Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Wandlitz is a village in the state of Brandenburg, Germany, consisting of 25,000 inhabitants, and the kind of place that tourist guides would definitely call "picturesque". A half an hour's drive of just 22 miles north of Berlin, and you reach this marvelous place: green forests, pastoral silence and peaceful bike paths.

"Most people who live here were raised here and came back after they were through with education and career, wishing to grow old here; those who stayed in the East following German reunification, were either families who worked in Berlin but wanted a bit of quiet, or wealthy Berliners who needed a quiet place for the weekend or the summer," says Catherine Brozovsky, owner of a real estate agency located on the main street of the village.

These are exactly the reasons why Wandlitz has a dark past. Not far from here, for example, is the villa of Hermann Goering, one of the Nazi Party leaders, and nearby is the hunting lodge and bunker of Erich Honecker, the leader of East Germany and the prime organizer of the building of the infamous Berlin Wall.

But this is not why Wandlitz has made headlines in recent months. To find the reason one should drive for ten minutes, down the road that leads to the village, beside the Bogensee Lake. All of a sudden you will see an abandoned bus station, all covered in stickers and Nazi inscriptions in Gothic letters. Then you will encounter a large garage, where there used to be a fleet of black luxury cars, decorated with swastika flags, some of which were convertibles, so that he could wave to the crowds at the mass gatherings he organized.

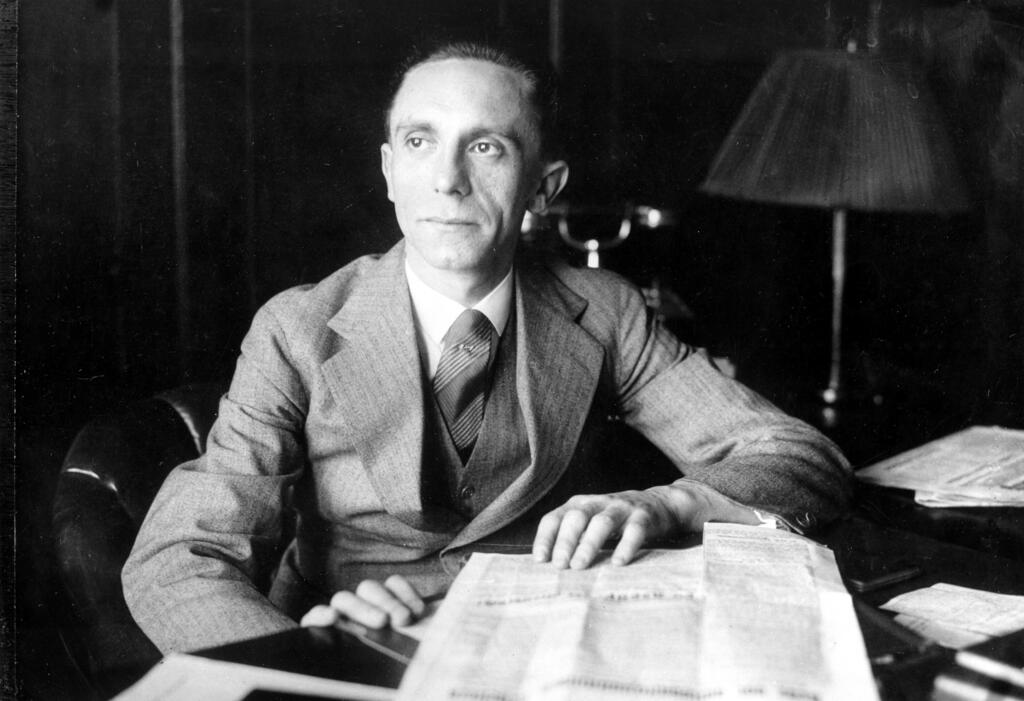

Right after, there is a building where his bodyguards were housed. And then it shows: a spacious villa, the finest architecture of the 1930s, extending over 17,000 sq ft. on one elongated level; walls that were once white, a tiled roof, and an entrance above which the inscription "Bogensee", the German name of the nearby lake, is displayed. This is the summer Villa of Josef Goebbels, the Propaganda Minister of the Third Reich and one of Hitler's closest associates.

Goebbels received the land as a gift from the state of Berlin in 1936, he had the villa built in 1939 and used it as a retreat for his personal needs. In 1943, after his home in Berlin was bombed by the Allied forces, he moved to live there with his wife Magda and their six children. They decided to move back to Berlin to Hitler's bunker in the final phase of the war. After Hitler and his new wife Eva Braun committed suicide, Goebbels managed to serve as Chancellor for one day. Then he and Magda poisoned their six children and committed suicide as well.

Meanwhile, the villa moved from one dictatorship to another. The Soviets, who controlled the territory of Wandlitz after the war, built there four huge buildings on a total area of about 40 acres. The massive complex was used as an education center, dormitories and cultural center for East German youth, so they could learn the principles of communism.

Since then, the Soviet dictatorship has also collapsed, and in the meantime, all the buildings - one Nazi villa and four Stalinist concrete monsters - have stood as monuments during almost six decades of totalitarian regimes. The ownership of the site returned to the state of Berlin. However, the city found no use for it.

In the last 25 years, the entire complex has been abandoned and neglected. In the meantime, nature is taking its own course: the beech trees grow wild, the walls are overgrown with nettles, mold and rot. The roof was leaking and had to be replaced at a cost of four million euros. Everything is crumbling, and the maintenance and upkeep costs have been borne by the public.

Last May, Berlin's new state finance minister, Stefan Evers, has had enough. Every year the state spends about a quarter of a million euros for the maintenance and security of the complex, mainly because it attracts groups of neo-Nazis. “I offer to anyone who would like to take over the site, to take it over as a gift from the state of Berlin,” stated the minister. “If we fail again, as in the past decades, Berlin has no other option but to carry out the demolition that we have already prepared for,” he added.

Then the mess started.

30 rooms, 40 study rooms and one cinema hall

It is seemingly a simple deal, offering a huge area of about 170 acres, isolated, in the middle of a green lung of trees and water, half an hour's drive from Berlin, and all for free. It should have been a gem for real estate agents. But the German authorities themselves don't really know what the purpose of this complex should be.

There are those who claim that it should be obliterated, to completely erase the past, and construct a new project instead; in contrast, there are those who are convinced that this is a historical site that must be preserved. But if so, then why give it to an entrepreneur? After all, a museum is not profitable, and besides, the renovation of the place will cost millions. Above all, there is fear that the place could attract German far-right extremists, turning it into a pilgrimage site and a shrine, worshipping Goebbels.

"The history of the place is precisely the reason why Berlin would never hand this building over to private hands where there would be a risk that it could be misused," Minister Evers warned when he announced the ultimatum.

This fear is not unfounded. Berlin tried to sell the land in the past. "The only serious inquiries were from a Russian oligarch, who wanted to establish a private education center but could not prove to the Germans the source of his money," says Claudia Schmid-Rathjen, a Wandlitz-based historian.

"An earlier inquiry, from an extreme-right group called the Reichsbürger movement, seemed to embody the authorities’ worst fears. The group denies the legitimacy of the current German state; some of its members are on trial for a plot to overthrow the government.

In Berlin, they don't know whether to repurpose or bulldoze the site to save maintenance costs. In contrast, there are historians and academics who oppose demolishing the buildings that hold German history. No one can agree what to do with a villa so tainted that no one is willing to buy, or even get for free."

But to understand how much this piece of land is charged with emotions and history, one should go back more than a century. Originally, this area belonged to a rich Jew named Friedland, from whom in 1913 the state of Berlin purchased the land. Schmid-Rathjen explains that there were two reasons involved, marking a vision of a hundred years ahead: the industrialized Berlin needed a green belt around it; Berlin's population growth will be such that it will have to find housing solutions outside the city."

But Germany sank into World War I, followed by hyperinflation and political instability. Then the Nazis rose to power. Goebbels was a high-ranking official in the Reich and played a major role in spreading Nazi propaganda using cultural and media platforms within Germany.

The state of Berlin was very impressed by his achievements and decided in 1936 to gift him the estate by the lake Bogensee. There Goebbels decided to build his dream villa. When he was not in his apartment in Berlin with his new wife Magda (the two were married in 1931), Goebbels lived in a log cabin in the compound, where he spent time with his mistress, Czech actress Lída Baarová.

Two years later, Magda found out about the affair and turned to Hitler demanding to divorce Goebbels. Unwilling to put up with a scandal involving one of his top ministers, Hitler demanded that Goebbels break off the relationship with the actress and threatened Baarová using the Gestapo. It worked, but later Goebbels had several affairs, and so did Magda.

Goebbels was very much involved in the construction of his villa. As he wanted to overshadow the villa of his neighbor Goering, Goebbels built a house with 30 rooms and 40 study rooms, clever day-room windows that fold away into the floor at the push of a button, 60 telephones, a cinema hall with 525 padded seats with preparation for headphones, wooden ceiling decorations and other architectural avant-garde and technological luxury that were popular at the time; of course, he also had a bunker. "It's so comfortable here that you can think you're living in peacetime," Goebbels said of the place in 1943.

When completed, Goebbels used the villa to entertain Nazi leaders, artists and actors. But he would also work there. Today it is impossible to enter the villa, but I did manage to have a tour from the outside and peek inside through the boards blocking the windows to two rooms: one room with a large fireplace where Goebbels sat with Albert Schaefer in 1944 planning the renovation of German cities after the war.

The second room, to the right, was Goebbels' study, overlooking the lake, where he wrote his diary and many of his speeches. Here, for example, Goebbels wrote the "Total War" speech that he delivered in February 1943.

"The villa is not his at all. It was co-funded by the UFA film company", says Peter Longerich, a historian from Munich who wrote a biography of Goebbels. Goebbels loved abundance and luxury in his private life. He would use the villa mainly to entertain friends and Nazi elite leaders. They would come to advise him on the materials he reviewed on his weekly radio show, adds Longerich.

But the luxurious life was about to end. In 1945, when it was already clear at the top of the Reich that Germany was going to lose the war, Goebbels and his neighbor chose two different paths.

"Göring ordered the killing of all the animals on his farm, so that there would be no food left for the Russians; he blew up his villa and then went to negotiate with the British," says the historian Schmid-Rathjen. "But Goebbels was an ideologist. He left the villa intact and went to Berlin, where he, his wife and their six children committed suicide in Hitler's bunker."

The villa was left intact and was used briefly as a military hospital. Very quickly it was nationalized by the East German Communist Party, becoming an education center for the party's youth organization. Here the young leaders of East Germany and the Communists in general were to be nurtured. In the mid-1950s, architect Hermann Henselmann, who designed the monstrous Karl Marx Avenue in Berlin, erected the four buildings of the school. When finished, the complex could host 800 young students from around the world, who were to get communist education there.

"I was a communist in West Germany and the organization sent me to study there between 1983-1984," says Detlef Siegfried, Associate Professor of History at the University of Copenhagen, Department of Germanic Studies, who wrote a book about the compound.

"It was an amazing experience which involved studies, conversations, activities, parties and meetings with people from all over the world. I remember it as a very secluded place, in the middle of the forest. I was very surprised by how much East Germans admired Western brands like Coca-Cola, which we despised. We, Westerners, went there as revolutionists, we wanted to replace capitalism with socialism. The East Germans went there to learn how to organize frameworks."

Did you know anything about the villa there?

"We knew nothing about the villa and its history. Everyone I talked to from that time did not know either, although it was clear that it belonged to a different era. It was very strange in retrospect, because East Germans always pointed to the West as Nazis, and the villa could have been used as a propaganda tool for them, to show the difference. But they said nothing to us."

In the early 1990s, following the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany, ownership of the site returned to the state of Berlin. In the four new buildings, dozens of listening devices are discovered, leading straight to the East German Ministry of the Interior.

Various uses were made of the structures: Deutsche Bank settled in the complex; then there was a center for training social workers. The place was revived, a hotel and restaurants were opened. Nothing worked. The property was completely abandoned about 25 years ago, and since then it has only been crumbling and costing the German taxpayer money. Lots of money.

Preserve or demolish?

Real Estate agent Catherine Brozovsky estimates that currently, the value of the property is very low, at about 600 euros per square meter, because it is abandoned and neglected, with no infrastructure, no public transportation or internet. An investor who will renovate it, can receive a value that suites an estate by a lake, which is almost 8,000 euros per square meter. Even when disregarding the areas designated for conservation and afforestation purposes, the property's worth is estimated at hundreds of millions of euros."

Renovation and repurposing the property could also cost the future investor many millions of euros. Rabbi Menachem Margolin, chairman of the European Jewish Association (EJA) has also issued an appeal to the state of Berlin with an interesting proposal to convert the mansion into a center for combatting antisemitism and hate propaganda, which are dangerous, causing even normal people to do terrible things.

And who will finance it?

"Hopefully the government and organizations that deal with Holocaust commemoration and education against hate speech and antisemitism. We are busy trying to recruit Jewish donors to increase our chances vis-a-vis the state of Berlin."

This is not the first time that a Nazi site has been converted into a memorial site. Hitler's Austrian birthplace turned into a human rights training center after it became a pilgrimage site, used as a shrine for neo-Nazis. Also, the villa in Wannsee which hosted the famous conference where the "Final Solution" was discussed, also became - after quite a few debates - one of the most famous and most visited memorials in Berlin.

"It's a big quandary for the Germans, whether to preserve or obliterate the edifices from Germany’s Nazi past and in this case also the communist regime, especially today when the extreme right in Germany is on the rise", says the historian Schmid-Rathjen.

"We need to think how many sites should be preserved, and how much we should be considerate of the municipalities' needs. Will the demolition mean the erasure of history, or are there other ways to remember the place? In Yad Vashem, there are no more victims, but they live on the internet. The truth and historical facts are already inscribed. So, I think it won't be a disaster if they obliterate the place."

Oliver Borchert, the mayor of Wandlitz, actually thinks that there should be no measures or decisions regarding demolition. "We mustn't talk about the demolition," he says, "because extreme right-wing movements might take over it, the value of the property will decrease and will not do justice to its historical importance."

So, what else can be done?

"It needs transformation. You have to find a use that can stand against and reflect the shadows of the house and its history", says Borchert. There needs to be a place that will be used for education for democracy, a research center and a campus, and the rest of the area will be left for private use such as a hotel, rehabilitation and recovery center. It is a building of historical and architectural importance, and we need to learn how to get along with history, it is impossible and forbidden to destroy history, he added.

The Berlin municipality is trying to cope with the fear that neo-Nazi organizations will take over the property; thus, it determined that the taker would have to submit an offer that would include a detailed plan for ten years, no matter what. "So, the question is what happens after ten years," says Schmid-Rathjen.

"Extreme right-wing organizations can prepare a wonderful plan, finance a shell company, and after ten years will use it for evil, turning it into an education center for extreme right-wing studies. That's why I think it's all bullshit. No one will destroy the only private house left, which is linked to the rise of the Nazis. Nothing will happen."

"This is a place of propaganda, misanthropy, distortion of words, a crime scene," says journalist Stefan Berkholz, who also wrote a biography on Goebbels. "There must be a place with a concept here, with priority for an educational institution. Demolition would be a scandal, erasing the reminder for future generations. It would become a no-man's land that would always be occupied by memories, and then the question is - who tells the memories, who controls the narrative."

What do you suggest?

"We must turn this dark historical place into a bright future that will illuminate history and warn future generations. But it seems that Berlin only wants the wild weeds to grow and hide the place and its history. We must not forget what happened here: a mechanism of two paranoid regimes. We must not allow the wild weeds to hide it."

"We can allow Elon Musk to build a Tesla University there," says Mayor Borchert, "but he will not be allowed to build a Tesla factory there, and we will not authorize any entrepreneur to build thousands of housing units there. Ideally, we would like to have an academy for democracy, a campus for sciences of resistance to dictatorships; and everything should be funded by the German government."

And the villa? Will it be demolished?

"As far as we are concerned, it will not be demolished. There are already many problems in the world that cover up the past, making it disappear over time with no ability to learn from it. And there is also the opposite scenario, in which the right-wing wins the elections and turns the place into an ideological education center."

Lost place

We are sitting in an Italian cafe on the banks of the lake. "The children of Goebbels traveled on this road to get to school, using a peasant carriage," says Schmid-Rathjen, then pointing to a nearby shop. "And here they would have an ice cream."

Also today, children eat ice cream here peacefully, families have bike rides around the lake, and the wind attracts dozens of windsurfers to the place. It is a hot summer day in the green belt around Berlin, and it seems that only a few care who lived here, in the adjacent villa.

What about the villa? Schmid-Rathjen thinks that nothing will happen at the moment. "No one has come for 25 years and there is no reason for anyone to come now. It will be a waste of time and energy. It's a lost place."

Do you have another idea?

"As a historian, I would say that this place should be given for free to Israelis who came to live in Berlin, as a sign of solidarity. Let them turn it into a culture club, have techno parties, alongside exhibitions that explain about the history of this place."

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: