An experimental system developed by the Israeli company SpacePharma was launched on Friday to the International Space Station (ISS). Following integration by astronauts into the station's electrical and communication infrastructure, operations will be conducted remotely from SpacePharma's Herzliya-based operations center.

The system's primary goal is to conduct 19 experiments on behalf of a major pharmaceutical company, aiming to test the production of medical substances under microgravity conditions. It is known that proteins and various substances adopt slightly altered spatial configurations in zero-gravity conditions, impacting their medical effectiveness and application.

4 View gallery

A pharmaceutical laboratory capable of processing millions of droplets simultaneously. SpacePharma's experimental system in its final tests, before being dispatched to space

(Photo: SpacePharma)

Among the products included in the current experiment is an antibody already utilized in cancer treatment. The space-optimized version is expected to be more stable, facilitating subcutaneous injection without the need for intravenous infusion. In an interview with the Davidson Institute website, Yossi Yamin, founder of SpacePharma and CEO of its development center in Israel, highlighted the significance of deriving such a version of the antibody: "The implication is that the patient can receive the treatment once every six weeks instead of every two weeks, eliminating the need for hospitalization for each treatment."

The SpacePharma experiment system was launched aboard a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft, as part of an unmanned resupply mission to the ISS. It is expected to return to Earth in about a month. This venture marks the company's tenth space mission, despite only employing 12 individuals in Israel, while also operating in the United States, Switzerland, the UK, and France. The company has raised 13 million dollars in funding and approximately 8 million dollars in grants, including support from the Israeli Space Agency. The firm is on the verge of completing another fundraising round aiming for 15 million dollars. "We're also in pursuit of a strategic partner within the pharma sector, not only to manufacture drugs in space for other clients but to develop our own pharmaceutical solutions," Yamin added.

The company's system is a compact metal box, smaller than an average shoebox, packed with hundreds of meters of thin tubing and intricate mechanisms designed for liquid propulsion in a microgravity environment. "Due to the peculiar behavior of fluids in such conditions, operations must be conducted at the droplet scale,” explains Yamin. "This isn't a matter of simply scaling up a process proven at microliter volumes to a liter-scale operation; it's not feasible in space. We approach it in terms of droplets, analogous to how computers handle bits. Thanks to our developed capabilities, we can now manipulate tens of millions of droplets, both serially and in parallel."

The current experimental system is primarily research-oriented, with its output being about one gram of the pharmaceutical product. "But in a similarly sized production-oriented system we could achieve a working volume of more than a liter, yielding 100-200 grams of the product, and manage to send ten such systems concurrently. With a drug costing $4,000 per dose, we have production capabilities of tens of millions of dollars," Yamin elaborated.

In addition to experiments on the International Space Station, SpacePharma has also launched several small satellites equipped with automated research laboratories. The company is actively working to acquire the capability to land such satellites back on Earth, as does their American competitor, Varda. Concurrently, discussions are ongoing with space firms with space companies regarding the potential future deployment of private space stations and space planes for extended missions, such as the Dream Chaser.

"One of our objectives is to evolve into a pharmaceutical company that oversees drug development from inception to production," Yamin concluded. "We’ve already secured patents for two drugs that we can manufacture in microgravity, though they have yet to undergo trials. While this venture demands substantial investment and patience, the potential rewards align with the scale of commitment."

Building Blocks of Life on Asteroid Bennu

Approximately six months following the arrival of the sample collected by NASA from asteroid Bennu on Earth, and about two months after researchers finally managed to open the main sample container, the wait has proven worthwhile. The asteroid harbors an abundance of surprising materials, particularly those suggesting the existence of a watery environment in which the space rock originated. The sample contained 121.6 grams of stones and dust, including significant amounts of glycine, the simplest amino acid (NH2-CH2-COOH), which is a fundamental building block for proteins. Additionally, the sample contains minerals formed in a watery environment, such as phyllosilicates, and minerals that are typically associated with water molecules in many meteorites, including carbonates (compounds containing the CO3 chemical group), sulfates (SO3), olivine, and magnetite. Surprisingly, the sample also contains a substantial amount of whitlockite (Mg3(PO4)2) – a mineral prevalent in bones and plant material but seldom found in meteorites due to its fragility and susceptibility to breakdown

Most findings regarding the asteroid's composition are consistent with estimates based on remote analyses of its chemical composition, using instruments aboard the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft. "We got it right with the remote sensing," said geologist Harold Connolly from Rowan University in New Jersey, "and that feeds directly into how we are analyzing the sample and testing our hypotheses."

4 View gallery

Traces of a watery history. The sample capsule immediately after landing in the Utah desert in September 2023

(Photo: NASA/Keegan Barber)

Researchers hope that a detailed examination of the materials composing the asteroid and their interrelations will enable them to unravel Bennu’s geological history. According to prevailing hypotheses, Bennu broke off from a larger asteroid roughly between two billion and 700 million years ago. "We're still in the very early days of this very meticulous work. There's a lot we don't know," said Tim McCoy, curator of meteorites at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C, who forms part of the team analyzing a part of the asteroid

The Moon is Getting Warmer

China launched a satellite to the moon this week, intended to serve as a relay station for spacecraft operating around or landing on it. The satellite, Queqiao-2, was launched last Tuesday aboard a Long March 8 rocket from the Wenchang Space Launch Center on Hainan Island.

It is expected to enter a relatively high elliptical orbit around the moon, allowing it to assist in transmitting communications for missions targeting both the moon's south pole and its far side. One such mission is the forthcoming Chang'e 6 mission, where China will attempt to land a sample collection mission on the far side of the moon for the first time and return the samples to Earth.

A few days before that, China launched two spacecraft to the moon for undisclosed purposes. Details about this mission were only published after it became evident that the spacecraft, DRO-A and DRO-B, failed to achieve their intended orbits.

4 View gallery

The Red Moon program raises concerns in the United States. Long March 8 rocket with the Queqiao 2 satellite on its launch pad in Wenchang

(Photo: Huang Guochang/Xinhua)

This mysterious mission adds to American concerns regarding China's space program, including its lunar initiatives, which may potentially have offensive components. “These are terrestrial conflicts that we hope we can deter and we also don't want them, although it's more and more likely, [to] extend into space or even start in space,” said Brigadier General Anthony Mastalir, commander of U.S. Space Forces Indo-Pacific.

Icy Challenges for Euclid Space Telescope

The European Space Agency's Euclid space telescope, launched last year to try to unravel the mysteries of dark matter and dark energy, encountered an unexpected obstacle in the form of ice accumulation on one of its optical components.

The European Space Agency (ESA) disclosed that a small amount of water vapor absorbed from the air during the telescope's assembly was released into the vacuum of space, where it condensed and froze precisely on one of the telescope's mirror components. While this layer of ice is likely less than a thousandth of a millimeter thick, it is enough to affect the quality of the imaging.

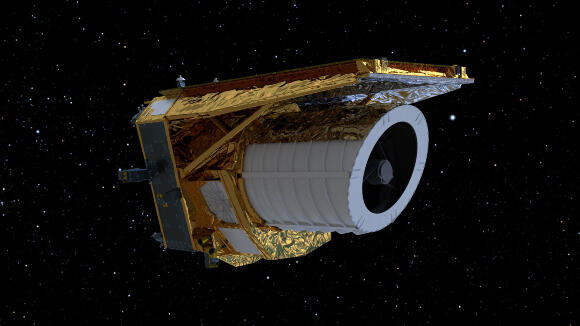

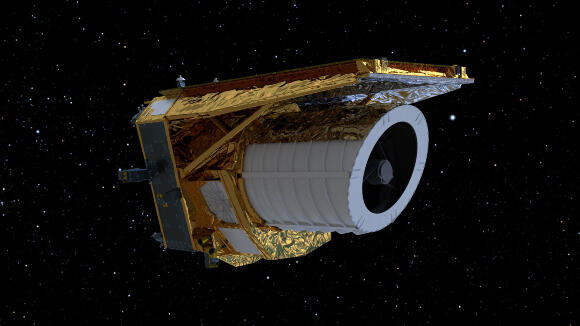

4 View gallery

From searching for dark matter to returning to the ice age. The European Space Agency's Euclid space telescope

(Illustration: ESA)

The issue was discovered after operators of the space telescope noticed a decrease in the light intensity of specific stars that had been previously imaged by the telescope. Ice formation on optical components is not uncommon in space telescopes, and there exist methods to address it, such as orienting the telescope towards the sun for a period.

The European agency has been trying for several months to devise a safe procedure that would allow the heating of the optical components without compromising their performance due to exposure to intense light and high temperatures. However, there has been no announcement regarding the timeline for implementing this procedure. Additionally, the agency anticipates that the telescope will continue to emit water vapor, necessitating periodic repetitions of the defrosting process to remove ice from the mirror