight has established proper contact with the control center at Santa Clara University, where it was developed. The satellite is now undergoing tests in preparation for deploying its sail.

A space sail utilizes the energy of light particles, photons, emitted by the sun. Although photons have no mass, they do have energy, translated into linear momentum. Consequently, they impart pressure upon encounters with other particles. While this pressure is very small and insignificant compared to forces encountered on Earth, if a large enough sail is deployed in space, it can accumulate enough pressure to provide substantial thrust to the sail and the spacecraft attached to it.

The more light the sail reflects, the more energy it absorbs from sunlight and the more thrust it generates. This concept was tested several times in the past, and in 2019, the first sail spacecraft was launched into Earth orbit. Using solar energy in order to fly around a planet is a more complex task since the angle of the sail needs to be adjusted to maximize light absorption while moving away from the sun, and minimize it when moving towards it, to prevent radiation-induced deceleration

The new satellite, the size of a shoebox, was launched two weeks ago by Rocket Lab from New Zealand and entered a sun-synchronous orbit at an altitude of about 1,000 kilometers, higher than most satellites. Orbiting in such a manner ensures it revisits the same point on Earth’s surface at the same time every few days. Due to having only one ground station for the satellite, establishing contact with it took a few days. NASA has confirmed that the satellite’s systems are operational, and testing has begun.

Following these tests, scheduled over the next month or two, the satellite will proceed to deploy its sail. Deployment of the sail, considering the absence of wind in space, constitutes the most complex part of such missions. In the case of this satellite, ACS3, deployment will be facilitated by extending telescopic rods presently stowed within it. Once unfurled, the sail forms a square with each side measuring approximately nine meters. The ongoing experiment aims to evaluate new materials for the sail and its arms, as well as deployment technologies, with the objective of enhancing the utilization of space sails in suitable future missions.

3 View gallery

Exploring new technologies. An illustration of the ACS3 satellite after deployment of the sail

(Photo: NASA)

Communications revolution

A landmark deal between satellite communication companies may reshape the landscape of the industry, which is now facing increasing competition from emerging technologies. Luxembourg-based company SES is in the process of acquiring one of its major rivals, the American-Luxembourgish Intelsat, in a deal expected to reach $3.1 billion. Post-acquisition, the combined entity will control over a hundred geostationary communication satellites, positioned directly above a specific point on Earth, in addition to several dozen satellites in medium Earth orbit.

The field of large communication satellites stationed in geostationary orbit was until recent years one of the most profitable in the space sector, due to revenues from television broadcasting networks, internet service providers, and other entities. However, this sector now is facing intensifying competition from below: companies deploying relatively small communication satellites in low Earth orbit, notably SpaceX's Starlink network. Starlink has already deployed thousands of satellites and recently reported that it is approaching three million subscribers for its internet services.

“[This deal is] about optimizing the future of multi-orbit satellite investments and fleets,” said SES CEO, Adeeb Al-Saleh. “We just don’t need to spend as much money as we were spending separately. The combination will give us the opportunity to reduce that.”

3 View gallery

Now in control of over a hundred geostationary communication satellites. Satellite dishes of SES

(Photo: SES)