Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Fossilized teeth of a tiny shrew-like mammal that lived about 73 million years ago, during one of the coldest periods on Earth, have been discovered by paleontologists in northern Alaska.

Read more:

A team of researchers, led by Dr. Jaelyn Eberle of the University of Colorado Boulder, described the creature from the Late Cretaceous period in a study published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. They named it Sikuomys mikros, a name composed of "Siku," a word in Iñupiaq (an Inuit language spoken in the northern regions of Alaska) meaning ice, and "mys" and "mikros," Greek words for mouse and small, respectively.

3 View gallery

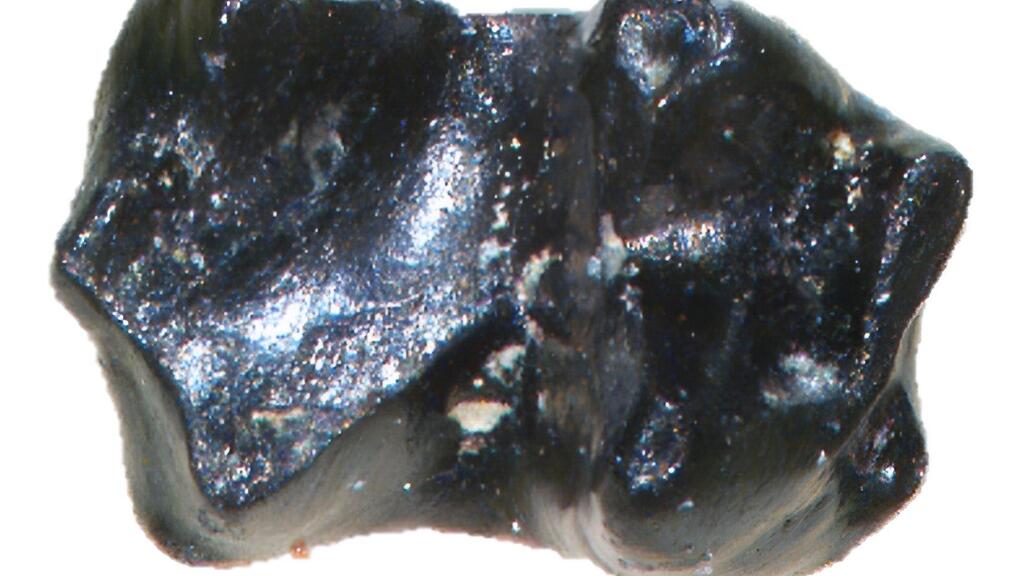

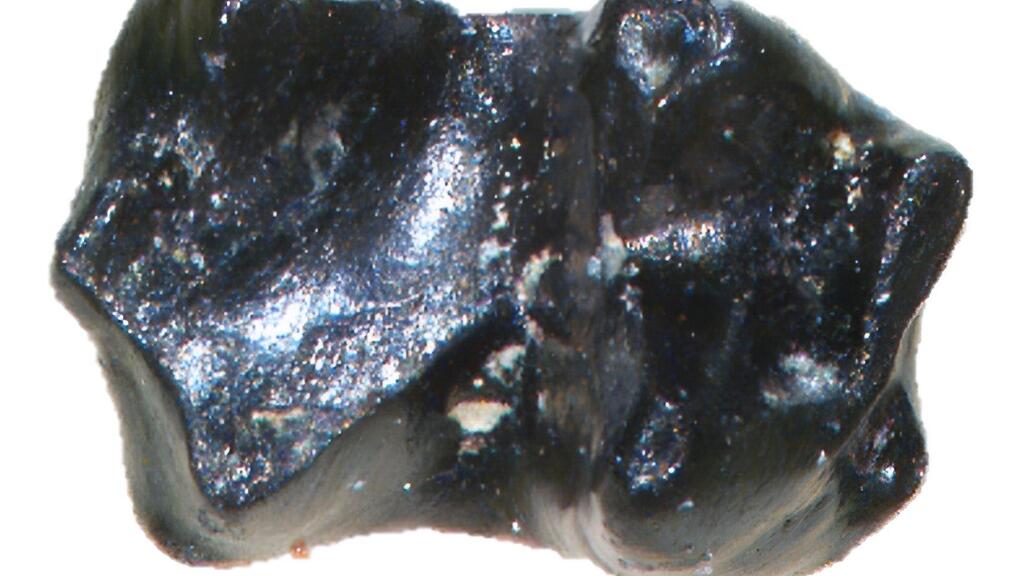

Microscopic image of a fossilized tooth of Sikuomys mikros, about the size of a grain of sand

(Photo: Jaelyn Eberle, University of Colorado at Boulder)

In fact, the "tiny ice mouse" was not a mouse at all but belonged to an extinct family of mammals called Gypsonictops. However, it was indeed tiny. The furry creature likely resembled a modern shrew, weighing in at an estimated 11 grams. It lived in northern Alaska, which at that time was located much farther north than it is today.

In that region, the tiny creature experienced up to four months of continuous darkness during the winter months and temperatures that dropped well below freezing. “S. mikros did not hibernate, but rather was active year-round, akin to extant shrews,” says Dr. Eberle.

Dr. Eberle and her colleagues identified the ancient mammal based on a handful of tiny teeth, each the size of a grain of sand. These diminutive fossils have opened a new window into ancient Alaska for the researchers.

3 View gallery

Paleontologists digging along the banks of Colville River in northern Alaska

(Photo: Kevin May)

“Seventy-three million years ago, northern Alaska was home to an ecosystem unlike any on Earth today,” he said. “It was a polar forest teeming with dinosaurs, small mammals and birds. These animals were adapted to exist in a highly seasonal climate that included freezing winter conditions, likely snow and up to four months of complete winter darkness,” said study co-author Patrick Druckenmiller, director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North in Fairbanks.

The researchers, including paleontologists from the Florida State University, unearthed the fossils from sediments along the banks of the Colville River—not far from the Beaufort Sea on Alaska’s northern coast.

“Our team's research is revealing a ‘lost world’ of Arctic-adapted animals,” said Gregory Erickson, a co-author of the study at Florida State University. “Prince Creek serves as a natural test of these animal's physiology and behavior in the face of drastic seasonal climatic fluctuations.”

3 View gallery

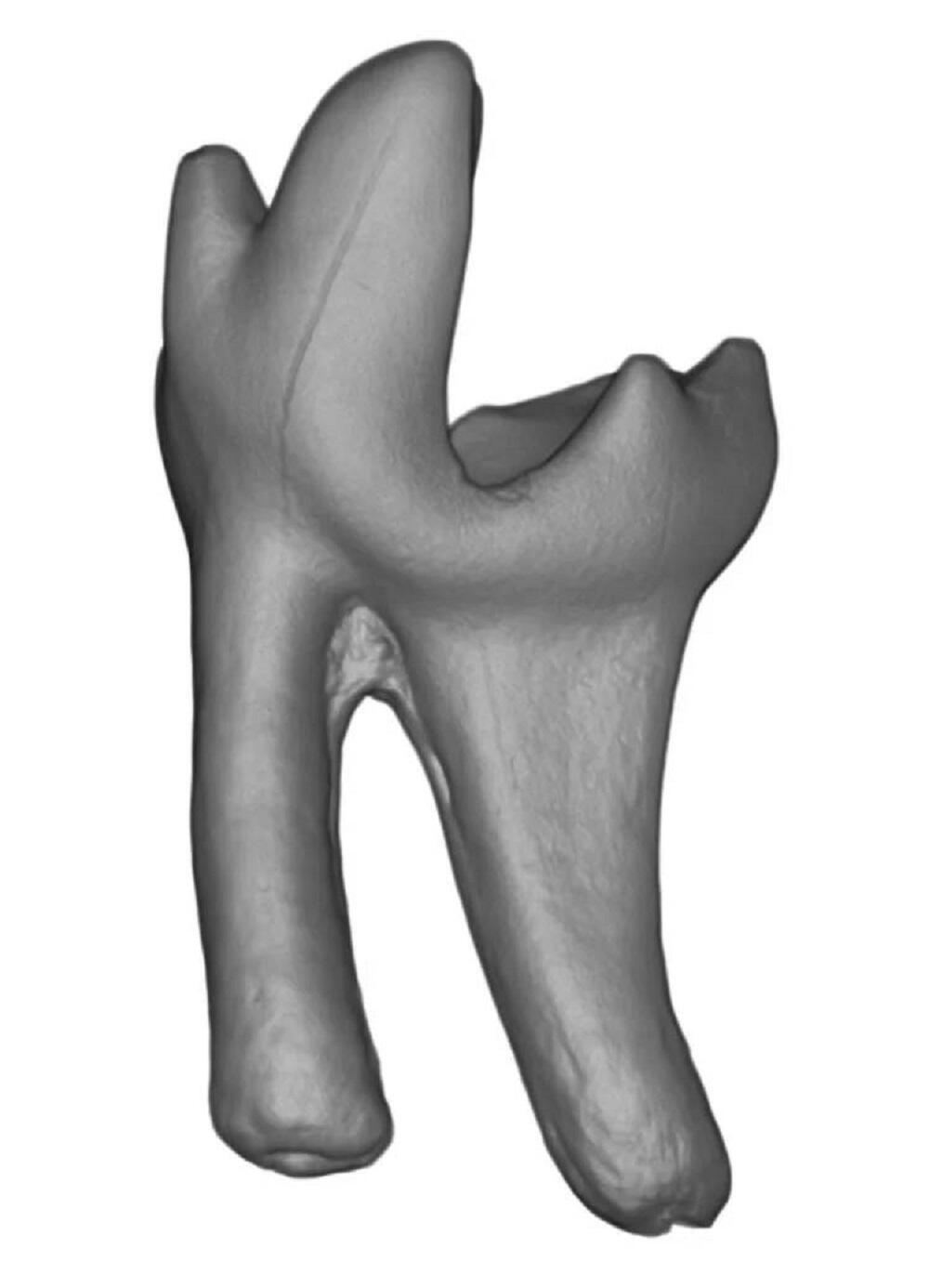

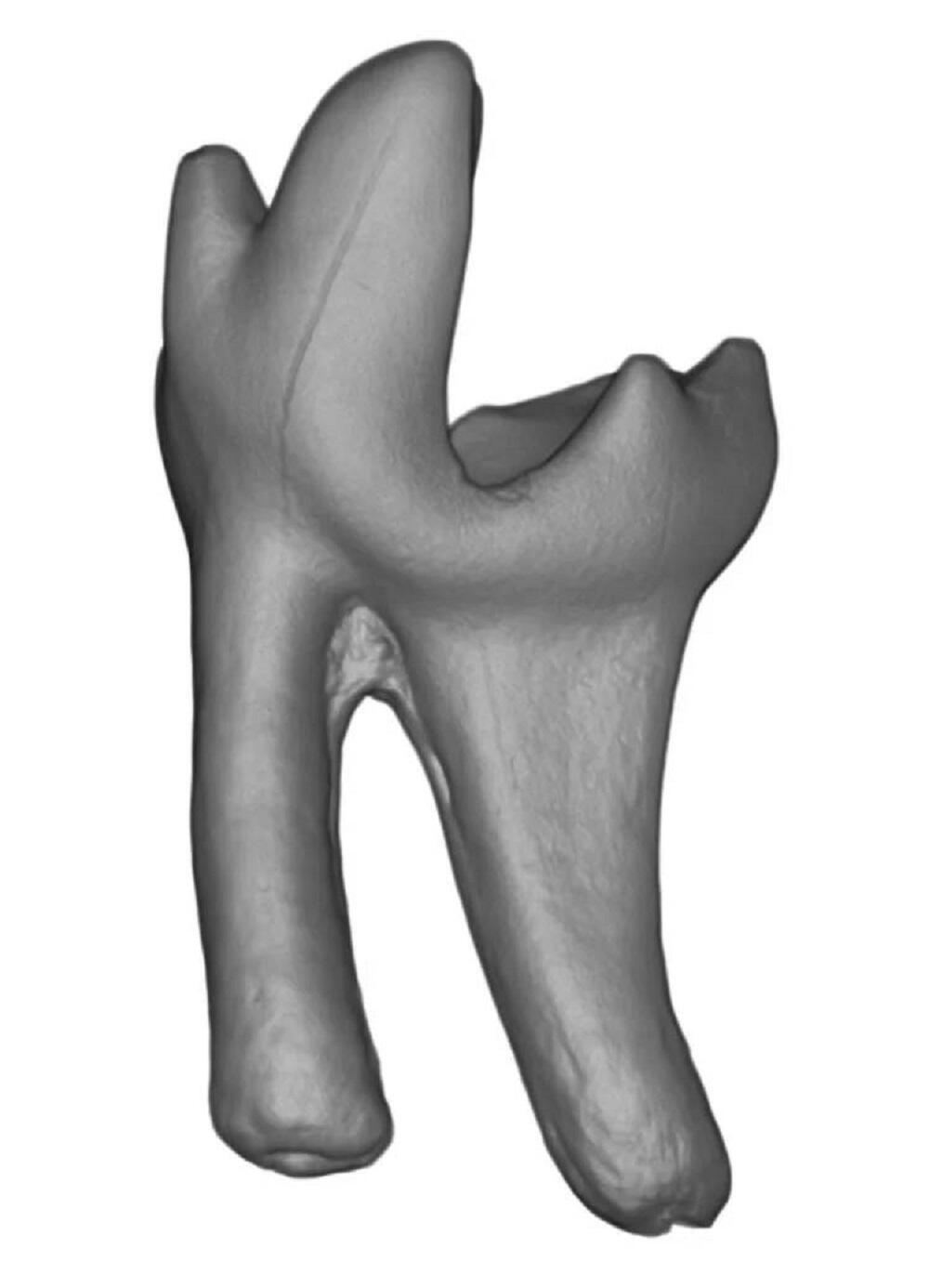

A microscope scan of a Sikuomys mikros tooth

(Illustration: University of Colorado at Boulder)

Unlike contemporary dinosaurs, which left behind large bones, the only fossils that remain from the mammals of the region are a few teeth and jaw fragments. To examine these valuable samples, researchers collected soil from riverbanks, brought the samples to the lab, and washed the mud away. They finally sorted and examined the specimens under a microscope.

For many groups of mammals around the globe, species tend to be physically larger at higher latitudes and colder climates. However, it appears that the opposite is true for this "tiny ice mouse."

Eberle suspects the ice mouse was so small because there was so little to eat during the winter in Alaska. “We see something similar in shrews today,” she said. “The idea is that if you’re really small, you have lower food and energy needs.”

Researchers speculate that Sikuomys mikros may have spent the cold months in Alaska underground. In the end, such a subterranean lifestyle may have been a blessing for animals like the ice mouse. Burrowing mammals may have stood a better chance of surviving the harsh conditions that followed the meteorite crash that killed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.