Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The 47-minute "Horror Movie" of the IDF Spokesperson's Unit has become the most talked-about chilling film both in Israel and in the world, and undoubtedly the most powerful card in Israeli advocacy. Now its creators, Yuval Horowitz and Matan Harel-Fisch, are speaking out and telling which materials broke them, how they decide who will watch it, what measures are taken to prevent it from ever leaking, and how can they sleep after hundreds of hours of watching, while the soul cannot forget.

Read more:

The film 'Bearing Witness to the October 7th Massacre' known as the "Horror video of the IDF Spokesperson's Unit" is not beyond watching or any other outcry among the cries of despair uttered by Israeli government ministers who forgave themselves after a few minutes of viewing. The film can be watched, or maybe, essential to be watched.

The film is hard to watch and contains graphic footage of 139 murders in every conceivable and inconceivable or intolerable way; when watching the film, the body seems to stiffen and try to defend itself against the sights, but the trails of blood, the piled up bodies, the shooting from the shooter's point of view, are sights that you have probably seen countless times in horror films, action movies and violent video computer games. The truly incomprehensible and shocking thing is knowing that this is not only documentary, real and tangible, but rather something that occurred here, in Israel, on October 7. At home. In homes. In kibbutzim, in towns and at a party.

Not the safe haven previously believed

It happened to Israelis we know, even if not personally. Here, toddlers wearing Disney pajamas were murdered in their beds. Here, sweet children's bedrooms turned into slaughterhouses. Here, soldiers and women that have been shot, were loaded onto vans while being humiliated, disfigured, stripped of their clothes, and were taken speedily back to Gaza, to the cheers of their captors and the local crowd. Here a music festival has become a human shooting range. Here Israeli bodies were abandoned in conditions that are hard to imagine. All of these are documented in the film over extended minutes, alongside other horrors perpetrated by Hamas terrorists during the hours they moved between the southern settlements almost unhindered, while murdering, burning, raping, beheading, looting, abusing bodies, taking prisoners and above all recording themselves with body cameras.

The mind cannot and refuses to absorb the sights, and with each additional minute of the screening - during which the eyes ask for only one thing: that it will finally end – the feeling of anger, helplessness, frustration, disbelief and shock rise up. As human beings, watching the movie takes your humanity and your faith in the human race as a whole, over the edge. As Israelis, the impact is doubled.

There are things that the human mind has a hard time erasing, and the 47-minutes long "horror video" is perhaps the most indelible material that the human mind may file. When I started this article, I was not interested in watching the movie. Why assign to this terrorist cell, which perpetuated itself while carrying out what the imagination itself could not invent, even a single brain cell, which will surely burn with shock and grief. Then I realized that I would have to watch it. And I did. Perhaps because the film in the meantime has become a "brand", as defined by Yuval Horowitz, 43, one of the two creators of the film in the IDF spokesperson's unit.

Clamoring for horrors

He is right, and it is, tragically, almost obvious: the "horror video" has become a kind of hot commodity and Israel's strongest and most sought-after advocacy card at the moment. "We receive dozens of requests a day from Israel and the world to watch the film," Horowitz says, "but we guard it with reverence so that it does not leak, and we don't show it to people other than select groups who we think should watch it, such as high-profile influencers, international reporters of major media groups, foreign diplomats, ambassadors, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, security agencies. Those who are not on these lists should really not watch it, and we say a lot of 'no'." "The screening is not a sensation," adds Matan Harel-Fisch, 41, who created the film together with Horowitz. "It should serve a goal."

Indeed, the film was not created for a large audience, even though it has been watched by an ever-growing audience. So far it has been screened about 200 times and watched by over 4,700 people in more than 50 countries. Within the IDF Spokesperson's Unit, a team was established to manage the screening permissions and to make sure that the screenings are performed according to the established rules: no phones are allowed and recording devices are prohibited. The international screening team consists of military attachés and Foreign Ministry personnel who undergo briefings before each screening. The film was screened, among others, to members of the Israeli Knesset, Hollywood executives, and last week it was screened at the United Nations to a large audience who left in stunned silence. This is not uncommon: "The common denominator for all screenings is that when the film ends, there is silence, a deafening silence that seems to last forever and persists until people manage to move and stand up," Horowitz says. "Everyone is left exhausted, feeling hollow, unable to grasp that this is what happened here, and the number and types of murder. It is something that the soul cannot comprehend, the human mind cannot contain the evil and the cruelty."

The head of IDF Spokesperson's Unit, Rear Admiral Daniel Hagari, who initiated the film, describes in informal conversations its main impact as "horror and distress", especially due to the ability to witness the entire course of the Hamas attack, often from the perspective of the terrorists themselves. In fact, the "video of horrors" became something it was never intended to be - a story that no short video clip could ever convey, given the chronological sequence of the largest and most brutal massacre against Jews since the horrors of the Holocaust, and the only document capable of conveying something of the magnitude of the horror. "People are left shattered because they understand that a hate crime against humanity was committed here on a different scale," Horowitz says. "And these were our two goals," adds Harel-Fisch: "To expose this horror, and to let anyone who watches the film understand the magnitude of the crime.

"I always tell the audience at the screenings: 'We don't have these two images of September 11 - of a plane crashing into a tower and a tower that collapses - through which you immediately understand the magnitude of the event. Here the event took place in over 30 communities, across expansive terrain, and that's why, at one point, we counted the bodies of the people who were murdered as seen in the film and added a caption at the end: 'What you witnessed is less than ten percent of what happened on that same morning." That means, you finish watching those 47 minutes, you've been through an emotional upheaval, and you haven't even seen a tenth of what happened. So, making the magnitude of the crime accessible is the first thing we are trying to do, and that's the role of the human footages - seeing something is happening, seeing people's reactions, seeing children crying. Our second goal is proof: when you see a body completely burned in a certain position, there is a sense of defamiliarization; i.e., someone sees it but he does not see himself there. But this is courtroom evidence."

It is important to note: the film keeps changing, from screening to screening. I watched its 16th version. The materials continue to be collected by Horowitz and Harel-Fisch in every possible way and have already accumulated to hundreds of hours of raw footages. "I've been to all the places, in ZAKA facilities and the IDF's 'Shura' base (the facility at which the bodies of those who were murdered are housed and identified), I sit for hours every day looking for materials; I am listed on everyone's phone as 'Matan - Horrors', and they know exactly what I want," Harel- Fisch says.

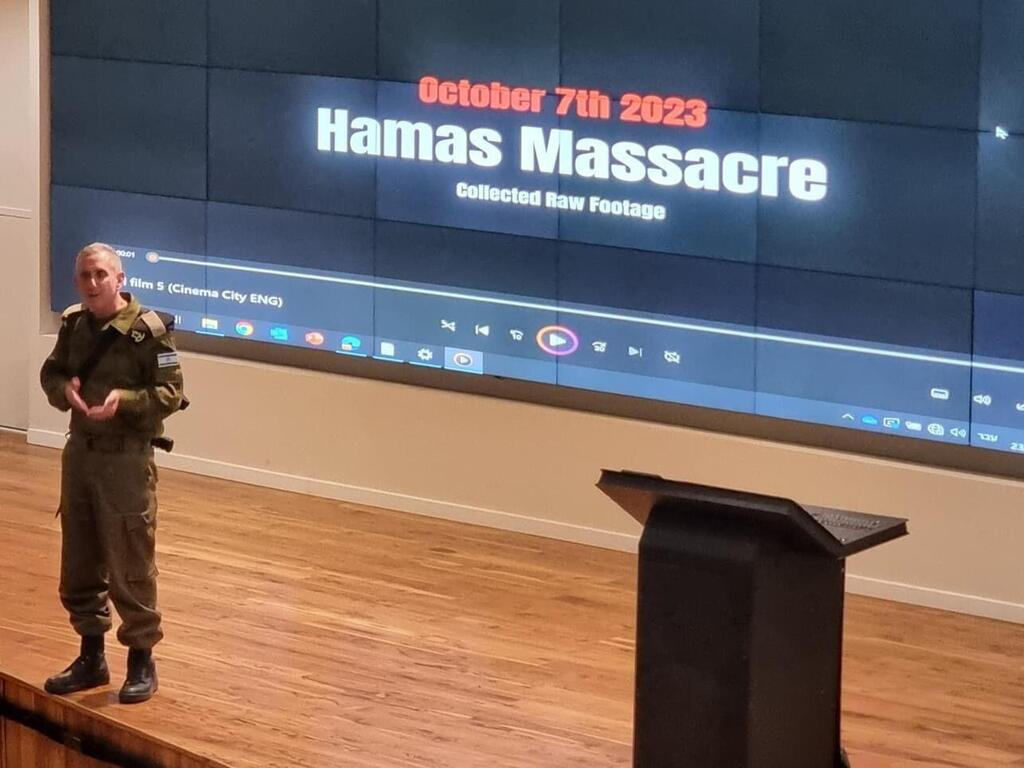

6 View gallery

IDF screens horrors to journalists from all over the world

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

The materials are incorporated in the film only after they have been 100% verified, and if they add a new event or a new angle - always at the expense of existing materials, with the intention to keep its existing length. "We didn't intend the film to be at this length, but it's long enough to tell the story and yet it's not excessively long," Harel-Fisch says.

No point in censorship

No materials are left out because of their hideousness; Everything goes, as long as it is verified. As far as Horowitz and Harel-Fisch are concerned - each of them has seen the film hundreds of times - this is a lifetime's project, which will keep on rolling in the future, for any kind of documentation and commemoration that will be done about that terrible day. "For every ten seconds in this film, you can make an entire separate 47-minutes documentary film," Harel-Fisch asserts.

Horowitz is the VP of Creative in the commercial department of Keshet Media Group Broadcasting, and Harel-Fisch was a director and editor of commercials, transitioned into high-tech, and is the brother-in-law of IDF spokesperson, Daniel Hagari. He actually conceived the idea for the film, sharing the same thoughts as Hagari's. "At the beginning of the war, I saw on the foreign networks that everyone was presenting what happened, defining it as 'supposedly'. 'Babies were 'supposedly' murdered', and so on. So, I texted Danny (Hagari), wondering why they don't show the footages I see on Telegram. I understand that there is desire to protect the families of the deceased, but why can't they delete the words 'supposedly'? why can't we present journalists with evidence behind closed doors, like in a courtroom?' Hagari called me and said, 'go for it.'"

Horowitz, a reservist in the IDF spokesperson’s unit, joined Harel-Fisch, and they worked for three consecutive days on a first version. It was immediately decided not to make any changes or manipulations in the materials, except for freeze-frames or zoom-ins here and there, "just to point to the viewers, 'Look what you see here' or 'look there', Harel-Fisch says. "The materials were very scattered, we spent most of the time collecting-sorting-verifying, and I edited it right before the first screening and sent it to Yuval and Hagari; they were the first ones to see it. We all had a recognition and understanding, when we saw everything, that this was a very significant and a life-changing event, and it took us time to recover ".

The film weaves, for the first time, a chronological story as much as possible - starting from the infiltration of the terrorists into Israel, through the indiscriminate killing spree, the capture of the prisoners and loading them onto the vehicles, through the massacre at the music festival, to the return to Gaza. "On Telegram you see very disconnected things, but when you say, 'let's put together all the murders committed in a certain place, showing the whole party, suddenly it gives you context, and the context is what gives you a story, and a story is what you lacked until that moment", Harel-Fisch explains. "And as soon as there is a story, it suddenly becomes very, very powerful. You keep making connections that you didn't have; Yuval and I look at the materials and we keep having a better understanding and insights; you suddenly see that the guy in the car is actually the guy from the reinforced mobile shelter, and the woman there who is being led away is actually the body we saw earlier laying on the floor".

What are the hardest parts for you? What stays with you and can't get out of your mind?

"For me it's primarily the voices," Horowitz says. "When there is sound, and you hear the voices of such helpless civilians, this is something that I find harder to get rid of, more than the graphic elements - and there are really horrible graphic things there, but what stays with me are the situations where people are screaming and crying and begging for help and running away, and the sound of gunfire or phones ringing when the terrorists enter people's homes while they are still in the safety room - the complete contrast between the very pastoral atmosphere in the kibbutz and the fact that cold-blooded terrorists freely roam there to slaughter them. And the most humane part of children who are caught in a situation where terrorists take over their homes."

He refers to long moments – already published in the film – documenting two children fleeing with their father to a mobile reinforced shelter into which one of the terrorists throws a grenade. The father is killed, and the children are taken, wounded, bleeding, back to the house, while the terrorist gets himself a drink from the refrigerator, and one of the children screams in despair: "Why am I alive?"

"In the end, the things that touch you the most are the places where you see yourself," Matan says. "There's a section that I didn't include at all, which for me is the most powerful, because there's a father and daughter, and she's about my daughter's age; the father is trying to protect his daughter and gets shot, and then you see her just walking away, and you don't know what happened from there on. And for me it's like the scene of the red little girl in 'Schindler's List'. It makes me shudder because it's me, I would get out of the car there and run away with her, and unfortunately I would run into the terrorist's van, and they would shoot me."

It is claimed that the film does not provide evidence of sexual assaults.

Harel-Fisch: "There is a picture of a body lying there with spread legs, draw your own conclusion from that."

The raw materials combine documentation filmed by the victims' cell phones, local surveillance cameras, but mainly through the body cameras and phones used by the terrorists for non-stop self-documentation. "It conveys their composure, their joy, the fact that they came not only to kill, but also to document, humiliate, trample and flaunt it and make a killing verification - but before that, they take out a phone to record, send and upload," Horowitz says, and Haral-Fisch adds: "The thing that people mostly talk to me about at the end of the film is the atmosphere of fun and joy among the terrorists. For them, there is a sense of celebration surrounding the whole thing."

Like a 'Clockwork Orange' effect?

"Yes. It's the same thing. You see people happy, jubilant, making whoop-whoop sounds over corpses, trampling, humiliating. There's some kind of an encounter here that I haven't seen before, between something like the college students you see in 'Spring Breakers' and murder. And these two things are combined: you see a group of people cheering and murdering".

Both Horowitz and Haral-Fisch are present at all screenings in Israel. For screenings abroad, they send a one-time link that expires after its single use. All viewers are required to deposit mobile devices at the entrance and sign a non-disclosure agreement.

Sometimes even a full screening is not required. "We were with a high-ranking official, who after a few minutes couldn't bear the sights, and seven minutes later he understood what happened and that's it - for him it was enough to get the full effect," Horowitz recalls. "He said, thank you very much, I understand, stop it, we're leaving."

6 View gallery

IDF Spokesperson Daniel Hagari speaks to foreign reports

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

The screenings can be held for large audience, or for a single person. "When I screened it to the head of the CIA, I asked him, 'Do you have children?' And he said, 'Yes, and my daughter could have been here.' He was completely shocked by the film," Harel-Fisch recalls.

Do you stay in the room during each screening?

Horowitz: "We are always inside. It is important for us to see the reactions, hear feedback, see how people experience it, in order to be more precise and improve it for the next time."

What reactions do you see inside the hall?

"People cover their face with their hands, turn their heads, feel anger and rage. Many people cry."

Harel-Fisch: "When I screened for Chris Christie (former governor of New Jersey), there was a journalist in the hall, Israeli, I think, who sat and was enraged throughout the film. 'Sss', he uttered, banging his hand on the table; he was in a fit of rage and couldn't contain himself. There are all kinds of reactions. One American told me that the closest thing he could think of was when he saw footage of shootings in schools in the U.S., but 'everything I've seen was like one shot compared to what you've been having'. And this is part of what we are trying to convey: the number of scenes and the magnitude of the event."

Horowitz: "When you finish watching and realize that what you saw is only a small percentage of what really happened, it's mind-blowing. You just saw so many crimes and horrors and hatred and mutilated bodies and a murderous killing spree - and that's nothing compared to what was there. It's inconceivable."

They continue to collect materials, immersing themselves up to their necks, refusing to think about the day after or about long-term mental damage that may be caused to them. "We are both very task-oriented, we hold screenings for many decision-makers and understand the importance of what we're doing," Harel-Fisch says. "Sometimes I come out of a very tough screening held for senior officials at the UN and UNICEF - who two days earlier, so I read, have expressed doubts about what happened - and I see how they go into the screening hall very cool-headed and come out of it broken and understanding. This fuels us to keep doing it ".

Does it impact your daily life?

Horowitz: " For me, personally, it's very difficult. I've been dealing with visuals for many years, mainly with beautiful and marketing-related things like advertisements, and suddenly we're dealing with the biggest crime committed against us since the Holocaust. I walk around with a great deal of distress and wake up every morning with a pit in my stomach about what we're doing, but I also see a great privilege in being able to come and resonate the story to people who can influence."

Harel-Fisch: "For me, it may help that I am in daily contact with the people who engage with the bodies themselves. It positions me psychologically, saying to myself that I have nothing to complain about. These people are exposed to corpses on a daily basis, compared to me; and what am I doing? - dealing with footage? We've never been exposed to these professionals who engage with death, and all of a sudden we realize that we were not alone in this, we work with a lot of amazing people dealing with it, and there is such a milieu that you can lean on and talk to and share with."

Beyond that, Horowitz says, there's no way they'll ever get used to the footages anyway. "Usually when you see things repeatedly, you gradually become indifferent to them, but here I cannot. Every time anew you witness the indescribable amount of hatred. Each time anew, I think about myself, my family and my children, I return home and the first thing I do is hug them, and every time I'm overwhelmed."

Can watching the film change the perspective of celebrities who have expressed pro-Palestinian positions, say Susan Sarandon?

Harel-Fisch: "If she had watched the film, I believe it would provide some kind of proportion to her reactions and statements. There is a factual document here with conclusive evidence of a shockingly small percentage of what happened on that day, and it cannot be contested."

I'm not sure she is disputing about what happened. Her claim and that of others, is that it should be put "in context".

Horowitz: "There are moments there that hit you in the soft belly, as a human being who just wants to live his life, and one morning they break into your home and brutally slaughter you. This is not something that should happen in humanity and in the world, and no one can deny that. I am sure that if someone like her sees the number of atrocities, they will speak differently. She may still be against us, but she will be more compassionate. She will understand."

Will there be a point where it will be necessary to show it to everyone?

"It is important to preserve the respect of the dead and the respect of the families, and to maintain our national resilience. Those who have no reason to see it - should not see it."

Two weeks ago, there was panic for fear that the film was leaked online and that all our children could be exposed to it.

"I called Matan, Matan called me, we realized that the film was still accessible only to us, on both of our computers, and that's the end of the story. We had no doubt, even for a moment, that it has leaked."

Is there frustration, knowing that you created a film which brings advocacy achievements, but you will not get credit for it?

Horowitz: "I don't want my name to be associated with this thing. Even now people refer to us as 'Matan Horrors' and 'Yuval Horrors', we don't need and don't want more than that. Each of us wants to go back to our pre-war engagements."

So why are we having this interview?

Harel-Fisch: "One of the reasons the film has a lot of impact is because people know it exists, and if this article serves this understanding, it's good to have it; and I also call on the public who has real and authentic footage, showing the horrors, to pass it on to us so that we can keep it and present it as a testimony to those who need it, while maintaining the dignity of the dead and their families."

Horowitz: "If the film had been released, it would hold interest for a day or two. Part of what keeps it relevant is that people know that there is such a horror film, and people imagine what horrors it contains, and that serves the narrative that atrocities happened - and they did happen, it is impossible to argue that - and serves our legitimacy in the world. And the longer it lasts, the better. If the film was publicly released, we would have lost momentum a long time ago."

First published: 18:55, 12.15.23