The death of Mike Vigoda, the founder of the original Mike’s Place bar in downtown Jerusalem, in an alleged suicide last week highlights mental health professionals’ concern that the number of suicides in Israel has increased during the coronavirus pandemic.

While they wait for the figures to be assembled and released, a somewhat arduous process that could take months, experts are concerned that COVID-19 has led to a perfect storm of trigger points that might push people over the edge, including economic hardship and loneliness.

(Dr. Mark Weiser discusses Israel's first coronavirus ward for psychiatric patients)

“There are two good reasons why suicidality might be increased during the coronavirus, but there is no data yet. One is the social isolation … and [the other is] financial stress,” says Dr. Mark Weiser, head of the division of psychiatry at Sheba Medical Center and professor of psychiatry at Tel Aviv University.

“It is reasonable to predict [a rise in suicides], but we are only going to know after we get the hard data.”

Amid the pandemic, Israel is also in an economic crisis, with the unemployment rate hovering just above 20%.

Dr. E. David Klonsky, professor in the department of psychology at the University of British Columbia, was supposed to give the keynote lecture at the Israeli Suicide Research Symposium in May before it was postponed due to COVID-19.

“There are a lot of ways that corona can exacerbate suicide risk, like [for instance for the victims of] domestic violence, which Israel is concerned about [as there has been an uptick in abuse during the pandemic]," he says.

According to Klonsky, while the source of the pain of those considering suicide varies tremendously, outlook plays an important role in whether those who are more vulnerable to ending their lives go through with the act.

“If someone’s sense of life is extremely painful and overwhelming in a way that they lose hope that there is any way to make things better, that is what increases suicide risk,” he says.

Ruti S., a volunteer for ERAN, Israel’s emotional first aid service, who declined to give her full last name to preserve the anonymity that encourages people to contact the group’s hotline, has observed an increase in call volume.

“I have been a volunteer [for a long time] and there have definitely more calls since the pandemic started at the end of February,” she says.

Michal, who would only disclose her full name, has experienced the devastating effects COVID-19 has on mental health. Her daughter tried to kill herself by overdose in May.

“It was one of the worst days of my life. I kept calling [my daughter’s name] and she didn’t respond. I opened the door to her room and found her unresponsive on the bed,” Michal says. “I thank God every day that [the doctors] were able to save her.”

Michal’s daughter was devastated after being laid off from her job at a clothing store in Tel Aviv the day before her suicide attempt.

“I feel so guilty. I should have noticed that something was very wrong. I am her mother. Mothers should know these things,” Michal says.

“[My daughter] said that she felt useless, like a waste of space,” she says. “I never thought she would kill herself.”

However, not all mental health professionals are convinced there will be an increase in suicides during the pandemic.

Dr. Yehuda Oppenheim, one of Israel’s senior legal clinical psychiatrists, has not seen any difference in his patients as a result of the novel coronavirus.

“Corona could extenuate their pre-existing conditions because of isolation and fewer chances of meeting people,” he says.

“But I haven’t had anyone come to me as a direct result of corona and I haven’t seen in my own patients anyone who has shown suicidal tendencies because of corona.”

4 View gallery

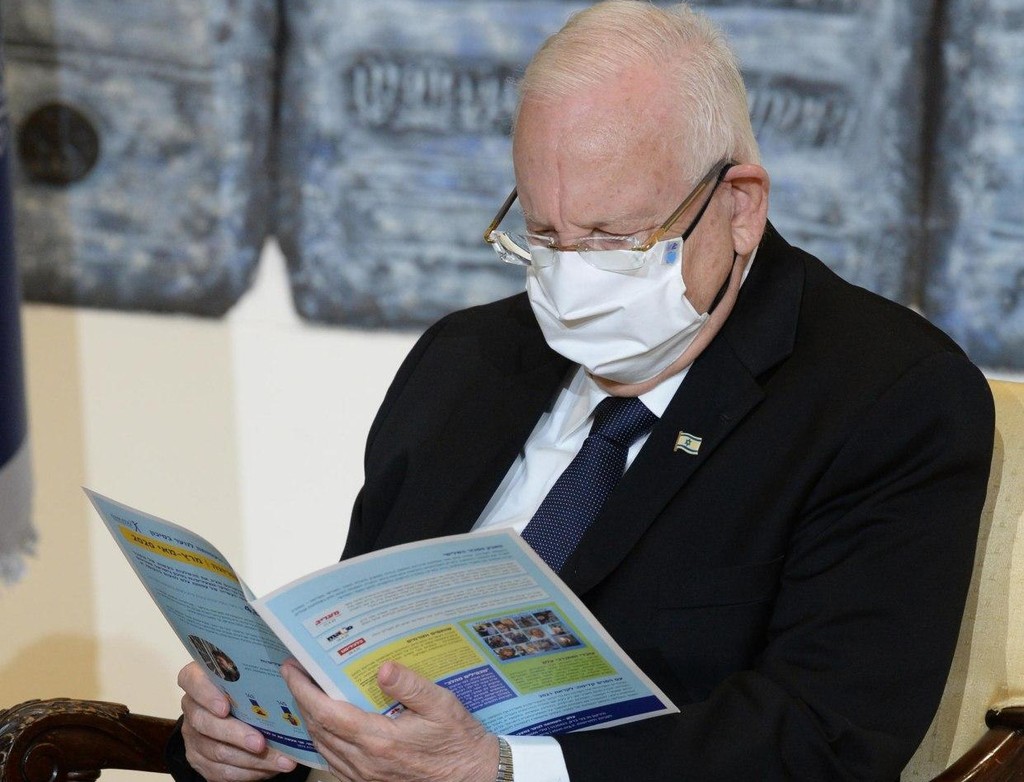

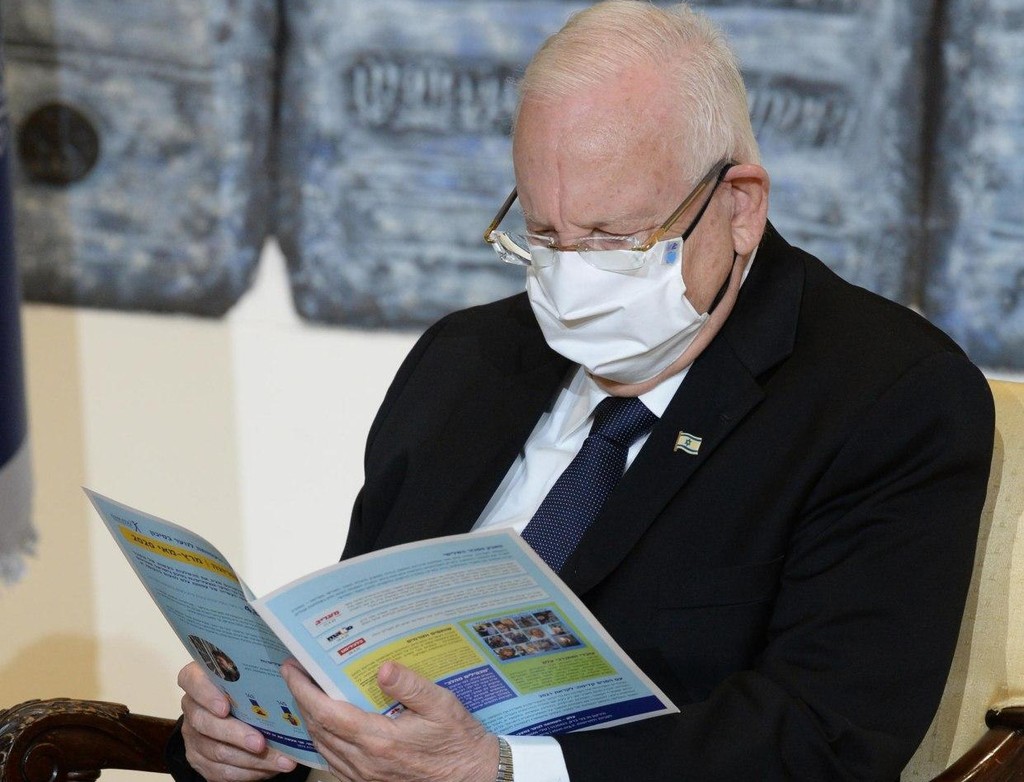

President Reuven Rivlin reads a study on young suicides in Israel produced by the Elem NGO, July 2020

(Photo: GPO)

Suicide in general has not been a rampant problem in the Jewish state.

“In the entire country of Israel, we have about 300-400 suicides a year, in a population of 9 million. Even if the rates go up to 1,200 [due to the coronavirus], this is a negligible number of cases,” Weiser says.

“The rate of suicide is low in Israel relative to other countries. Suicide is a very cultural event. In some places, like the Scandinavian countries, suicides are much higher than in other countries, like Italy and Israel, where the rate is lower,” he says.

According to Weiser, in Israel and around the world, women make more suicide attempts, while men have more completed suicides. In addition, seniors are more likely to commit suicide than young people.

He says that psychiatric conditions, including substance abuse, make people more likely to feel suicidal.

"There are things you can do to help prevent the suicide of someone you know," he says.

“More broadly, suicide is more much common in people with depression, so if you see your loved one becoming depressed, even if he or she is not directly suicidal, it is certainly something you should pay attention to and maybe even [encourage them to] see a mental health professional,” Weiser says.

“Patients with severe mental health illnesses have very high rates of suicide; somewhere between 5% and 10% of patients with schizophrenia will end their life by suicide.”

Of course, treatment for mental health is not always easy to obtain during the pandemic.

“The number of people coming into mental health clinics has gone down because people are afraid of getting corona; as a result, we are doing a lot of [telemedicine] over the phone or video. In addition, old people have almost all stopped coming in,” Weiser says.

The elderly might not be as familiar with technology as younger people, making these online visits difficult.

For people in such poor shape that they need hospitalization, getting in-patient care is also a challenge.

“At other psychiatric hospitals, the hospital directors were justifiably concerned that… one or two patients could infect an entire ward,” Weiser says.

“For that reason, many of the psychiatric hospitals are discharging patients and their occupancy levels have gone down.”

For those who are positive with COVID-19, getting treatment for mental illnesses is an even bigger obstacle.

“Because of the dangers of infection in psychiatric hospitals, we at Sheba opened up in February the first psychiatric unit in the country for all psychiatric patients who were positive for coronavirus, in order to decrease infections in [other] psychiatric hospitals,” Weiser says.

The exacerbating effects COVID-19 has on mental health have professionals in the field calling on everyone to stay vigilant to prevent suicides.