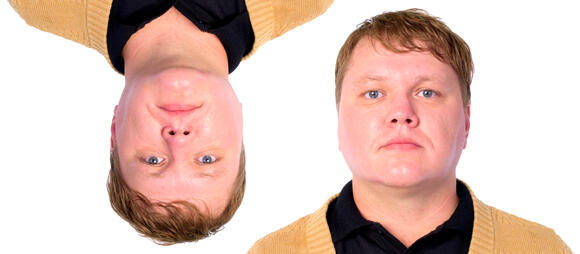

Observe the following two inverted faces. Are they identical or different?

Read more:

Can you find the differences?

At first glance, most of us do not notice any significant difference. However, when we flip them around everything becomes clear. We rapidly discover that the picture on the left is entirely normal, while in the picture on the right the eyes and mouth have been rotated 180 degrees, creating a strange and unnatural appearance.

These images are part of an experiment conducted in the 1980s by psychologist Peter Thompson from the University of York in England. In his study, he sought to understand whether our difficulty in identifying inverted faces stems from the fact that changing the orientation of the picture makes it difficult to interpret facial expressions, or whether it is related to the fact that most of the information about faces is concentrated in the parts of the face that express emotion, such as the eyes and mouth.

For this purpose, Thompson used a picture of then-British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, one of the most recognizable personalities in the kingdom, and examined how inverting the face affects our perception. He discovered that when we see a face presented upside-down, it is difficult for us to notice that parts of it have been flipped. In contrast, when we view the picture the right way up, the changes in specific organs are immediately noticeable to us.

Other animals, including tortoises and sheep, also recognize faces. Surprisingly, it turns out that the Thatcher Effect is not exclusive to humans. When monkeys were presented with inverted pictures of other monkeys, they showed little interest. Even inverted, altered images of monkeys, akin to the Thatcher images, did not attract their attention. However, when the processed images were shown in their correct orientation, the monkeys displayed prolonged interest and heightened excitement.

The reason for the Thatcher Effect is that facial recognition in our brain is a holistic process, that is, the brain searches for the familiar pattern of a face rather than processes each part of the face separately. Several regions in the brain are involved in facial recognition: the primary visual cortex is the region in which recognition of edges and angles of lines and shapes takes place. In the next stage, a region of the lateral lobe, which specializes in facial recognition, identifies the features that we look for in a face, such as the eyes, nose and mouth, and other regions of the brain collaborate in the processing of this information.

At the end of the process, we obtain a holistic, mental representation of the entire face. Therefore, makeup or a haircut change will usually not affect our ability to recognize the person in front of us, since we recognize the complete set of features on their face. This overall representation allows us to recognize faces and distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar faces rapidly and easily. In fact, humans are so skilled at recognizing faces that they keep recognizing them even in the absence of an actual face in front of them.

The Distortion That Doesn't Really Exist

In 2011 researchers in Australia accidentally discovered an additional effect stemming from human facial perception. Before we delve into this illusion, we recommend that you experience it yourselves:

Did you feel a sense of unease? Perhaps you found yourself questioning if the faces were digitally altered or Photoshopped? In reality, no manipulation was applied to the images. The flashed face distortion effect was discovered when researchers were setting up a facial recognition experiment and needed to display faces on a computer screen. To arrange the pictures in an orderly fashion, they aligned the eyes of each photographed subject at the same height on the screen, but apart from that, the images themselves were neither processed nor altered in any way.

In the experiment itself, each image was supposed to appear on the screen for several seconds, but beforehand, during the setup phase, the researchers projected the alternating images on the screen at a fast pace, just to ensure that the experiment was working properly. To their surprise, they perceived the faces as distorted, with certain facial features appearing exaggerated or caricature-like - excessively large or inflated. However, upon examining each photo individually, the faces looked entirely normal.

This phenomenon is rooted in relational encoding. Since all the faces in the database were aligned at eye level, viewers’ brains instinctively and involuntarily compared the size and position of facial features across the different images. Consequently, when the pictures alternate rapidly, differences in the structure and size of certain facial features, such as the eyes or the forehead, become noticeable. In the subsequent image, these features can appear distorted, either oversized or undersized. Modifying the speed of the image alternation or changing the spatial layout of the faces, so they do not appear in precisely the same position, eliminates this effect.

The Fat Face Illusion

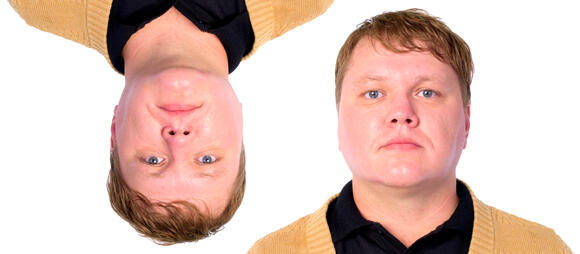

In another study, Peter Thompson, known to us from the Thatcher Effect, presented subjects with two images of the same face, one upright, and the other inverted 180 degrees. No modifications were made to the images themselves. He found that the participants perceived the person in the inverted image as being thinner or as having a thinner or narrower face compared to the same person in the upright image.

3 View gallery

Which face looks thinner? Images of the same person, upright and inverted

(Photo: Shutterstock, Ranta Images)

Subsequently, researchers from Canada, China and France discovered that when two pictures of the exact same face were displayed one above the other, viewers often perceived the lower face as being fatter compared to the upper one... Rotating one of the images by 180 degrees eliminated this illusion. To explore if this effect applied to other objects, suggesting that the lower item generally appears wider than the upper one, the experiment was repeated using watches. Interestingly, participants noted the “fatter” or “thinner” appearance only in the faces, observing no such effect with the watches. This suggests that the bias is related to our facial recognition mechanism.

Why? In the natural state, we typically encounter and process each face individually. However, when we are presented with two faces simultaneously, the mechanism of relational representation and the comparison between facial features creates the bias. When the eyes, nose and mouth are inverted, we process the relationship between them differently, resulting in the illusion that the face appears narrower.

Thus, humans possess the ability to recognize faces rapidly and with incredible accuracy. This skill develops during the first years of our lives, and is generally quite reliable, serving us well. The illusions described here arise from atypical situations that are not part of our everyday experiences, where our facial recognition abilities have evolved. These include scenarios such as displaying inverted images or showing multiple images simultaneously on a screen, which can lead to confusion. In everyday life, however, our facial recognition operates differently and effectively. Our inherent aptitude for recognizing faces is crucial, as it underpins our ability to communicate and interact socially, playing a key role in our ability to integrate and function within society.

- Dr. Adi Yaniv, Weizmann Institute of Science