“I’m an alcoholic. I’m addicted to cocaine, marijuana, shopping and prescription drugs. I’m also bulimic.” This shocking confession, uttered by the actor portraying Elton John in the opening scene of “Rocketman”, is thrown out there, leaving the self-help support group dumbfounded.

More stories:

“How were you as a child?” asks the sympathetic psychologist. The next scene takes us back to Elton’s childhood when he was treated harshly by his distant parents who showed him little love or affection. However, when the singer is asked by the psychologist, about his relationship with his father, he responds: “My father was passionate about music and family and always hugged me. I was lucky to have had a very happy childhood.” In the very next scene, we see Elton as a boy asking his father for a hug, but his father ignores him and pushes him away.

This extreme dissonance is typical for people suffering from emotional detachment and indicates a repression of difficult childhood experiences – a repression that in Elton John’s case (at least according to the film on which the singer himself collaborated) led to addiction in his efforts to escape the pain he felt as a child.

In recent years, repressed memory has gained renewed interest among psychologists and psychiatrists. It means a new discovery: Repressed memory was first deciphered at the end of the 19th century by the founding father of psychoanalysis himself, Sigmund Freud.

To explain how the mechanism works, Freud compares the subconscious to a long corridor in which spirits dart about as if they were small creatures. Consciousness inhabits an adjacent room, and the creatures beg to be allowed in. Something Freud calls the “censor” stands guard between the two, and the creatures they don’t like aren’t permitted to enter the room. As the sense of “forbidden” is anxiety, these creatures differ for all of us. Sometimes a “compromise” is reached and they are allowed in, but in disguise - in dreams for example.

“Freud’s repression is a process that takes place around a variety of issues that evoke significant emotional conflict. This is especially prevalent during childhood because we are soft and find it hard to accept overwhelming and threatening situations. This mechanism actually allows us to ‘not remember’. ” explains clinical psychologist, Dr. Hadas Mor-Afek.

According to Freud, the classic manifestation of repression is the Oedipus Complex – a situation where an infant wants to be the only object of his mother’s love. His mother’s expression of affection toward her partner, the infant’s father, causes the infant a deep desire to “get rid” of him. These impossible circumstances create a situation whereby, on the one hand, the infant is attached to his father while, on the other, he views him as an adversary.

Freud found that this mechanism allows for alleviating the fear by a series of temporary measures that help the infant deal with this very difficult condition – like falling in love with a kindergarten classmate or, later in life, marrying someone who reminds them of one of their parents.

“It’s important to note that the first conflict between needs is not alleviated by the repression mechanism, and the child’s needs do not receive an appropriate response – despite the partial solutions we use to lead successful lives” Mor-Afek explains.

There are situations for which, no matter how much we bang our heads against the wall, there is no solution. These situations will only weigh heavy on our consciousness to the point that we are unable to function. So, the brain has developed an automation mechanism to help us find solutions to our problems. The problem is that, in cases that have no solution such as the Oedipus Complex, the solutions are only partial and their sources are repressed – like forgetting we were in love with our mother and wanted to murder our father. So we become competitive like our mother so as to find a partner like our father.

This partial solution isn’t bad. The problem is when we start using it – or any other partial solution. Every time we come up against a situation that reminds us of the original conflict – something that does not allow us to fully meet our needs. Despite repressing these situations, they can receive fuller and more satisfying responses once they are adults.

We all suppress incidents, thoughts and feelings that evoke anxiety. So much so that our brain prefers storing them away in a place that is safely locked. Freud believes that this isn’t such a bad solution. In his writings, he emphasizes the importance of the repression mechanism in that it allows people to live alongside one another in a civilized manner.

Freud views the repression mechanism that aims to distance man from his impulses to kill, exploit and commit acts of violence because he’s unaware of them, thus enabling people alongside one another in some kind of controlled society.

Dr. Mor-Afek, the repression mechanism doesn’t sound so bad

“Assuming you had a generally good childhood and you weren’t exposed to situations where you had conflicts with yourself. In these cases, it is indeed an efficient and functional mechanism. The problem begins when there are more and more threatening aspects, and they take up more mental functions, like thoughts, feelings and even experiences - just to conceal the overwhelming information. People then develop various symptoms that negatively impact daily behavior. Furthermore, there’s an ongoing investment of energy, forever trying to keep the conflict memory beneath the surface – and it can be exhausting. “

What symptoms can arise?

“Let’s say I was raised with very dominant parents who took up a lot of space in my childhood. I’m likely to find myself threatened or overwhelmed (leading us to what psychologists refer to as ‘emotional overwhelm’). So, I’ll repress all sorts of early life situations when I found myself afraid of my parents being angry with me and making me feel incapable, restricted or damaged. In trying to deal with such situations, I may find all kinds of partial solutions rooted in the repression, like becoming a people-pleaser or identifying with strong, controlling people. Over the years, this might lead to a place where I don’t dare speak my mind, and may find it hard to find my place in the world.”

Most of us use the term “repression” whenever we encounter an event we’d rather forget. This is invariably incorrect. “There are at least three mechanisms that look a lot like repression and are misidentified by the general public - when they actually refer to different mechanisms altogether” explains Mor-Afek.

“As we’ve said, the first mechanism is repression. The second mechanism is disassociation, also known as detachment. This is a whole field deeply connected to trauma. We all use it to some degree, but unlike repression that is regarded as an effective mechanism, detachment is problematic as it appears at the stage that the experience is so overwhelming and difficult that if we were to fully experience it, we’d lose our minds. “

“The classic example is that of incest or extreme violence where the ‘self’ ceases to be present in the situation and the person isn’t actually there. In many cases (and this is probably why it’s often confused with repression), people who experience trauma, often find it hard to remember it - not only the trauma itself but even the time period in which it took place. People carry around with them parts of years that have been completely erased from their memories. So, they don’t process methods of protecting themselves from similar situations later in life.”

Can repression or detachment appear in contexts of difficult events that don’t happen specifically to us?

“Your question leads me to a further mechanism – denial, which is also sometimes confused with repression. Unlike repression, denial doesn’t make us forget events that are hard for us, but rather it simply allows us to ignore them or regard them in keeping with our worldviews. A good example is people who say that the war in Ukraine isn’t really that bad – it’s just the media telling us it is. The person knows the piece of information, but denies it’s reality.”

“That said, it’s important to note that, in a certain way, these three mechanisms are healthy: You can’t be emotionally connected all the time to the harsh things that occur around us. It would lead to emotional overwhelm. It’s important to deal with situations that make things hard for us, but we don’t need to be constantly exposed to all the horrors of the world.”

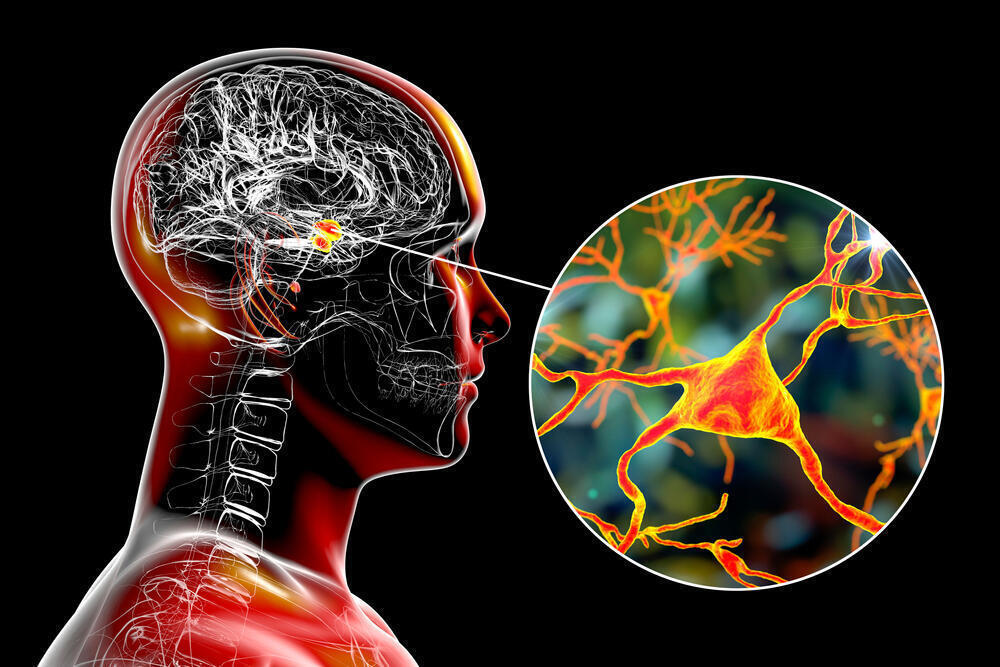

As in psychoanalysis, neurology research supports Freud and the existence of conscious and subconscious memory. Research shows two memory supersystems: Explicit memory (for which the hippocampus part of the brain is responsible); and implicit memory, including emotional memory (for which the amygdala region of the brain is responsible). A traumatic event is registered in the explicit memory, which is forever changing and focuses on the small things, whereas implicit is fixed and remembers a general impression. Despite the secure storage, the threatening feeling will likely overcome us again and again throughout our lives. “

“A person feels the same unpleasant feeling over and over because of their repeated usage of partial solutions that remind them of the repressed conflict” explains Mor-Afek. “Freud defines the condition as the ‘return of the repressed’, meaning that exposure to different situations will likely trigger an emotional or physical memory, or a situation experienced in the past that threatened us, without remembering exactly what it was. In classic psychology and psychoanalysis, we refer to it as ‘the symptom’. ”

Is it viewed positively?

“There’s something in the human ability to experience the feeling with the force it’s experienced that helps a person find a better, more effective response to their emotional needs – instead of operating a mechanism learned while experiencing those repressed events - or alternatively retreat into a state of detachment. In this way, a person can find some kind of connection to life and be much happier.”

“In therapy, both in repression and disassociation, we recommend giving space to that pain. The problem is what happens if the pain is too great to bear and it overwhelms a person? One must be careful not to cross that fine line. Our aim is not to return the trauma memory to the patients but rather to ‘cut out’ the traumatic part from their lives and provide them with the ability to bear the pain. In this way, they won’t resort to using harmful defense mechanisms that won’t allow them to deal with their problems.”

Apart from repressing unpleasant events from the past so that we can function, the repression mechanism seems to have further functions – like preventing us from recognizing the fact that one day we’ll die.

An Israeli study conducted in 2019, examining the function of the brain in repressing death, found that the human brain has a basic subconscious belief that death belongs to other people, and not to oneself. To their astonishment, the researchers discovered a part of the defense mechanism that is operated automatically whenever something reminds them of death – so subconsciously, we associate death with other people.

A study conducted by Yair Dor-Ziderman at Bar Ilan University who holds a PhD in Brain Science, examined dozens of people with a machine that maps the magnetic fields in the brain to a very high degree of accuracy and at a speed that measures fractions of seconds. Participants were asked to look at a screen onto which were projected a picture of a stranger beside random words, half of which were connected to death.

A few seconds later, a picture of the participants themselves appeared beside a word connected to death. The participants’ brain activity was constantly recorded and the researchers noted that, for pictures of strangers - both when accompanied by words connected to death and other words - certain brain activity was triggered. However, pictures of the participants themselves accompanied by words connected to death, evoked different, irregular brain activity.

“In the study, we made the participants think about their own death, to evoke what is known as ‘fear of mortality’ and record the rapid brain occurrence of encountering this thought before the repression mechanism kicks in. We proved the existence of a mechanism that neutralizes this fear the rest of the time” explains Dr. Dor-Ziderman.

It sounds like the mechanism is designed to protect us. Wouldn’t it would be very hard for us to live our lives if we were aware of death, and thought about it all the time?

“Indeed. For better or worse, depends on who you ask. Evolution has perfected repression mechanisms in our brains that allow us to live in the shadow of the impending threat of death. The moment death is comprehended, it activates an emotional detachment that makes death something that happens to other people – not to us. As far as we’re concerned, we’ll live forever. - unlike animals who, as far as we know, are not aware of the fact they will die.”

So, we actually convince ourselves we’re not going to die?

“During the study, we saw that, at a cognitive level, we know that death applies to everyone, including to ourselves. At a limbic level, however, we genuinely don’t believe we’re going to die. It may sound like somewhat satirical, but that’s how humans are built. We often identify with our thoughts and believe the stories we tell ourselves.”

On the other hand, some people live with a crippling fear of death

“Yes. People who have experienced trauma often find themselves connecting death to themselves far too aggressively. They are likely to find themselves constantly reliving that moment, and problems arise that are later very difficult to fix.”

According to the Terror Management Theory (TMT) devised by sociological psychologists, even after the encounter with death has passed, the thought of it remains with the person and evokes the need to protect themselves by connecting to something greater than themselves, such as religion or opening a doorway to harmful influences.”

“Just think about how much energy we’d free up if we made our peace with death. Most people, however, can’t accept the fact that their time will come. We’re programmed to accept death as some kind of failing or capitulation, believing that a person who has died has lost or failed, and no one wants to fail” says Dor-Ziderman.

“So, we recommend miracle cures to terminally ill patients. If they’re told they have a slight chance of recovery, but that the side effects will be horrendous, their decisions won’t be rational. Beyond all the money thrown at medication and experimentation with rather questionable degrees of effectiveness, a person in this situation will often lose their humanity as their family goes out of their mind. I look forward to the day when people accept death like they accept birth, when people stop repressing the idea of death, and accept it as a natural part of life.