Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Paleontologists have discovered a new species of toothed whale, Olympicetus thalassodon, which lived approximately 28 million years ago, providing insights into the evolution of modern dolphins.

More stories:

This species, along with two other similar toothed whales found in the same region, belongs to the simocetidae family, which is part of the early-diverging groups of toothed whales.

Olympicetus thalassodon swam along the coast of the northern Pacific Ocean about 28 million years ago. This new species is one of several that help better understand the early history and diversity of modern dolphins, porpoises and other toothed whales.

The new species is described in a recent study published in the PeerJ journal by paleontologist Dr. Jorge Velez-Juarbe from the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

According to him, the new species and its close relatives exhibit a combination of characteristics that set them apart from any other group of toothed whales.

“Some of these characteristics, like the multi-cusped teeth, symmetric skulls and forward position of the nostrils, makes them look more like an intermediate between archaic whales and the dolphins we are more familiar with,” said Dr. Velez-Juarbe, who works as an associate curator of marine mammals at the museum.

But the Olympicetus thalassodon had company; remains of two other related toothed whales were also described in Dr. Velez-Juarbe's study.

All the specimens were collected from a geological site known as the Pysht Formation, which was exposed along the coast of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington, and is known for preserving fossils from a geological epoch called the Oligocene, dating back about 26.5-30.5 million years.

The study revealed that Olympicetus thalassodon and its close relatives belong to a family called simocetidae, a genus previously known only from the northern Pacific Ocean and one of the earliest diverging groups of toothed whales.

Members of this family were exceptional animals represented by fossils found in the Pysht Formation, such as plotopterids (an extinct group of flightless birds resembling giant penguins), desmostylia, which resembled hippopotami in appearance, and early relatives of marine predators and walruses.

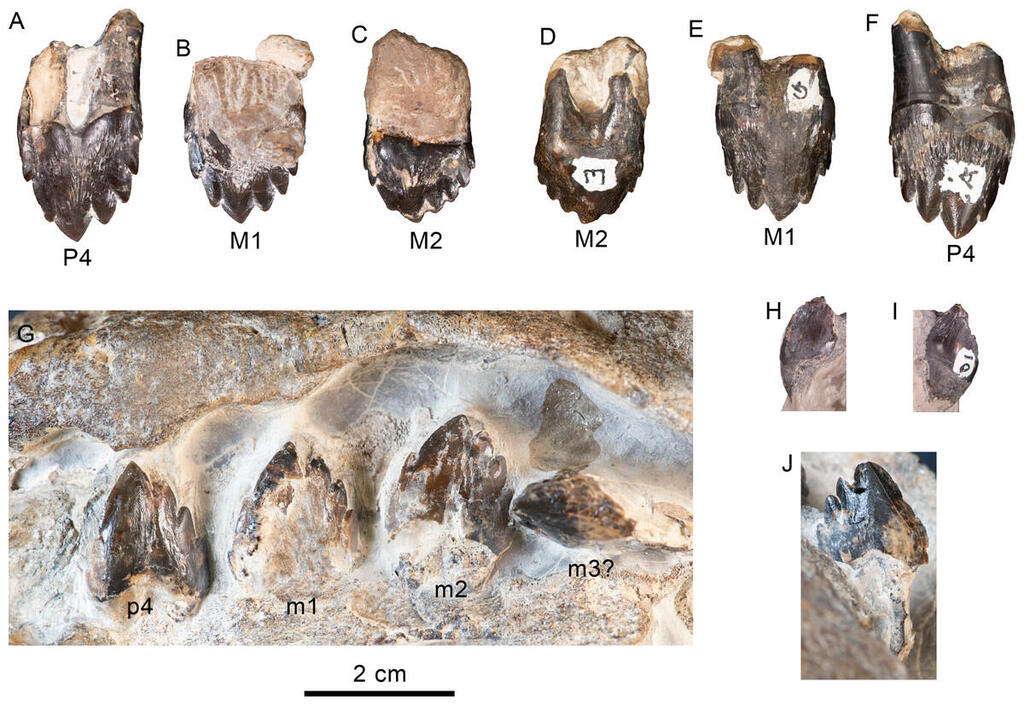

Differences in body size, teeth and other feeding-related structures indicated that members of the Simocetidae family had different feeding habits and even showed preferences for specific prey.

"The teeth of Olympicetus are truly odd, they are what we refer to as heterodont, meaning that they show differences along the toothrow,” explained Dr. Velez-Juarbe. However, other aspects of these early toothed whales’ biology still require clarification, such as whether they were capable of echolocation like their living relatives.

Most communication among toothed whales is achieved through a wide range of vocal sounds they produce, which serve for inter-individual communication, echolocation (the reflection of sound waves to map the environment), and for locating and hunting food. In fact, certain aspects of their skull may be related to the presence of structures associated with echolocation.

Previous studies have shown that juvenile toothed whales can’t hear ultrasonic sounds, therefore further studies will need to examine the ear bones of adolescent and adult individuals to see if this changes as they grow.

“The new specimens add to a growing list of Oligocene marine tetrapods from the North Pacific, further promoting faunistic comparisons across other contemporaneous and younger assemblages, that will allow for an improved understanding of the evolution of marine faunas in the region,” Dr. Velez-Juarbe said.